What artist Chintan Upadhyay did in Anda Cell

The Mumbai-based artist on his prison-inspired work, the power of art and how inmates turned collaborators

Artist Chintan Upadhyay at his residence in Sanpada in Navi Mumbai.

(Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)

Artist Chintan Upadhyay at his residence in Sanpada in Navi Mumbai.

(Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)After spending nearly six years in prison for the alleged murder of his estranged wife and artist Hema Upadhyay and her lawyer Haresh Bhambhani, when artist Chintan Upadhyay left Thane Central Prison on bail in September 2021, he had hundreds of artworks that needed to be transported. “It is not a cohesive body of works but my recordings, which includes sketches that could propel future works. If it wasn’t for art, I do not know what I would have done,” says Upadhyay, 49, from his Navi Mumbai home-cum-studio.

Buy Now | Our best subscription plan now has a special price

He distinctly recalls the events of December 11, 2015, when the bodies of Hema and Bhambhani were found in the northern Mumbai suburb of Kandivali. Upadhyay was in Delhi, where he had moved in 2011. Preparations were underway for his exhibition that was to be held in February 2016 in Vadodara, where Upadhyay would have unveiled two years of work with the series titled Gandi Baat, comprising caricatures of men, women and children, and addressing subjects of aggressive male gaze, abusive gestures and moral policing, among others.

With him being arrested days after the murder, the exhibition was cancelled and the artist found himself in prison. “For the initial couple of months, I was in a cell with over 400 people. It is certainly painful and difficult being there, away from friends and family. It is a tense atmosphere and there is constant fear,” says Upadhyay.

