On his birth centenary, a tribute to Satyajit Ray through images captured by his friend and colleague of over two decades, the late photographer Nemai Ghosh

The book Faces and Facets: Satyajit Ray in Colour, released last year, shows us the polymath and auteur through the eyes of his photo-biographer Nemai Ghosh, who died last year

(Ghare Baire, 1984). Ray composes music on a synthesiser at home, 1982. “I am afraid Calcutta is now short of musicians,” he said in

the mid-1980s, “and you have to fall back on the synthesiser much of the time. For instance, there’s no oboeist in Calcutta, no cor anglais, horn or brass players. I’m not very happy using the synthesiser, anywhere in my films, except for the oboe tone: that’s one tone the synthesiser can produce very faithfully.” Photographs by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

(Ghare Baire, 1984). Ray composes music on a synthesiser at home, 1982. “I am afraid Calcutta is now short of musicians,” he said in

the mid-1980s, “and you have to fall back on the synthesiser much of the time. For instance, there’s no oboeist in Calcutta, no cor anglais, horn or brass players. I’m not very happy using the synthesiser, anywhere in my films, except for the oboe tone: that’s one tone the synthesiser can produce very faithfully.” Photographs by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)Text by Andrew Robinson

“In a sense, the possibilities of fusing Indian and Western music began to interest me from Charulata (1964) on. I began to realise that, at some point, music is one … Especially for my contemporary films … I knew that raga music alone just would not do: because the average, educated middle-class Bengali may not be a sahib, but his consciousness is cosmopolitan, it is influenced by Western modes and trends. To reflect that musically you have to blend — do all kinds of experiments. Mix the sitar with the alto and the trumpet and so on.”

—Satyajit Ray

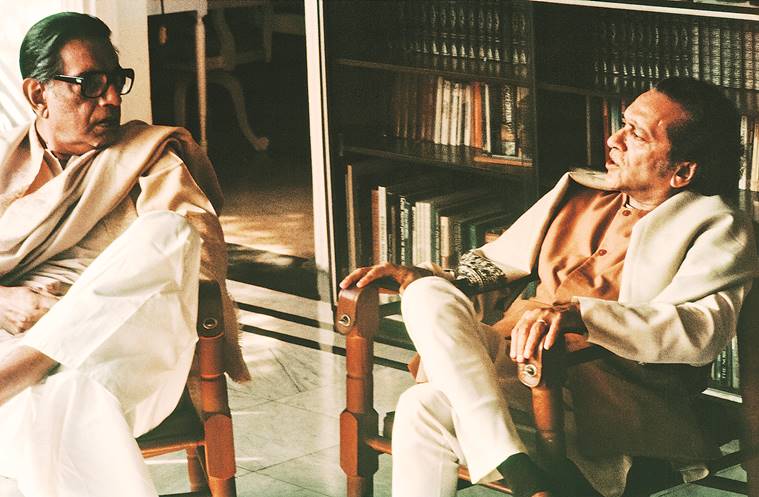

Ray with sitarist and composer Ravi Shankar in Calcutta, 1983, following his first heart attack. They first got to know each other in the 1940s, and, in the 1950s, Shankar composed some inspired music for the Apu Trilogy (Pather Panchali, 1955, Aparajito, 1956, and Apur Sansar, 1959) and The Philosopher’s Stone (Parash Pathar, 1958). Despite striking differences in personality and musical taste, they admired each other and remained friends until Ray’s death (on April 23, 1992). Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

Ray with sitarist and composer Ravi Shankar in Calcutta, 1983, following his first heart attack. They first got to know each other in the 1940s, and, in the 1950s, Shankar composed some inspired music for the Apu Trilogy (Pather Panchali, 1955, Aparajito, 1956, and Apur Sansar, 1959) and The Philosopher’s Stone (Parash Pathar, 1958). Despite striking differences in personality and musical taste, they admired each other and remained friends until Ray’s death (on April 23, 1992). Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

“I find I am inimical to the idea of making two similar films in succession… I do not know if this suggests a restlessness of mind, a lack of direction, resulting in a blurring of outlook—or if there is an underlying something which binds my disparate works together. All I know is that I am interested in many aspects of life, many periods in history, many styles and many genres of film-making.”

