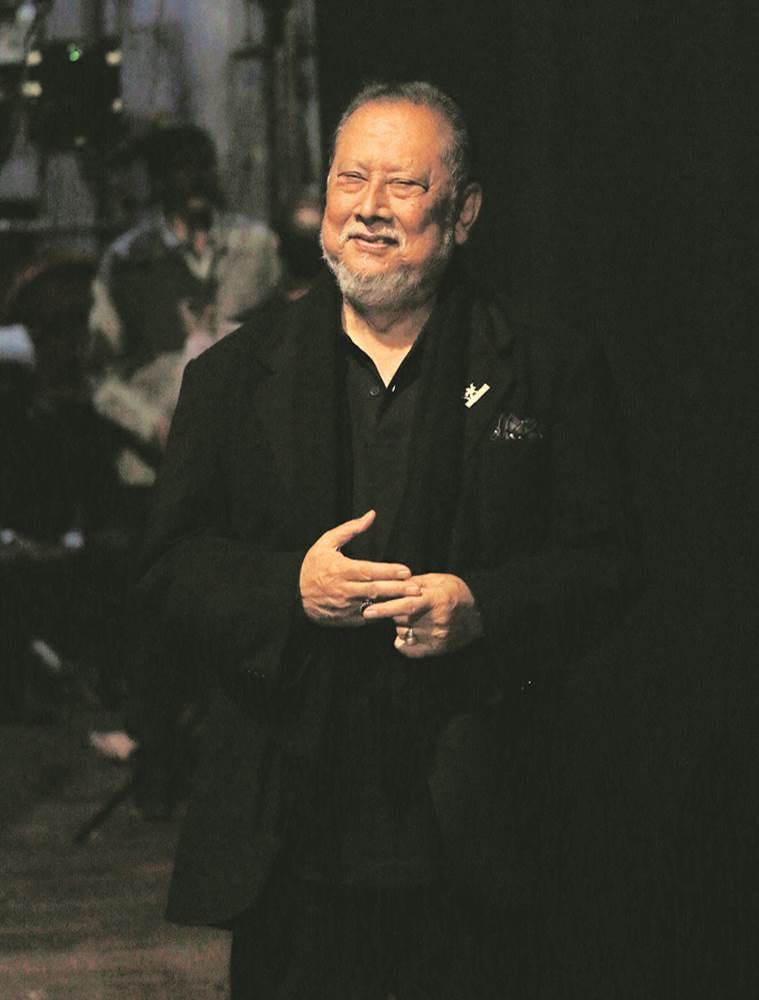

When he was a young boy, Ratan Thiyam, 72, dreamt of going to Cuba to become a revolutionary like Che Guevara. “I read his books and was inspired by his ideas and way of life,” he says. Thiyam’s rebellion expressed itself through theatre. For 45 years, his plays have challenged power — whether it was the colonial hangover that prevented India from finding pride in its ancient traditions after Independence or our inherited stereotypes about good and evil — by subverting them in form and content.

On February 21, more people than Kamani auditorium could hold gathered at the gate to watch Thiyam’s latest production, Lairembigee Eshei (The Song of the Nymphs). A small number could understand the language in which he works, Manipuri, but they were all sure the new play would live up to Thiyam’s reputation. Older members in the queue boasted of watching early shows of Thiyam’s spectacular tragedies, Karnabharam (1976) and Urubhangam (1981), in which Karna and Duryodhana, considered the antagonists in the epics, were upheld as heroes. When seen in the backdrop of Manipur, where security forces have been engaged with insurgent groups fighting for self-determination, the plays become a powerful comment on rethinking our notions of heroes and villains. Both plays are based on texts by Bhasa, one of the earliest Sanskrit playwrights, who was fiercely anti-establishment.

The protagonists of Lairembigee Eshei are nature and human beings. It was staged as part of the closing ceremony of the 21st Bharat Rang Mahotsav, the theatre festival of the National School of Drama in Delhi. In the play, a pleasure-loving king, who cuts trees and destroys forests to fuel his desires, is cursed with an incurable disease by mother nature. As he suffers, a nymph — a personification of nature — comes to the king and says, “If you keep behaving without respect for us, you will be cursed again and again.” Ironically, the performance took place on a day when Delhi’s air quality index was in the “unhealthy” zone. “We are living in a time of an environmental crisis…Your soul is collecting the garbage of the contemporary world from the news of battlefields, corruption, bribery cases and other negatives. So, it may be helpful to go back to nature and try to understand what it wants to give to you. Nature provides us with a lasting form of pure energy but we are ignoring it,” says Thiyam in the play. In a powerful scene, a group of birdcatchers trips and falls as the birds cluck and dance around them — symbolising that the human race is fighting a losing battle with nature.

