Opinion Why Pakistani artists should condemn terror attacks in India

An artist represents freedom — the universal, unalienable idea that humanity must be free to live without fear, violence and misery.

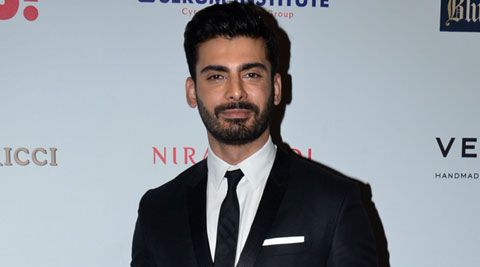

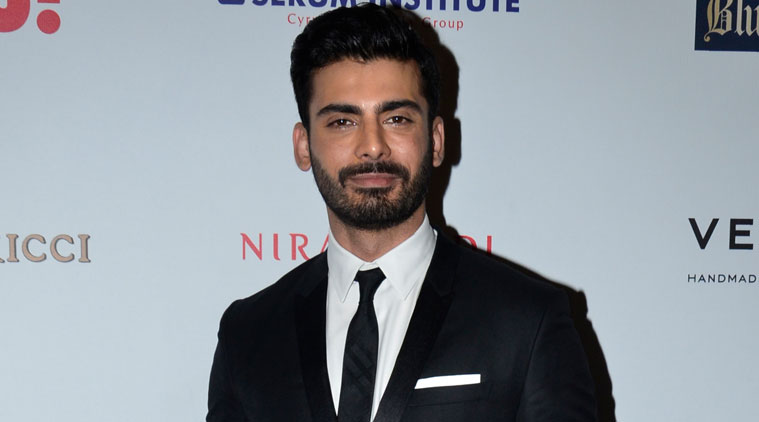

No one appreciates Pakistani artist Fawad Khan’s mind-blowing stubble more than I, but an artist is more than a mimic. (Source: File)

No one appreciates Pakistani artist Fawad Khan’s mind-blowing stubble more than I, but an artist is more than a mimic. (Source: File)

Art, declared political and artistic voices recently amidst the din over banning Pakistani artists from Indian films, should be above politics. But nothing could be more impossible for art is dipped deeply in politics. Every stroke of a brush, every word from a pen, how a girl says yes or no in a film, is tangibly touched by the politics of its time. Colonial politics fuelled Bankim Chandra and Rabindranath Tagore’s art, daring to imagine a land where Indians could hold their head high. The politics of independent India, its black market, its poverty, its passion for dignity, informed the ‘‘angry young man” embodied by Amitabh Bachchan in the 1970s. And since liberalisation, global to local politics shape Indian art, from Karan Johar’s shiny movies to gritty outpourings like Dalit rap. To imagine art is above politics isn’t imagining art — it’s imagining a plastic product, bereft of the passions, the ideas, the violence and dreams of our times.

Similarly, imagining artists need not have a political stand is belittling artists. An artist isn’t a pretty party performer. An artist should entertain, of course — and no one appreciates Pakistani artist Fawad Khan’s mind-blowing stubble more than I. But an artist is more than a mimic. An artist represents freedom — the universal, unalienable idea that humanity must be free to live without fear, violence and misery. In this context, the desire to see Pakistani artists, appreciated in India, condemn the Uri attack, isn’t unreasonable. It’s logical for Uri was a cowardly and brutish assault upon those who had no opportunity to defend themselves. Any artist would want to throw in their colours, their songs with those who fight such darkness — and against those who want to crush the joy, the energy, all that jazz of the free world.

History shows the opprobrium earned by artists who differentiate between human lives. Richard Wagner was a great

composer. But his association with Germany’s Nazi ideology shrank his stature, making it

hard for many who love Wagner’s Ring to not think, when it plays, of the millions herded into Holocaust camps, far

from wine, cheese, sonatas and philosophies. Some artists have lived within inhuman states, challenging them courageously. Through South Africa’s Apartheid, Nadine Gordimer shed light on darkness with heart-breaking, heart-warming words, even as the civilised world refused to play ball with a system that believed skin colour should determine a human’s life.

Terrorism also affronts people everywhere and all artists saying so makes sense. Previously, Pakistani artists condemned terror attacks in Peshawar and Paris. Their silence on terror hurting India thereby looks stark — and draws attention to their being Pakistani, rather than artists, which is a loss. Once, Faiz challenged the authorities of Pakistan, his irony leading him to the iron doors of Karachi jail. But that was an artist’s work — creating courage against violence by composing beautiful words and living them. By condemning terror in India, Fawad Khan and company could emphasise they’re not just Pakistan’s beautiful people, sprinking shers and sherwanis on routes perfumed with attar — and dynamite.

Yet, arguing art is above politics presents theorists with the opportunity to support lifting The Satanic Verses ban. In 1988, on this day, Salman Rushdie’s book was banned from import in India, a Congress government flirting with Muslim and Hindu right-wings, pulling Ayodhya, pushing Shah Bano into a cynical conjurer’s hat. But its Rushdie ban stamped hard on further art, M.F. Husain then hounded for drawing Hindu goddesses, Rohinton Mistry for discussing the Shiv Sena. Today, if art’s suddenly above politics, those arguing this should demand The Satanic Verses be free in India, to provoke and outrage, awe or bore, do what art does — help us develop the ability to say, “I hate this”, but not with a bomb.

The point of art is to shake, even break your heart and patch it up again, through paintings, words and chords that celebrate your life — and your right to live it, no matter who you are. Any art that doesn’t stand for that is just a thumka in the annals of time.

(This article first appeared in the print edition under the headline ‘For Their Art’s Sake’)