Building block: Peace in the museum dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi

The Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya or the Gandhi Museum, within this 36-acre land, houses over 30,000 letters written by and to Gandhi, photos, and documents, including those edited by his secretary Mahadev Desai.

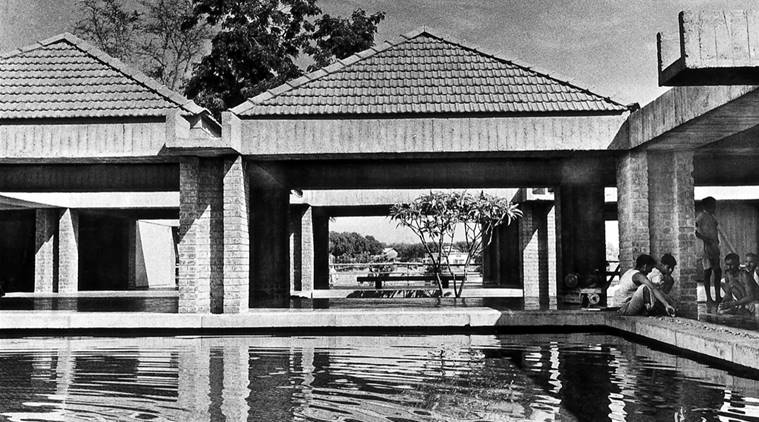

An oasis of calm: The Gandhi Museum in Ahmedabad.

An oasis of calm: The Gandhi Museum in Ahmedabad.

Mahatma gandhi’s words, “I want the cultures of all the land to blow about my house as freely as possible,” ring true as one walks into the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad.

Gandhi and Kasturba lived here by the banks of the river for over a decade. With ample space to greet visitors, the ashram has many doors and windows that are literally open to the winds of change. The ashram became the vortex of civil disobedience, where ideas of khadi and non-cooperation grew stronger. Gandhi led the salt satyagraha from this ashram along the Sabarmati in 1930. His kutir and the adjoining cottages for workers and guests are a reminder of the modesty and sensitivity that governed his life. The tiled roofs, the brick walls, the stone floor and the wooden doors find resonance in the museum dedicated to the Father of the Nation. The ashram completed 100 years last year.

The Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya or the Gandhi Museum, within this 36-acre land, houses over 30,000 letters written by and to Gandhi, photos, and documents, including those edited by his secretary Mahadev Desai. This museum would go on to be architect Charles Correa’s first major public project, commissioned by the Gandhi Smarak Trust in 1958. At its inauguration on May 10, 1963, Nehru commended Correa for the structure’s lack of pretensions and simplicity of the space — which, for the prime minister, was holy ground.

Correa was mindful of Hungarian designer Gyorgy Kepes’ philosophy, that for a museum one needed places for the “eyes to rest and the mind to contemplate”. Therefore, Correa used courtyards at the museum to provide relief, peppered with display areas and pathways that lead to a central waterbody. Keeping the form pure, with hollowed cubes of 6×6 m, he evoked the image of village streets, dear to Gandhi’s heart. Correa shunned glass and kept the window with wooden louvres to modulate light into the museum areas.

Light and air move freely through the 51 modular units of the museum. In Rebecca Brown’s book, Art for a Modern India, Brown highlights the segmental approach to building centres as an element of Indian culture. “One steps out of the box to find oneself in a verandah, from which one moves into a courtyard — and then under a tree, and beyond onto a terrace covered by a bamboo pergola, and then perhaps back into the room and onto a balcony”. These informal entries and exits amplify at the museum, where spaces flow into one another.

Correa has made the museum as a living structure that can expand and evolve over time. Even though Gandhi’s Salt March began at the ashram, the streets across the country were swelling up with his followers. The museum stands as a witness to that pattern of growth where, with time, there is scope to make room for more programmes and expansions.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05