Sunday Long Reads: Diwali in Banaras, Rishab Shetty on Kantara’s success, celebrating Shashi Tharoor, books, and more

Here are some interesting reads from this week's issue!

Dev Deepavali on Kartik Purnima during Ganga aarti in Varanasi (Credit: Anand Singh)

Dev Deepavali on Kartik Purnima during Ganga aarti in Varanasi (Credit: Anand Singh)Why celebrating Diwali in Banaras is an experience of the city itself

Once, when shehnai maestro Ustad Bismillah Khan was asked about his routine in and affections for Varanasi — the city he’d lived in most of his life — he’d said, with a beedi between his fingers, “I roam the world, but it is Benares where my heart is… Ganga hai saamne, yahan nahayiye; iske masjid hai saamne, yahan namaz padiye; phir Balaji mandir chale gaye, vahan riyaz kiya… Ye aur kahin nahi milta (There is Ganga ahead, bathe here; there is a mosque across, read the namaz here, then one would go to Balaji temple for practice. I don’t get this anywhere else in the world).” His unconditional love for the city and its varied colours and deities surfaced in the famed Ram dhun, Tulsidas’s Raghupati raghav raja ram, manifested in the dulcet delivery on the shehnai. It also had within its gentle notes an understanding that while Varanasi’s ghats and gullies, music and food made space for religion, it was never entrenched in rigidity.

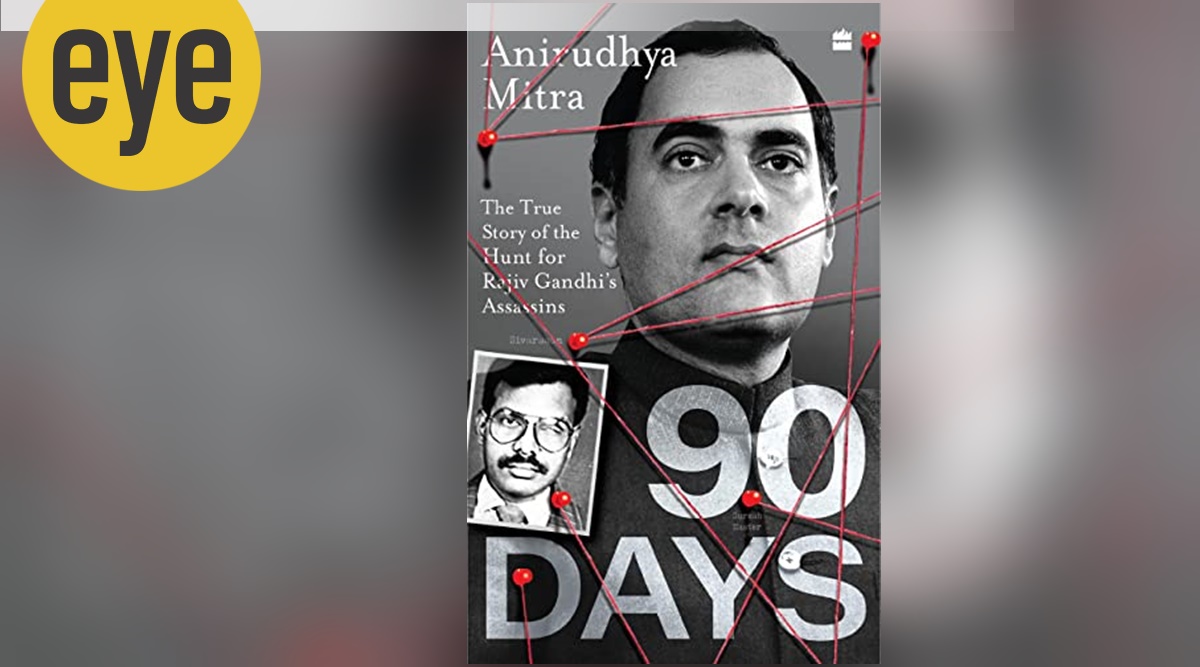

Ninety Days: The True Story of the Hunt for Rajiv Gandhi’s Assassins is a taut reconstruction of a political assassination that shook India

Ninety Days: The True Story of the Hunt for Rajiv Gandhi’s Assassins; by Anirudhya Mitra; Harper Collins; 284 pages; Rs 599 (Photo: Amazon.in)

Ninety Days: The True Story of the Hunt for Rajiv Gandhi’s Assassins; by Anirudhya Mitra; Harper Collins; 284 pages; Rs 599 (Photo: Amazon.in)

This is a step-by-step account of the investigation of one of the most shocking crimes in contemporary India. Undeterred even by the cold-blooded threats from the LTTE, the author, then a principal correspondent with India Today magazine, fully utilised his contacts in the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and the Intelligence Bureau to expose the conspiracy behind the killing of former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, along with 18 others, in a political function at Sriperumbudur, Tamil Nadu. The book is a vivid revelation of the work done by the CBI’s Special Investigation Team (SIT), despite facing hurdles and harassment at times.