—Satyajit Ray

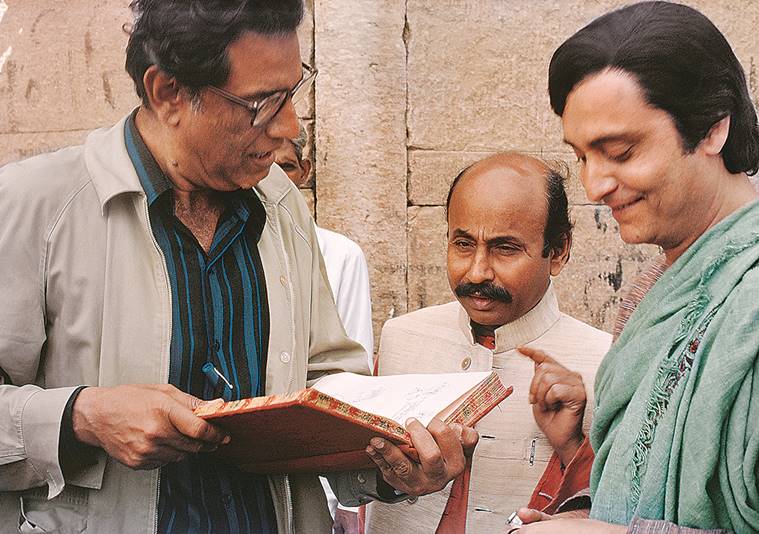

Ray with artist Benode Bihari Mukherjee in Santiniketan, West Bengal, 1972. Mukherjee was Ray’s favourite teacher when he was an art student at Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan in 1940-42. And, he remained an inspiration 30 years later to Ray, who made the documentary The Inner Eye about Mukherjee (who addressed his former student as “Satyajit”, rather than his popular nickname “Manik”). Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

Ray with artist Benode Bihari Mukherjee in Santiniketan, West Bengal, 1972. Mukherjee was Ray’s favourite teacher when he was an art student at Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan in 1940-42. And, he remained an inspiration 30 years later to Ray, who made the documentary The Inner Eye about Mukherjee (who addressed his former student as “Satyajit”, rather than his popular nickname “Manik”). Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

“I never imagined I would become a film director, in command of situations, actually guiding people to do things this way or that. No, I was very reticent and shy as a schoolboy and I think it persisted through college. Even the fact of having to accept a prize gave me goose-pimples. But from the time of Pather Panchali (1955), I realised that I had it in me to take control of situations and exert my personality over other people and so on — then it became a fairly quick process. Film after film, I got more and more confident.”

— Satyajit Ray

The Elephant God (Joi Baba Felunath, 1979). Ray rehearses with Santosh Dutta (Jotayu) and Soumitra Chatterjee (as the sleuth Felu; far right) in Varanasi (Benares), 1978. Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

The Elephant God (Joi Baba Felunath, 1979). Ray rehearses with Santosh Dutta (Jotayu) and Soumitra Chatterjee (as the sleuth Felu; far right) in Varanasi (Benares), 1978. Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

“Since it is the ultimate effect on the screen that matters, any method with an actor that helps to achieve the desired effect is valid … Sometimes it’s easier with non-professionals. I have no definite system. You have to modify your technique all of the time. But you have to get to know the person you are working with, know his methods and his abilities and his intelligence. Sometimes I use them as complete puppets, and I do not tell them anything about motivation at all. I just try to get particular effects.”

—Satyajit Ray

The Chess Players (Shatranj ke Khilari). Ray, who was once a keen amateur chess player, rehearses how to play the game on screen with Saeed Jaffrey (Mir) and Sanjeev Kumar (Mirza) in Calcutta, 1977. Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

The Chess Players (Shatranj ke Khilari). Ray, who was once a keen amateur chess player, rehearses how to play the game on screen with Saeed Jaffrey (Mir) and Sanjeev Kumar (Mirza) in Calcutta, 1977. Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

“When a writer is at a loss for words, he can turn to his Thesaurus; but there is no Thesaurus for the film-maker. He can fall back on clichés, of course — goodness knows how many films have used the snuffed-out candle to suggest death — but the really effective language is both fresh and vivid at the same time, and the search for it is an inexhaustible one.”

