Opinion Yakub Abdul Razak Memon shouldn’t have been hanged

It may be too late for Yakub Memon. But it is time for India to rethink the use of the death penalty.

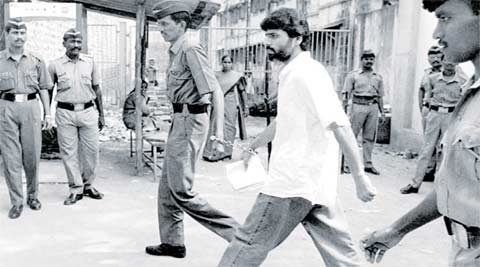

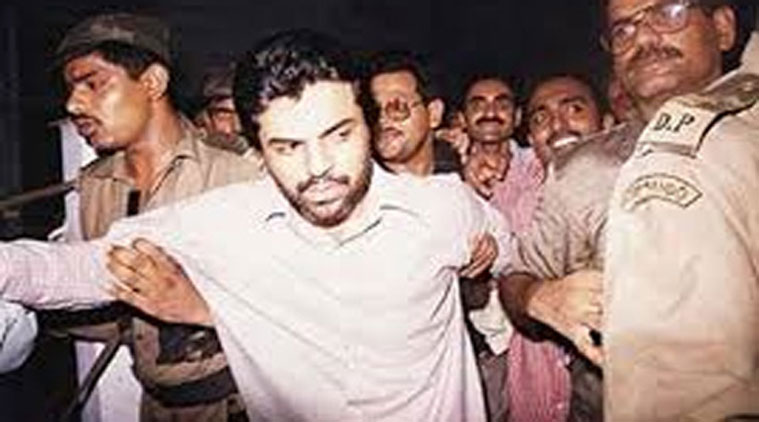

yakub Memon

yakub Memon

This morning, Yakub Abdul Razak Memon was hanged. For many, the execution of a man convicted for the killing of 257 people will be a reason to celebrate. It ought not to be. India’s use of the death penalty demeans that most cherished idea on which our republic rests, the idea of justice. The execution of Memon must compel us to question our most fundamental beliefs. The wounds inflicted on March 12, 1993, can be healed only by justice — but what the hangman offers is only a crude approximation of that cherished ideal, the bedrock of our life as a republic and as a people.

[related-post]

Leave aside high moral or spiritual principles. The decision to execute rests on caprice. For one, former judges like Ajit Shah have argued that the Supreme Court has applied inconsistent criteria in its delivery of the death sentence, and often erred in its understanding of precedent. Even the judges who heard Memon’s clemency appeal, after all, were divided on whether he deserved it. Then, judges’ understanding of what constitutes a death penalty crime has varied widely. Rabindra Pal, who burned alive Graham Staines and his two infant sons, was, for example, given a life sentence after judges held that the missionary’s proselytising was itself a mitigating circumstance. Bias also stains the dispensation of the death penalty: of 385 prisoners handed the sentence between June 2013 and January 2015, three quarters belonged to economically or socially vulnerable communities.

The great philosopher Moshe ben Maimon argued that to execute anyone on less than complete certainty of their guilt would reduce justice “to the judge’s caprice”. That caprice is precisely what the death penalty is, everywhere it is in effect. In the United States, over 145 people sentenced to death since 1939 have been released after new evidence emerged of their innocence. The tide of acquittals of prisoners on death row has swelled as genetic science improves. Nor does the death penalty serve any social purpose, beyond vengeance. The United States’ National Academy of Sciences, in the most thoroughgoing meta-study to date, has shown there is no correlation between the death penalty and violent crime. Israel — beset, like India, by terrorism — hasn’t executed anyone since 1962. Its first application of the sentence was in the case of Meir Tobianski, a soldier executed on treason charges in 1948 — and established, a year later, to have been innocent. Though the US and China retain the death penalty, the global trend is 58 for to 140 against. Today is the right day for India to honour the liberal heritage on which great nations are built, and take a step towards joining the right side of this divide.