On Monday (October 13), the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2025” — popularly called the Nobel prize for economics — to Joel Mokyr (Northwestern University, US), Philippe Aghion (Collège de France, INSEAD, and LSE) and Peter Howitt (Brown University, US) “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth”.

On the face of it, this was an odd pairing to share the award. Mokyr, an economic historian, has received the Nobel for his work that was grounded in using historical sources to uncover the causes of sustained economic growth in the world. Whereas, Aghion & Howitt have been recognised for their mathematical model, which instead of looking into the past, analysed how individual decisions and conflicting interests at the level of firms can lead to steady economic growth at the national level.

The commonality, however, lay in their ability to explain why humans have managed to achieve sustained economic growth over the past two centuries when for most of human history economic stagnation was the norm.

Mokyr’s contribution

These days there is hardly a debate, political or otherwise, that does not reference a country’s economic growth. A fast GDP growth rate is considered to be a necessary ingredient for anyone to justify being in power or for any argument to carry weight. Countries such as China and India have grown at more than 7% for decades now, pulling millions out of abject poverty.

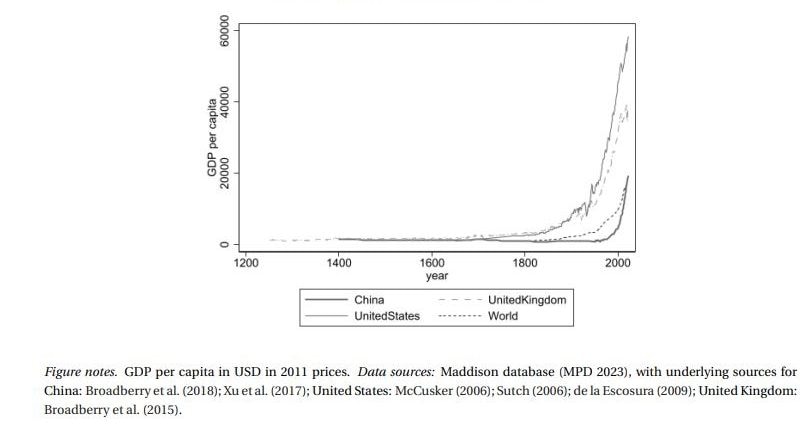

However, fast economic growth of this kind has not only been absent for most of human history, in fact, it has been unheard of. As CHART 1 shows, the norm has been economic stagnation and, here is the crucial point, this stagnation happened despite technological advancements.

GDP per capita over history. (Nobel website)

GDP per capita over history. (Nobel website)

So, what changed over the past 200 years that sustained economic growth became the new normal?

Story continues below this ad

Through his historical research, Mokyr showed that prior to the Industrial Revolution, technological innovation was primarily based on “prescriptive” knowledge. That is, people often knew “how” things worked but they did not have the answer to “why” things worked (which is the part Mokyr calls “propositional” knowledge).

But this changed over the 16th and 17th centuries as the world witnessed the Scientific Revolution as part of the Enlightenment. According to Mokyr, scientists began to insist upon precise measurement methods, controlled experiments, and that results should be reproducible. This led to the “how” and “why” queries getting answered to produce “useful” knowledge.

For instance, the steam engine was improved thanks to contemporaneous insights into atmospheric pressure and vacuums, and advances in steel production due to the understanding of how oxygen reduces the carbon content of molten pig iron.

But this confluence of “how” and “why” of technological change was not enough, according to Mokyr, to propel the world on the path of sustained economic growth. The last piece of the puzzle as it were was the society’s openness to change, another key attribute of the Enlightenment.

Story continues below this ad

Growth from technological change produces both winners and losers. Unless a society is willing to accept this process of “creative destruction”, a term first used by economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1942, change will not happen. Mokyr found that this was a critical difference and showed in different ways from the create of institutions such as the British parliament (which essentially curtailed the privileges of the aristocracy) to the defeat of the Luddite movement (workers in early 19th century who resisted the use of machines).

Aghion & Howitt’s contribution

Aghion & Howitt tackled the same question or phenomenon — how technological advancement leads to sustained growth — but their approach was very different. Instead of looking back into the past, they studied the modern economy and found that under the calm waters of stable economic growth at the national level, lay a lot of upheaval at the firm level.

As shown in CHART 2, in the US, for example, over ten per cent of all companies go out of business every year, and just as many are started. Among the remaining businesses, a large number of jobs are created or disappear every year. While these numbers may vary, the pattern of economic growth is the same in other economies as well.

Dynamism in the US. (Nobel website)

Dynamism in the US. (Nobel website)

Through a mathematical model (framework) presented in the shape of a paper in 1992, Aghion & Howitt showed how this kind of creative destruction, while looking massively upsetting at the level of an individual company, could lay the foundations for stable macroeconomic growth.

Story continues below this ad

Here’s a brief: Imagine an economy where the rules are such that companies with the best technology can take out patents on their products. The protection from patents can create a monopoly that creates profits and pays for the production costs. However, a patent offers protection from competition, but not from another company making a new patentable innovation. This creates an incentive for others to compete and out-innovate in bid to create monopolies and profits.

However, money for investment in R&D of companies originates in households’ savings. How much households save, in turn, depends on the interest rate. That, in turn, is affected by the growth rate of the economy. As such, production, R&D, the financial markets and household savings are therefore linked and cannot be analysed in isolation. Aghion & Howitt’s was the first macroeconomic model for creative destruction to have “general equilibrium” — that is, when all these different markets are in balance.

Policy implications

The work of the newly minted Nobel laureates lies at the heart of many of the burning debates at present. Should governments subsidise R&D in companies? Would that help the society or the company or the company that out-innovates the first company? Another, if not an alternative question is, whether governments should subsidise social welfare and create a social safety net to ensure the society does not lose its openness to change.

GDP per capita over history. (Nobel website)

GDP per capita over history. (Nobel website) Dynamism in the US. (Nobel website)

Dynamism in the US. (Nobel website)