Last week, the Reserve Bank of India released its annual study of state-level budgets. With each passing year, understanding about state government finances is becoming more and more important. That’s because of two broad reasons.

One, states now spend one-and-a-half times more than the Union government and, in doing so, they employ five times more people than the Centre. What these two trends mean is that not only do states have a greater role to play in determining India’s GDP than the Centre, they are also the bigger employment generators. As such, it is crucial to understand their spending pattern. If, for example, their combined expenditure contracts from one year to the other, then it will bring down India’s GDP.

Two, since 2014-15, states have increasingly borrowed money from the market — a trend captured in the fiscal deficit figure. In fact, their total borrowing almost rivals the borrowing by the Union government. This trend, too, has serious implications on the interest rates charged in the economy, the availability of funds for businesses to invest in new factories, and the ability of the private sector to employ new labour.

Why fiscal deficit matters

Suppose there is only Rs 100 in the economy that is available in the form of investible savings. This money could be borrowed either by private businesses (to invest in a new or existing venture) or by the government (to make roads, pay salaries etc.). Suppose again that initially, businesses borrow Rs 50 and the central government borrows Rs 50. If, however, state governments also start borrowing, say Rs 20, then private businesses will have only Rs 30 left to borrow and invest. Worse, this Rs 30 would come at a higher interest rate because the same number of people would be now vying for less money. That is why economy observers and businesses fuss over the fiscal deficit number the most.

There is another reason why states borrowing more and more should raise concerns especially when they borrow to meet unexpected policy goals such as farm loan waivers. Each year’s borrowing (or deficit) adds to the total debt. Paying back this debt depends on a state’s ability to raise revenues. If a state, or all the states in aggregate, find it difficult to raise revenues, a rising mountain of debt — captured in the debt-to-GDP ratio — could start a vicious cycle wherein states end up paying more and more towards interest payments instead of spending their revenues on creating new assets that provide better education, health and welfare for their residents.

In short, with each passing year, state government finances have become more and more important not only for India’s GDP growth and job creation but also for its macroeconomic stability. That is why, the 14th Finance Commission had mandated prudent levels of both fiscal deficit (3% of state GDP) and debt-to-GDP (25%) that must not be breached.

What RBI found

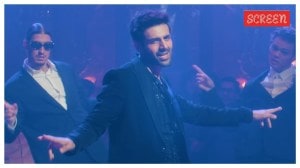

The first thing of note that the RBI report has found is that, except during 2016-17, state governments have regularly met their fiscal deficit target of 3% of GDP (see Chart 3). On the face of it, this should allay a lot of apprehensions about state-level finances, especially in the wake of extensive farm loan waivers that many states announced as well as the extra burden that was put on state budgets after the UDAY scheme for the power sector was introduced in 2014-15. Under UDAY, state governments had to take over the debts of power distribution companies (discoms).

Story continues below this ad

However, any relief on the fiscal deficit front is of limited value because most states ended up meeting the fiscal deficit target not by increasing their revenues but by reducing their expenditure and increasingly borrowing from the market.

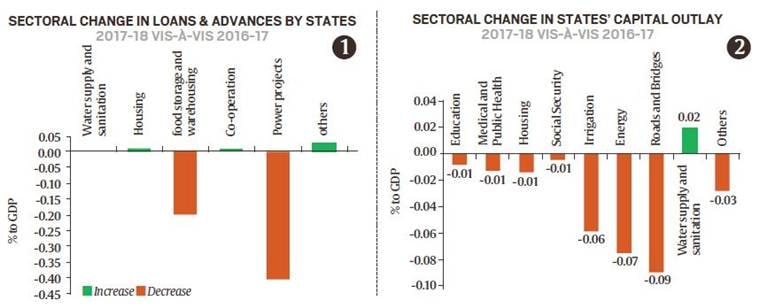

Nothing brings this out better than what happened in 2017-18. As one can see from Chart 1, fiscal deficit for all states had breached the 3% (of GDP) mark in 2016-17. But in the very next year, states reduced the fiscal deficit by 109 basis points and brought it down to just 2.4%. But the bulk of this cut was achieved by cutting expenditure — and that too capital expenditure, which was cut by 86 basis points.

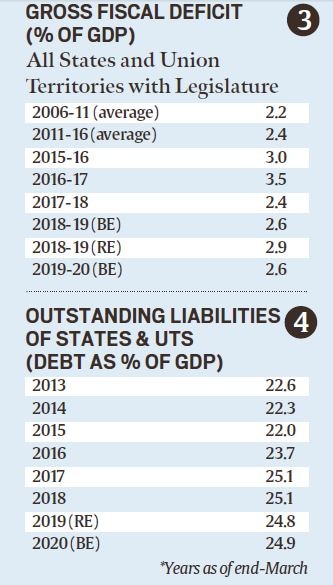

But this cut had a flip side. It adversely affected (Chart 1) the loans that state governments provided to power projects, food storage and warehousing. It also hurt (Chart 2) the states’ capital budget allocation for key social and infrastructure sectors.

Impact on national economy

The RBI’s report states that this reduction in overall size of state budgets likely worsened the economic slowdown that was slowly setting in since the start of 2016-17, when India had grown by 8.2%. “… There has been a reduction in the overall size of the state budget in 2017-19. This retarding fiscal impulse … has coincided with a cyclical downswing in domestic economic activity and may have inadvertently deepened it,” it states. It is noteworthy that 2017-18 saw India’s GDP growth rate decline to 7.2% and it has been declining since.

Story continues below this ad

Possibly the most worrisome observation by the RBI is that while states have met their fiscal deficits, the overall level of debt-to-GDP (Chart 4) has reached the 25% of GDP prudential mark. “A slightly stringent criterion as prescribed by the FRBM Review Committee and in line with the revised FRBM implied debt target of 20 per cent will put most of the states above the threshold,” warns the RBI.

The trouble is states have found it difficult to raise revenues. As the report explains, “States’ revenue prospects are confronted with low tax buoyancies, shrinking revenue autonomy under the GST framework and unpredictability associated with transfers of IGST and grants. Unrealistic revenue forecasts in budget estimates thereby leave no option for states than expenditure compression in even the most productive and employment-generating heads.”

Two, since 2014-15, states have increasingly borrowed money from the market — a trend captured in the fiscal deficit figure.

Two, since 2014-15, states have increasingly borrowed money from the market — a trend captured in the fiscal deficit figure.