“I don’t make a play for the sake of doing a production. An artist lives in society and gets affected by what happens to it. It is only when ideas start knocking on my head and giving a kick to my buttock that I start to create a play… I believe that, in order to work, a piece of art must strike at the system and break convention,” he says. In 1989, Thiyam was awarded the Padma Shri for his work in theatre. In 2001, he returned it to protest what he perceived as the Centre’s lack of support to resolve the crisis in the state. “Life is not normal in the Manipur valley for the past month. No tangible efforts or urgency is visible on the part of the Centre. It is decaying by the day and there is no helping hand coming forward. It is not a disrespect for the civilian honour of Padma Shri conferred on me, it is a compulsion of my bleeding heart. Although it is a very painful decision, I am, as a protest, relinquishing this honour,” he wrote at the time.

Ratan Thiyam (Photo: Chorus Repertory Theatre)

Ratan Thiyam (Photo: Chorus Repertory Theatre)

Lairembigee Eshei emerged in autumn last year when Thiyam sat in his garden and watched the falling leaves. He couldn’t shake off the feeling that this barrenness would be how the world would look if it ended in an ecological apocalypse. “I began to write…until, 13 days later, I had the script of the play,” he says.

Thiyam is one of the leading figures in the Theatre for Roots movement, with BV Karanth and KN Panniker, among others. After Independence, this form of theatre was a process of decolonisation, in which art practitioners embraced their traditional and indigenous practices as a way to assert their Indian identities. Thiyam, who speaks six languages and understands eight, makes plays only in Manipuri (without subtitles, as he wants audiences to understand the play by watching it, rather than reading). His finely choreographed movements are inspired by a gamut of dances and movement forms drawn from Manipur, the rest of India, as well as Asian cultures such as Japanese Noh and Kabuki forms, among others. Stylised traces of Nat Sankeertana manifest themselves when the widows lament after the bloody battle in Uttar Priyadarshi (1996); characters in Macbeth glide their feet on the ground in a movement inspired by the Noh and Kabuki, among others. In his group, Chorus Repertory Theatre, Thiyam introduced Thang-Ta, a martial arts form from Manipur, as one of the techniques to keep actors’ bodies fit and flexible.

What sets Thiyam apart from his contemporaries is that he has been among the few directors to take his productions to international platforms. This is an uncommon practice in India where a majority of plays travel around the region or to a few cities in the country due to a lack of financial support or low production quality. As a representative of the Indian stage, Thiyam has played at iconic venues and theatre festivals. Urubhangam was performed at the Edinburgh International Theatre Festival in 1987 and won the prestigious Fringe First Award, a first for India. Long before Yanni performed at the Acropolis, Thiyam had presented Urubhangam at the historical ruins of Athens.

Story continues below this ad

Lairembigee Eshei (Courtesy: Bharat Rang Mahotsav)

Lairembigee Eshei (Courtesy: Bharat Rang Mahotsav)

One of the reasons for the international appeal of Thiyam’s plays is the balance he has achieved in his traditional aesthetics and global production values. His plays are critically acclaimed as visual spectacle and epic productions. “I don’t use large sets and prefer to have characters carry the props on stage. With these, I create an image in every scene that is replaced by another design in the following scene. It is as if I paint and erase, but the layer thickens on the canvas of your mind. At the end, you have quite a lot of ideas. This is how I carry out my discussion, through sound, song, tonal quality, movement and design,” he says. His stage is predominantly black and the action takes place in pools of light. “Two things are very important. One is darkness and the other is silence. I believe that the darker the stage is, the brighter you see. The more you are silent, the more you are not,” he says.

The tours have enabled Thiyam to convey his political anguish. “When you wake up and read the newspaper, the only news you get are of death, terrorism and violence. I don’t want to be a politician.

I am a theatreperson and doing a production is enough for me,” he says. His Manipur Trilogy, which deals with the crisis of culture and violence in Manipur, began with Nine Hills One Valley (2006). It was followed by HeyNungshibi Prithivi (My Earth, My Love) and Wahoudok (Prologue), both in 2007.

Thiyam began life, literally, in costume boxes. His parents, Thiyam Tarun Kumar and Bilasini Devi , were Manipuri classical dancers, who were always on tour. They were performing in West Bengal when Thiyam was born in Nabadwip, a sacred town that had a sizeable Manipuri community. “Travelling with my parents exposed me to many art forms. I would be playing in the wings or the green rooms while some of the best artistes of Manipur would be rehearsing. I was soaking it all in, though I didn’t realise it then. This was also the time that I learnt to observe people, from the pedestrians to the policemen. But the travel was affecting my studies. I promised myself I would never take up performing arts. I told my parents I wanted to return to Imphal,” he says.

Story continues below this ad

He was left with his paternal uncle, a well-known doctor, in Imphal and enrolled at Johnstone High School. “The family tried very hard to make me a doctor because I was good in studies but I was attending art school and writing a lot. The first of my six novels was published in 1965, when I was 22. I also wrote poetry and short stories. It was when the Cultural Forum of Manipur appointed me the associate editor of their journal, Ritu, that I began to review theatre. What did I know about theatre? Zero. I needed to learn,” he says.

