© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

These murals were painted after independence with a view to indigenise the ambience of the Rashtrapati Bhavan. (Source: Rashtrapati Bhavan Archives)

These murals were painted after independence with a view to indigenise the ambience of the Rashtrapati Bhavan. (Source: Rashtrapati Bhavan Archives)The transformation of the Viceroy’s House into the Rashtrapati Bhavan was a leap from imperialism to nationalism in which the visual art played a major part. The pervasive influence of Swami Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore impacted the world of art, too. It swept across the Rashtrapati Bhavan, and as far as the Vatican and the personal collection of the Mountbattens at Broadlands, Hampshire. Paintings of Sukumar Bose, of the Bengal School of art, adorn the walls at the Rashtrapati Bhavan and the house of the Mountbattens. In 1950, Pope Pius XII commissioned Bose, then art curator at the Rashtrapati Bhavan, to create a painting in Indian style on a Christian theme. Titled The Nativity – The Birth of Christ, the painting was at the Vatican and now it appears to be in a private collection.

Margaret Noble, the Irish lady, who became the most famous disciple of Swami Vivekanand and was given the name Sister Nivedita, was a mentor to the early painters of the Bengal School. Well before her demise in 1911, she had anticipated that “mural painting in India will have three different subjects – the national ideals, the national history, and the national life.”

Painters from the Bengal School such as Abanindranath Tagore, Asit Kumar Haldar, Lalit Mohan Sen and Bose greatly benefitted from her teachings. Bose created great works of art depicting Indian themes.

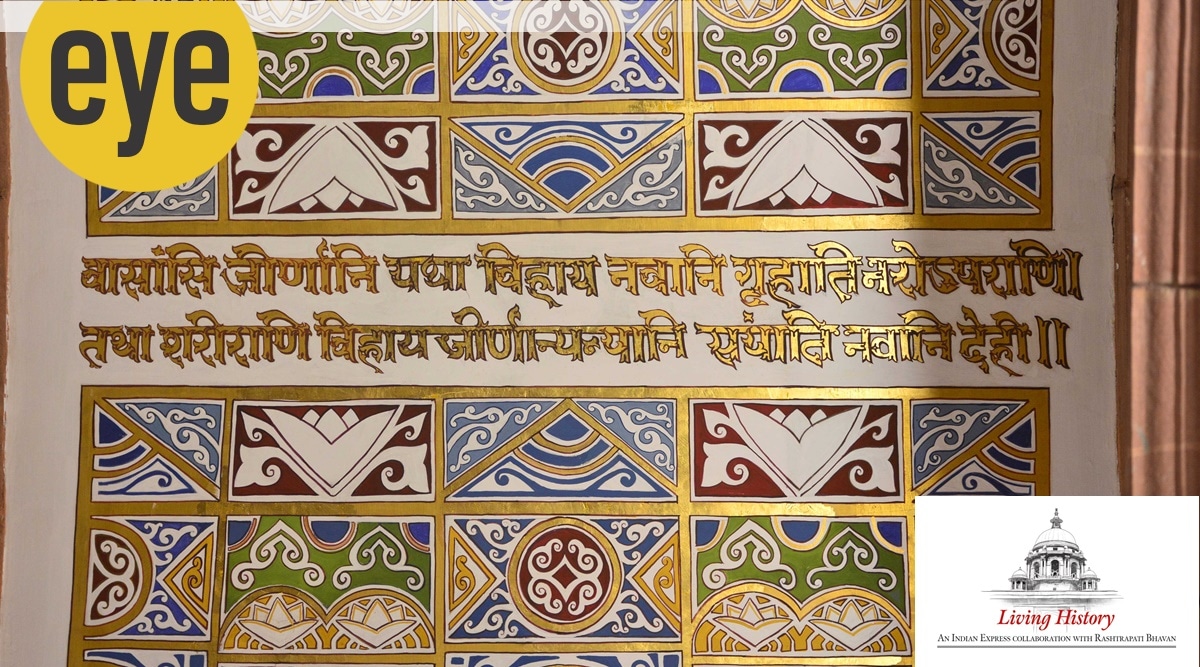

With gold leaf accents, the murals are a feast of diverse styles of Indian art. (Source: Rashtrapati Bhavan Archives)