—Satyajit Ray

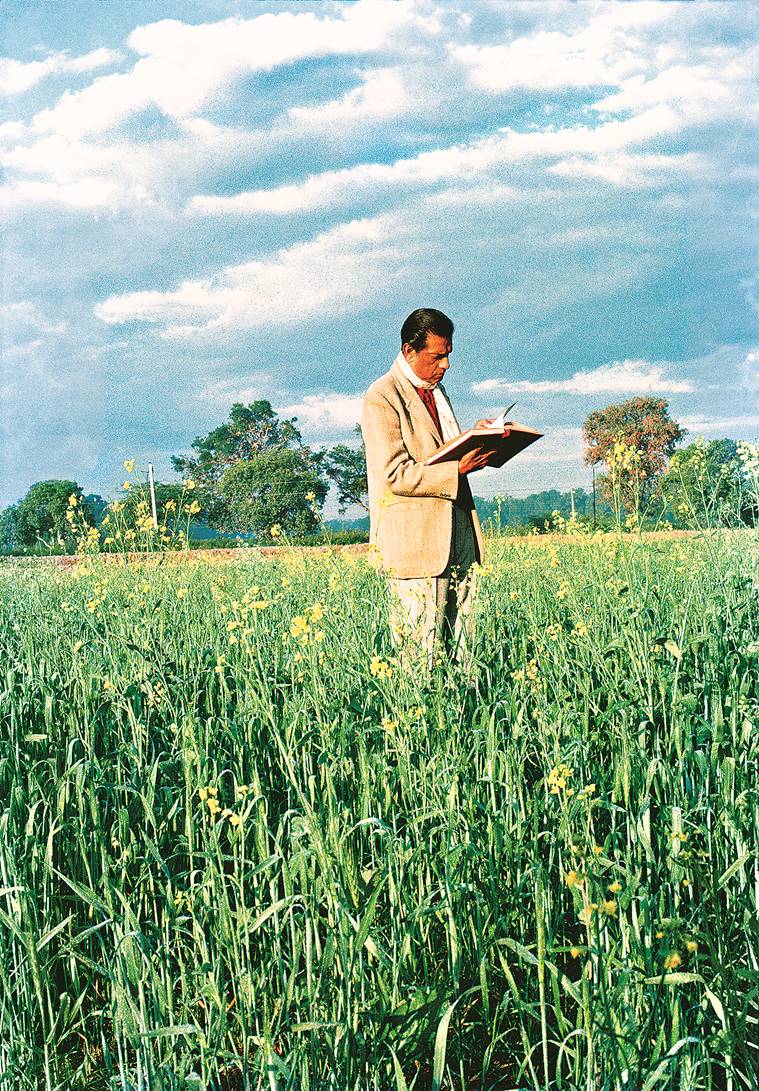

Shatranj ke Khilari; left). Ray consults his kheror khata (red notebook) in a field of mustard near Lucknow, 1977. The field appears in the dialogue of the film when Mirza (Sanjeev Kumar ) sarcastically asks Mir (Saeed Jaffrey) if they are supposed to play chess in it, for lack of any suitable building nearby. Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

Shatranj ke Khilari; left). Ray consults his kheror khata (red notebook) in a field of mustard near Lucknow, 1977. The field appears in the dialogue of the film when Mirza (Sanjeev Kumar ) sarcastically asks Mir (Saeed Jaffrey) if they are supposed to play chess in it, for lack of any suitable building nearby. Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

“This whole business of creation, of the ideas that come in a flash, cannot be explained by science. It cannot. I don’t know what can explain it but I know that the best ideas come at moments when you’re not even thinking of it. It’s a very private thing really.”

—Satyajit Ray

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05