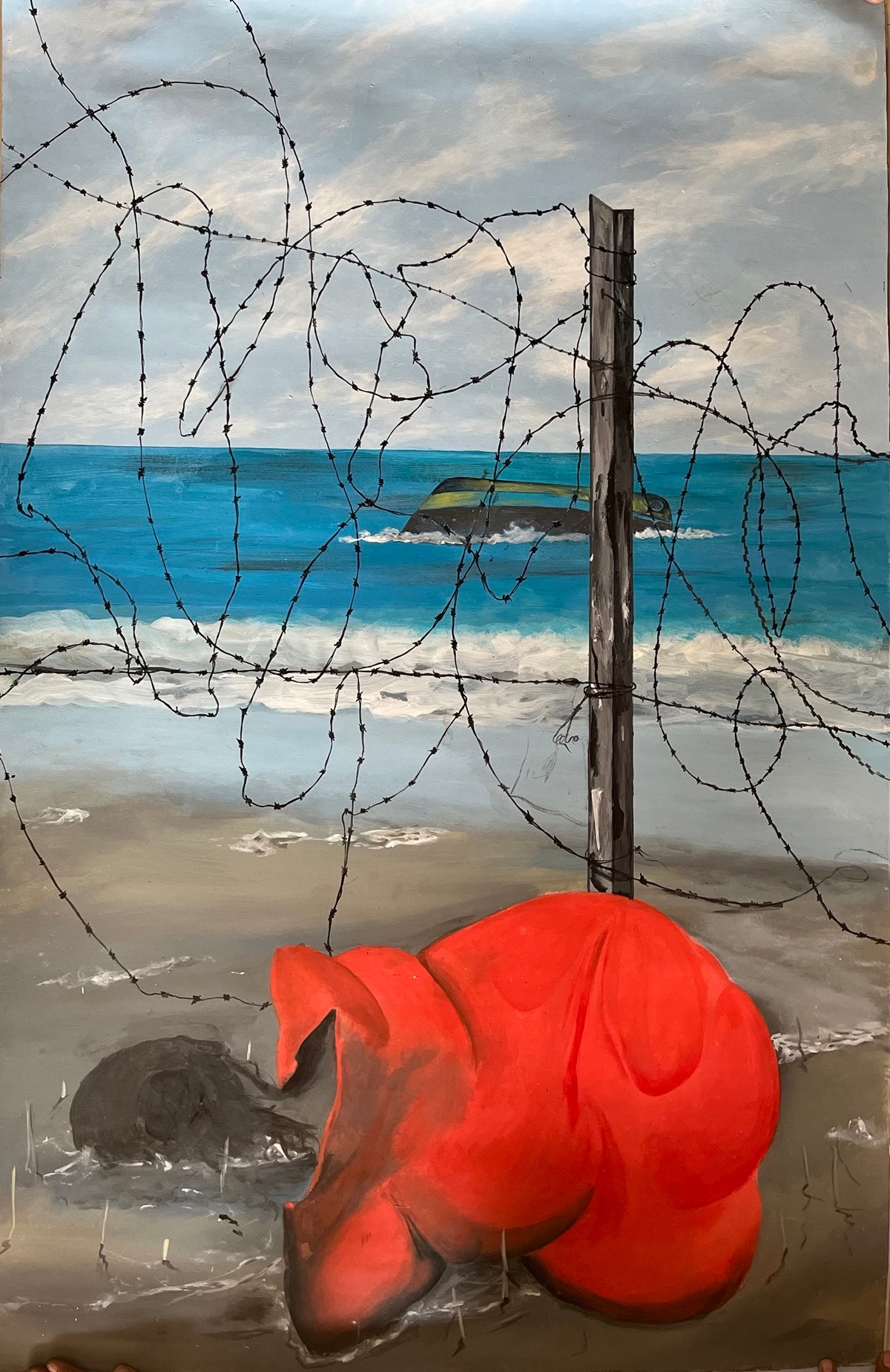

‘A dream for better life (dreamopia)’, 2017-18, acrylic on paper. (Credit: Chintan Upadhyay)

‘A dream for better life (dreamopia)’, 2017-18, acrylic on paper. (Credit: Chintan Upadhyay)

It took some prodding from the then superintendent at the prison for the artist to pick the paintbrush again, when he was requested to make preparatory drawings for a mural that depicted prison life — the scene included inmates cooking, cleaning, working in karkhanas, playing board games, volleyball and so on. Few months later, he made his first acrylic on paper in prison — a deformed elephant with elongated legs, hatching from four eggs. “I don’t remember how the painting began but perhaps the eggs were suggestive of the name of my prison cell, the Anda Cell. The elephant is struggling to find its feet and move ahead with its brittle legs that are erupting from hatched eggs. It is trying to gather strength. The work also depicts what I felt at the time,” says Upadhyay. Exhibited as part of “Art from Behind Bars” initiative (of the NGO Dagar Pathway Trust) in Mumbai in 2017, it was purchased by filmmaker Kiran Rao for Rs 4.5 lakh. “I donated the proceeds to the Prisoners’ Welfare Fund. In some ways, the sale aroused curiosity within the prison. Previously, some people had come up to me and shared that they had seen my work. Many knew about the installation at Nariman Point (City of Dream),” he says.