With gold leaf accents, the murals are a feast of diverse styles of Indian art. (Source: Rashtrapati Bhavan Archives)

A walk through the state corridor of the Rashtrapati Bhavan is evidence of Sister Nivedita’s prescient observations. If one were a visitor of the President, you would be led down the state corridor, a short 75m stretch, before you reach his study. En route, you would see the finest expressions of India’s culture through decorative murals on the vaulted ceilings of the corridor and along its walls.

These murals were painted after independence with a view to indigenise the ambience of the Rashtrapati Bhavan. They are a feast of diverse styles of Indian art, painted in exquisite cohesion. Experts have described this approach to art as an expression of cultural nationalism.

From Harappan seals depicting bulls; motifs from the Thangka style of Tibetan paintings; Buddhist paintings of Ajanta; the alponas of Bengal, and the sacred mandalas that represent the cosmos, figures of lotuses, conch shells, flowers and peacocks have been painted with perfect symmetry and precision. The Indian aesthetics of Satyam-Shivam-Sundaram (Truth, Goodness and Beauty) are reflected in the state corridor, too. As one enters this space, the viewer experiences positive energy and peace all at once. An Indian artist’s dharma is a joyous exploration of truth. That exploration finds fulfilment as one walks along the corridor.

The murals have been done with meditative care. These are highly complex and sophisticated works of art. The once-bare walls and ceilings of the state corridor, running through the North-South axis of the Bhavan, came alive in a celebration of bright colours with these murals. The use of the gold leaf in the paintings adds to the lustre of the motifs. They drench the viewer in shanta rasa, the foundational element of art in India.

Then there are the frescoes, which were selected by the British, for the grand ballroom now, the Ashoka Hall. Beautifully executed, they are about physical might and material excellence. A large painting gifted by the Shah of Iran to the British has been pasted on the ceiling of the Hall, using the marouflage technique. It depicts a hunting expedition of the royal family of Persia. The contrast with the spirituality-imbued murals selected by the Indian presidents is too hard to miss.

One of the striking aspects of the state corridor murals is the 73 shlokas from the Bhagvad Gita, painted in calligraphic style. In his writings, Mahatma Gandhi had personified the Gita as a mother in whose comforting lap he found answers to the most difficult questions of life. Though not a great admirer of the building, the Mahatma would have been very pleased with the prominence given to these verses. Nearly a third of the shlokas have been taken from the 11th Chapter of the Bhagvad Gita, which describes Krishna as the all-pervading cosmic self. The essence of the chapter is that an impersonal and impartial cosmic law sustains the universe, therefore, it is futile to be buffeted by individual impulses. Many shlokas from the second chapter, Sankhya-yoga, have also been depicted through the murals, besides verses from five other chapters. The second chapter contains metaphysics and ethics of the Gita. One shloka reminds one of the story of Janaka, the philosopher-king whose enlightenment enabled him to provide ideal governance to his people. The verse says,

āpūryamāṇ amachalapratiṣhṭhaṁ-

samudramāpaḥ praviśhanti yadvat

tadvatkāmā yaṁ praviśhanti sarve

sa śhāntimāpnoti na kāmakāmī

(Just as the ocean remains undisturbed by the flow of waters merging into it, similarly the wise one who is unmoved despite the flow of desirable objects around him attains peace, and not the person who seeks to satisfy desires.)

This message of equanimity, of adhering to the ultimate truth, of excellence with dispassion is a defining feature of what may be called the first building of the country, the residence and workplace of its first citizen. The main dome of a building can be said to be its head or face. The grand dome of the Rashtrapati Bhavan is an architectural homage to the Sanchi Stupa and the Buddha’s message of compassion and love. The murals in the state corridor are, likewise, a reflection of our philosophy and culture.

Sunil Trivedi is Officer on Special Duty (Research), Rashtrapati Bhavan