‘My stories are about us, about people around us’

Director Nagraj Manjule on his latest film, nurturing talent and his cinematic universe that propels his method of storytelling

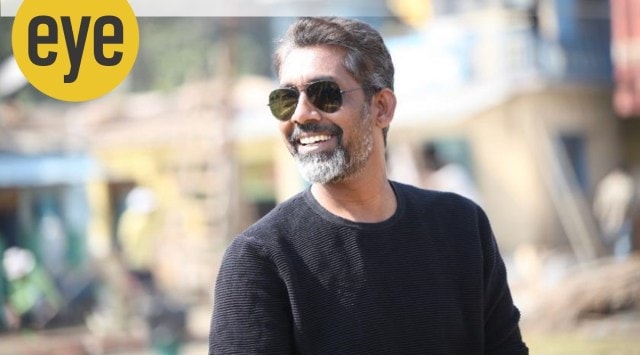

Nagraj Manjule.

Nagraj Manjule.When Nagraj Manjule watched the video of Ankush Gedam dancing during a Ganpati immersion procession in Nagpur’s Gaddigodam area, the filmmaker was instantly captivated by his unbridled energy, swagger, and spirit. It was 2017 and Manjule was in the process of finalising the cast of Jhund, which tells the story of a sports teacher (Amitabh Bachchan) training young slum-dwellers of Nagpur to play football and unwittingly propels them towards a better life. In the next few days, the filmmaker received several other videos of then 24-year-old Gedam running and playing football. They were sent by Manjule’s associate and younger brother, Bhusan, with the message: “Don mil gaya (We have found Don)”.

Before the making of Jhund, Gedam was drifting through life after Class XII — taking up odd jobs as a delivery boy and working in eateries — while nursing the ambition of joining the police someday. Manjule found Gedam’s screen presence fetching, even though his look with long hair was developed later. “Be it the casting for Fandry (2013), Sairat (2016) or just-released Jhund — my belief is that we should choose an actor who appears close to the character. But they need not be identical,” says the Pune-based director, known for “authentic casting” to imbue the storytelling with his signature raw and realistic vibes.

In the film, Amitabh Bachchan trains young slum dwellers in football.

In the film, Amitabh Bachchan trains young slum dwellers in football.

The 44-year-old director’s casting motto combined with his sharp instinct has set a benchmark when it comes to introducing new faces on the Indian screen. He has tried fresh casting since his very first work, the National Award-winning short film Pistulya (2010), when he cast young Suraj Pawar, who belongs to the backward Pardhi community from Ahmednagar, in the titular role. He later played Pirya in Fandry (2013) and Prince in Sairat (2016). In Fandry, Somnath Awghade, who had dropped out of school after Class VII then, essayed the character of Jabya, a teenager infatuated with an upper-class girl, though acutely aware of his lower caste identity. In Sairat, too, he introduced Rinku Rajguru as feisty Archie, and Akash Thosar as the affable Parshya. Rajguru was a Class VII student and Thosar was pursuing his bachelor degree when they made their landmark debut. They are also in Jhund — Rajguru as a football player from a remote village and Thosar as a local toughie — which featured nearly 30 newcomers. The debutants include Sayli Patil, Priyanshu Kshtriya (Babu), Allen Patrick, Angel Anthony and Kartik Uikey.

Before these handpicked prospective actors face the camera on Manjule’s sets, they undergo extensive training, rehearsals, and workshops. Prior to the making of Fandry and Sairat, most of the young actors in the cast lived with Manjule and other members of his team. The comparatively bigger cast of Jhund lived in a bungalow in Pune’s Kothrud for nearly a year. “Whenever we write a story, we create a world that’s based on the imagination. At times, it’s based on real life, then you add your imagination to it and build the characters,” says Manjule, who has now set up a farmhouse in Narhe, in the outskirts of Pune, and hosts multiple creative activities there.

A still from the film.

A still from the film.

Fondly called “Anna” by the young actors, Manjule’s tried-and-tested method involves a lot of hand-holding, boosting their morale, and even enacting the scenes. “I didn’t know anything about acting. I used to just follow Anna’s instructions while shooting for Fandry. For Jhund, I had to learn how to play football and practised for nearly one-and-half years,” says Awghade, who plays the role of Imraan in Jhund. Unlike him, Gedam was an experienced football player and had taken part in slum tournaments. The 29-year-old, however, was not sure if he could cry on camera, having failed to do so once during his audition. “In one crucial scene, I’m drunk, sad, crying, and, also, angry over not getting my passport. Anna not only showed me how to do it but also gave them the confidence to handle different emotions at the same time,” recalls Gedam.

From the onset, it is evident that Jhund is not merely a sports film. It’s a social drama that makes a plea for society to be more inclusive and empathetic towards those living on the margins.

This ambition is reflected in the way the film captures the nail-biting match between Gaddigodam’s team and that of an elite college in the neighbourhood. “We designed everything in detail — the movement of the ball, the emotion of the players, and the response of the crowd,” he says, about the sequence which was shot over two weeks.