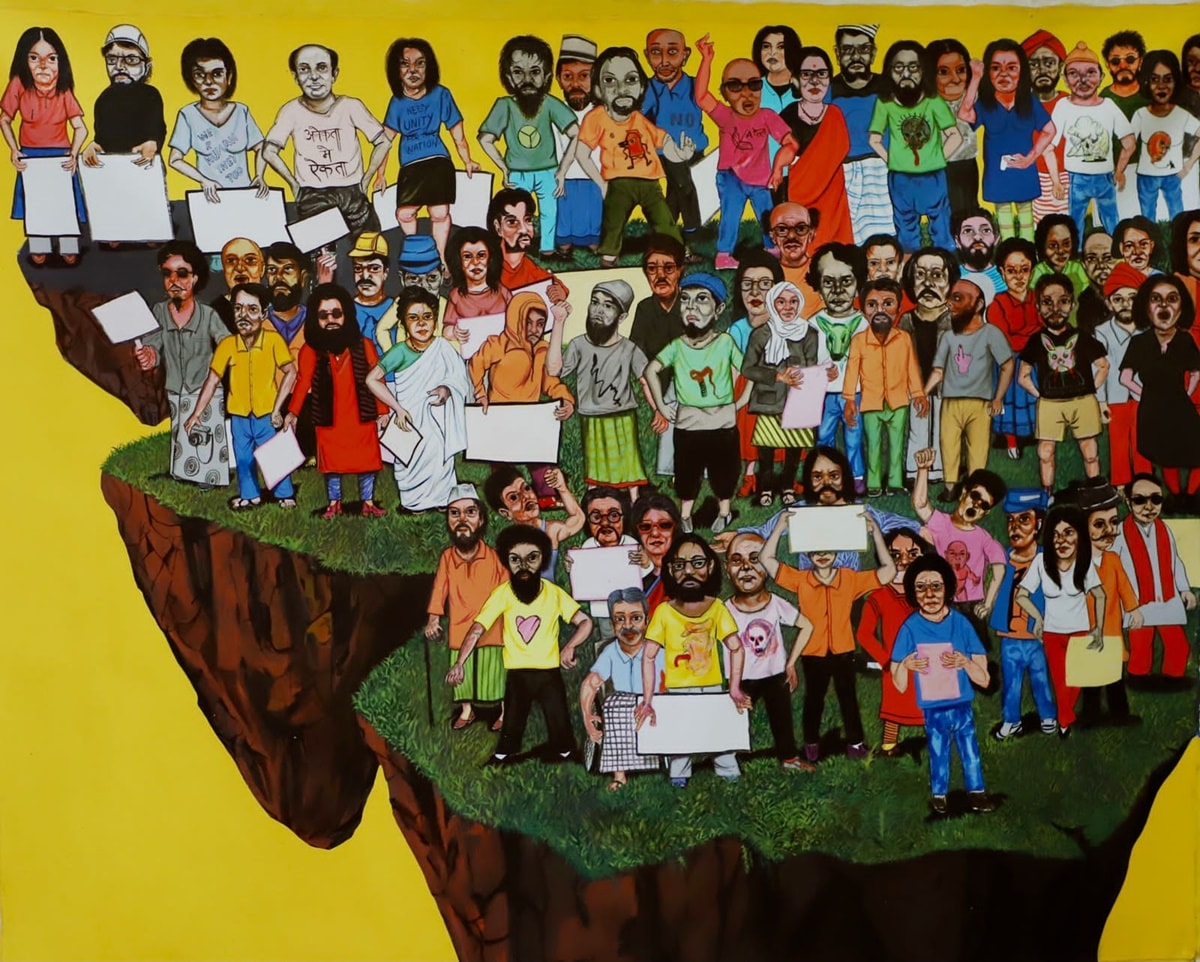

Soon, he managed to create his own work space in prison. While the jail authorities provided basic material, he could arrange for other supplies. As the audience for his art grew, he also began taking workshops, followed by regular art classes from 2019, where he imparted lessons to 25-30 students at a time. “The aim was to engage them and broaden their perspective. I would encourage them to imagine, and analyse their situation and surroundings through art. In order to build their confidence, I even let them make small interventions in my larger works,” says the artist.

Several of his students and other undertrial prisoners also became his protagonists for charcoal portraits on newspapers that he sketched during the Covid months. “At the time, it was difficult to get material and we made best use of what we had. These portraits have a deep meaning — they share the stories of these men and reflect on their varied backgrounds and ideologies,” adds Upadhyay. In the coming months, he hopes to bring almost 500 of these portraits together in a single installation, sharing common space, akin to how they lived in prison.

‘They Are Us’, a collaborative installation with the prison community. (Credit: Chintan Upadhyay)

‘They Are Us’, a collaborative installation with the prison community. (Credit: Chintan Upadhyay)

***

Son of Jaipur-based artist Vidyasagar Upadhyay, it was while pursuing his graduation in science and preparing to study architecture when Upadhyay decided to drop-out and study art. Known to astound with his works in the latter years, even in his final year showcase in 1997 at MS University, Baroda, he created a furor with his large phallus-shaped soft toys. “It was a comment on patriarchal society and preference for the male child,” says he.