Why the idea to convert protected areas like the Aravallis into safari parks is a recipe for disaster

These days the trend is to rewild wastelands to bring them back as close as possible to nature. (Credit: Ranjit Lal)

These days the trend is to rewild wastelands to bring them back as close as possible to nature. (Credit: Ranjit Lal)

All over the world these days, the trend is to “rewild” wilderness and wasteland areas, to bring them back as close as possible to their original state of nature. This has happened with some success in the US and in Europe – where nearly every wild area was manicured and pedicured and planted with trees all standing stiffly to attention in plantations, which were regularly “harvested” and “managed” (as if Mother Nature was inept at her job.) Now they’re letting Mother Nature take down her hair again; wear it wild all over her face, and take over what she’s best at doing: keeping the world ticking over.

Shashi Tharoor: celebrating the man and his words

Shashi Tharoor stands on the side of the individual, of justice for all, of legislating with heart and vision to bring self-respect for all citizens (Credit: Suvir Saran)

Shashi Tharoor stands on the side of the individual, of justice for all, of legislating with heart and vision to bring self-respect for all citizens (Credit: Suvir Saran)

In the perennial tension between communitarian privilege and individual rights, Ambedkar stood squarely on the side of the individual,” writes Shashi Tharoor in Ambedkar: A Life (Aleph, 2022), which has recently made it into bookstores, “In the battle between timeless traditions and modern conceptions of social justice, Ambedkar tilted the scales decisively toward the latter. In the contestation between the wielders of power and the drafters of law, Ambedkar carved a triumphant place for enabling change through democracy and legislation. In a fractured and divided Hindu society he gave the Dalits a sense of collective pride and individual self-respect. In so doing, he transformed the lives of millions yet unborn, heaving an ancient civilization into the modern era through the force of his intellect and the power of his pen.” Winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award, as well as numerous other accolades for his writings, Shashi could easily be the man for whom another in history would write these words.

What makes Rishab Shetty’s Kantara one of the highest-grossing Kannada films of all time

Rishab Shetty in a still from Kantara.

Rishab Shetty in a still from Kantara.

THE phenomenal success of the Kannada movie Kantara, a big-screen spectacle which is a masterly mix of myth, folklore, drama and action, has reiterated the authenticity and appeal of stories rooted in our cultural milieu. If Rishab Shetty, 39, its writer, director and lead actor, is to be believed, the script was written in five months, was made at a frenzied pace without sparing much thought for its possible box-office fate.

How Diwali became a festival of food and memories, history and culture

Batashe comes in a variety of shapes and colours; Credit: Anand Singh

Batashe comes in a variety of shapes and colours; Credit: Anand Singh

There was a time when diyas were in the spotlight, rangolis were drawn on thresholds and greeting cards were handmade. Food, prepared at home, was shared among neighbours and relatives, and we walked in and out of homes unannounced. Even today, there are festivals that cut across religions and regions. These include Eid, Diwali and Christmas. Markets are dressed up like newly-wedded brides and homes are lit with many time-honoured traditions.

Rashmee Roshan Lall traces the American experiment in Afghanistan in her novel ‘The Pomegranate Peace’

Book cover of ‘The Pomegranate Peace’ by Rashmee Roshan Lall (Source: Amazon.in)

Book cover of ‘The Pomegranate Peace’ by Rashmee Roshan Lall (Source: Amazon.in)

The book is set in Afghanistan, but only notionally. Actually, it’s “Ameristan”, as Rashmee Roshan Lall, author of The Pomegranate Peace, calls the US Embassy complex in Kabul, “which is as far from Afghanistan mentally as possible”.

‘I have always been cautious’: Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka

Shehan Karunatilaka. (Credit: Penguin Random House India)

Shehan Karunatilaka. (Credit: Penguin Random House India)

Even though the time he gets to spend with his guitar is now decidedly less, Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka, 47, has lost none of his rockstar grunge. The black nail paint on his fingers — “male polish”, he calls it — was a hat tip to his “juvenile rockstar ambitions”. “My wife took me for a manicure before the award ceremony. She said you are going to the Booker, you need to look nice. Big mistake! I was getting the manicure and I see all these bottles and I told the manicurist, ‘Can you put something black?’ and here we are!” he says, with a laugh. His phone hasn’t stopped buzzing since the time he became the second writer from Sri Lanka to win the Booker Prize for his novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida earlier this week. “We won the Asia Cup (cricket tournament) but we haven’t had many victories in Sri Lanka in the last year,” he says. In this interview, the Colombo-based writer speaks of his literary influences and why the novel went through a rigorous round of re-editing. Edited excerpts:

In defence of Daniel Ladinsky and his complicated legacy of paying homage to Hafiz

The Gift: Poems by Hafiz the Great Sufi Master

The Gift: Poems by Hafiz the Great Sufi MasterDaniel Ladinsky

Penguin Books

352 pages

Rs 1,199

(Source: Amazon.in)

‘A poet is someone/ who can pour light into a cup,/ then raise it to nourish/ your beautiful, parched, holy mouth.’

When I first read these lines in Daniel Ladinsky’s renditions of the poet Hafiz, I remember the hush that fell upon my world. There was the sense of having stumbled upon the right table at the dinner party (or the tavern, which is Hafiz’s preferred habitat), and the added delight of being seated exactly beside the right company. Who was this poet? How did he put word to experience with such immaculate precision? How did he speak so directly from the cave of one heart to another, making the hiatus of centuries so utterly irrelevant?

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05