A still from the film.

A still from the film.

Elaborate designing and detailing have also gone into drawing a convincing performance from the group of novice actors sharing the screen with Bachchan, the original angry young man of Indian cinema. “I had rehearsed with them prior to the shoot. They knew they had to act without any fear of the camera or being intimidated by Bachchan Sir’s presence,” says Manjule, and adds that the credit goes to Bachchan for putting everyone at ease.

Manjule tells Jhund’s story in a certain mellowness and sass. His slum dwellers exude confidence. Dressed in their finery, they scale the wall to enter the college playground where their match with its students is being held. The director attributes the shift in his tone to the characters’ demands. “Fandry’s Jabya has an inferiority complex but he can hurl a stone too. Sairat’s Parshya is delicate but also daring. In Jhund, Don, Babu, Raziya, and Monica are different from them,” he says, about his new bunch of characters who are assertive, irrespective of all the adversities they encounter.

A still from the film.

A still from the film.

As someone who is aware of the faultlines in our society, does Manjule feel a rage? “There is rage but not blind rage. I had frustrations when I was young. As I went for higher studies and started doing better, I learnt that it is not always necessary to lash out,” he says. After a pause, he adds: “Yatna hai dil mein (there is pain in my heart). However, at different stages of life, you feel and react differently.” That could be the reason that when Bachchan’s character tells his proteges that they can’t spend their entire life fighting, it rings a bell among the characters who had never shied away from courting trouble earlier. Hot-tempered Don, when harassed by a local muscleman, advises his friend Imraan to say sorry and end the matter. “This is a realisation that I had myself,” says Manjule.

While the movie traces the initiatives taken by Vijay Barse, founder of Slum Soccer, the writer-director has let several autobiographical elements seep into the script. Though many people assumed Monica’s trouble alluded to the controversy surrounding the National Register of Citizens (NRC), Manjule says that the story track was inspired by his struggle. “I had to run around for the caste certificate and to get my passport done. A number of my relatives work in stone quarries. They still don’t have official identification documents,” he says.

For Manjule, who has written scripts of all his directorial work, every story has its own distinct nature. “That’s sacrosanct for me. I want to maintain the story’s uniqueness and temperament. Usually, I don’t start writing a script until the story has taken shape in my mind,” says Manjule.

Addressing the criticism that the story of Jhund meanders in the second half, Manjule says: “Who says that every story has to be told in a certain way? When the title of my film is Jhund, you should expect the story of jhund (a group of characters).”

There is a perceivable change in the way Jhund handles romance, almost with a touch of fairy tale. Manjule, however, disagrees. “Does it come across as a fairy tale because this boy (Don) hasn’t studied much and thoda atpata sa hai (a bit peculiar) while the girl (Bhavana) is rich and drives a Mercedes? I had once written a poem about how our simple dream becomes a fairy tale. Loving a girl is not an impossible dream. I would give credit to Bhavana that she steps down from higher status in society and falls in love with Don. She can, perhaps, help him lead a better life. If this is a fairy tale, there should be more of them,” says Manjule.

A still from the film.

A still from the film.

Manjule is happy that his movies have initiated conversations regarding some key social issues. “Without a diagnosis, you won’t find the cure. What I try to say through my movies, probably concerns many people. It’s not about me alone. When dinosaurs attack human beings in a movie, no one has anything to say. What can you tell a dinosaur? It is imaginary. But my stories are about us, about people around us,” he says.

The director, who has been called “an excellent storyteller” by actor Aamir Khan and “fearless” by director Anurag Kashyap, however, does not rule out experimenting with different kinds of stories and genres in the future. Manjule’s next movie, Ghar Banduk Biryani (2022), features him as an actor. Apart from making an appearance in all his feature films, he has acted in several other movies including Highway (2015), The Silence (2016), and Naal (2018).

For Manjule, acting is a welcome break before he takes up the ambitious project on Shivaji Maharaj. “Today, I understand Shivaji better. He dreamt big. He and his ideologies have united the people of Maharashtra in spite of all the societal divisions,” he says. In a much-talked-about scene in Jhund, Bachchan is shown paying his respect to Shivaji Maharaj, Jyotirao Phule, Shahu Maharaj and Bhim Rao Ambedkar.

Just like sports, cinema has the power to transform lives. After Manjule nurtured the talent of the youngsters in his cast and drew out compelling performances that has given them a new identity, almost all of them today aspire to have a career in movies. Thosar and Rajguru have already worked on several projects after Sairat. Awghade, who went back to school after filming Fandry, plans to learn the ropes of filmmaking after completing his graduation. It’s the same for Gedam. “My life was too hard earlier. Now, people, who never cared about me, have been calling me to compliment my work. I am enjoying this phase of my life. I am ready to take up any kind of job that I get in the world of cinema,” says Gedam.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05