It was also at MSU where Upadhyay met classmate Hema, their college romance led to marriage in 1998. The couple relocated to Mumbai soon after and their careers gradually began to flourish. Though their individual paths as artists were divergent, the two worked on multiple collaborative projects, including the 2003 exhibition “Made in China” where they turned Chemould Art Gallery in Mumbai into a museum of Chinese products available on Indian streets. By this time, the two had already gained recognition as artists of repute. In 2002, Upadhyay’s exhibition “Commemorative Stamps” at Ashish Balram Nagpal Gallery in Mumbai was applauded for depictions that represented new wealth in India. In 2005, he stunned his audience by protesting against the Gujarat riots by sitting naked as a part of the performance Baar Baar, Har Baar, Kitni Baar?, where viewers were invited to apply turmeric on his body as a gesture of compassion.

The babies that were to become his trademark were born in 2003, with the exhibition “Designer Babies”. Over the years, he modified them to adapt different sizes, mediums and hybrid forms. He painted them with varied motifs and used them to address a range of issues, such as manipulative society, female infanticide, censorship and social commodification. “These babies were designed never to grow but they did change form and evolved over time. I gave them unique identities by means of their skin, painting miniatures and manga patterns and at times even using text,” says Upadhyay.

Recognition came in the form of opportunities and commercial success. A regular at art events, his works fetched astronomical prices at international auctions. In 2007, he set a personal record when his installation New Indians was auctioned for $529,000 at a Sotheby’s auction.

A work by Chintan Upadhyay (Credit: Chintan Upadhyay)

A work by Chintan Upadhyay (Credit: Chintan Upadhyay)

***

As he unwraps his artwork made in recent years, each work reminds him of the moments in prison. He reckons it would suffice for multiple exhibitions but he does not have the bandwidth to put it together. “At the moment, I am still struggling to get into the rhythm to concentrate and work,” he says. Created over a long duration, he notes that the subjects are far-ranging — from a project Mutatis Mutandis based on Marathi writer Sanjeev Khandekar’s poems that delve into mutation, to the black-and-white stripes of the prison uniform that merge with red on 8×10 ft canvases. Stories of migrants losing lives while trying to flee war-ravaged countries led to a series of works with torrid waves on a sea shore. “There is a constant tussle between ‘us’ and ‘them’, what we don’t realise is that violence will not get humanity anywhere.”

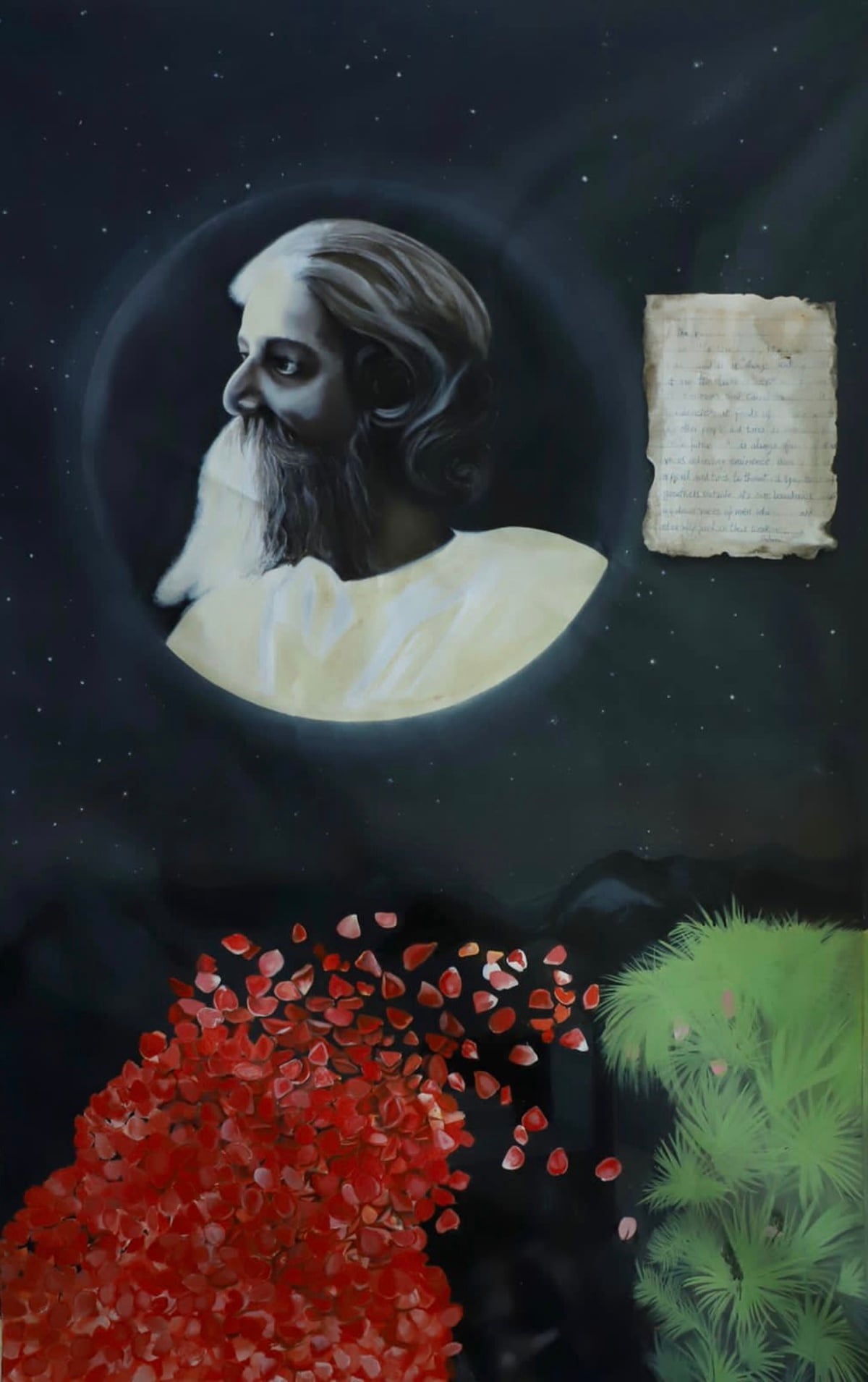

The newspapers became a window to the outside world, as he continued to respond to socio-political developments, often pasting headlines of interest in his scrapbook, which was also a visual diary where he doodled and jotted notes. When the debate on nationalism was raging in the country, Upadhyay was reading Rabindranath Tagore’s Nationalism, a compendium of lectures on nationalism by the Nobel Laureate. “I was interested in exploring how nationalism was viewed before we attained independence. I had read fragments from Tagore’s lectures and requested a friend to arrange for the book,” he says. The ensuing drawings focus on keywords from Tagore’s lectures, such as “India”, “Nation” and “Political”, and Upadhyay hopes to scan and bring them together in a composite print that would be painted over.

“Nation, national and human”, acrylic and oil on canvas, 6×4 ft. (Credit: Chintan Upadhyay)

“Nation, national and human”, acrylic and oil on canvas, 6×4 ft. (Credit: Chintan Upadhyay)

Not allowed to visit Mumbai and required to report to the local police station at the place of his residence on the first day of every month, as he adjusts to life outside prison, lending support are new friends and old. The inmates he trained in art have been contacting him to continue with the lessons. “Several of them are now out and have been reaching out to me with a desire to learn art. Some of them are now my studio assistants. Art has an ability to connect,” says Upadhyay. Meanwhile, though he has been following the work of friends, the visits to art galleries are still numbered. “I do want to see art and what everyone is making, but am still not in a frame of mind to socialise or move out a lot. It was wonderful to see art in-person and meet friends at the India Art Fair in Delhi last month, but, honestly, I was also a little lost. A lot has changed,” says the artist.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05