The history of performances in Manipur can be traced to the fertility cults and ancestor worship of the 12th century. In the next 200 years, mandap-style open religious theatres were showcasing Hindu epics, which changed into closed spaces with wooden boxes in the front rows to accommodate the colonial middle class. The Manipuri Dramatic Union introduced ticketed shows in 1931. After the state integrated with India in 1949, the Nehruvian ethos entered the stage. By the 1960s, when Thiyam was a teen, Manipur was becoming dissatisfied with Indian rule. This led to a surge in production by young people, led by artists such as M Biramongol, defiantly searching for their identity and indigenous roots. The colourful and commercial Parsi Theatre was popular in Manipur, which Thiyam joined as an actor in the late 1960s.

Ratan Thiyamin (Express Photo by Prem Nath Pandey)

Ratan Thiyamin (Express Photo by Prem Nath Pandey)

By the 1970s, separatist ideology was driving a lot of experimental productions. Around this time, the Absurd theatre of Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco and Jean-Paul Sartre was being adapted Manipur. “I was not knowledgeable about European theatre, so I started studying it,” he says. In 1971, he gained admission to the National School of Drama (NSD) in Delhi, where the director was the formidable theatre veteran Ebrahim Alkazi. “I remember Ratan was studious, curious and always experimenting with sounds and movements. In him, I saw all the qualities of a theatre maker,” says actor Rohini Hattangadi, Thiyam’s classmate from NSD.

Thiyam passed out of NSD in 1974, the school’s first graduate from Manipur. He would return to NSD as director from 1987 to ’88. “He was a strict disciplinarian. If classes were starting at 8 am, he would stand at the reception to see when students came in. If a student was late, he wouldn’t comment but only look at his watch,” says Suresh Sharma, director-in-charge, NSD.

Story continues below this ad

At the drama school, Thiyam learnt about Western theatre forms, discipline and methods of acting. “I came out knowing all about Greek and European theatre but we were not taught traditional theatre. I don’t eat with fork and spoon. I eat with my hand. I don’t have a dining table. Hence, Western theatre was very good but I wanted to learn about indigenous Indian theatre. After all, we go to the roots to learn of our identity. You cannot say, ‘I am living without a past’,” he says.

Returning to Manipur in 1974, Thiyam went to his father and asked him to give him lessons in traditions and performing art forms. For the next four years, he learned from gurus and elders about traditional forms and rituals of the state and other cultures.

In 1976, Thiyam founded the Chorus Repertory Theatre (CRT), famously telling his 12 recruits, “Theatre will give you bread but not butter”. Why did Thiyam return to Manipur after NSD when his classmates were reaching out to Bollywood or Delhi theatre? Manipur was caught in a churn of sociopolitical unrest, poverty, violence and repression. Even early this year, the administration did not see it fit to remove the controversial Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, which was imposed in Manipur in 1980. “Manipur did not have big industries, enough employment opportunities or housing. To construct one road took 65 years. It was very important for me to understand the gap between what the central government was saying and what was happening. When the system is going wrong, we have to protest and theatre is the strongest way to do so,” says Thiyam.

Chakravyuh (Courtesy: Chorus Repertory Theatre)

Chakravyuh (Courtesy: Chorus Repertory Theatre)

He built a two-acre campus with members of his group that was surrounded by trees, birds and lily pools. It has been rebuilt half-a-dozen times due to monsoon flooding. Here, Thiyam went to war. He created Urubhangam; in 1984, and staged Andha Yug, Dharmavir Bharati’s classic that is set in the last day of the Kurukshetra war. “When I make a play based on the Mahabharata, I am not telling the story of an epic but of the reality around myself. I pick a play and try to adapt it to the situation,” says Thiyam. His Chakravyuh (1984) was inspired by the war of the USSR and the US in Afghanistan. On the battlefield of the Kauravas and Pandavas, it is the flags of the Cold War countries that flutter.

Story continues below this ad

The senior theatre director is notoriously meticulous — about platforms on the stage being of equal height, of a dancer’s spine being straight, of the sound designer allowing for a few moments of silence after the lights fade out. When Thiyam’s imagination begins to soar too high, it falls on Thawai, 38, his son, assistant director at CRT, to give him a reality check.

Thiyam, who has been suffering from health problems in the past few years, is still carrying out that most political of acts — thinking. The 21st Bharat Rang Mahotsav, at which Lairembigee Eshei was staged, coincided with a divisive election campaign and a battle for the ballot in Delhi. A metro ride away from the NSD, women have been sitting in protest against government policies since December 2019. “Everything happens in a cycle, even politics. The most important thing in a political cycle is that it includes the thoughts and ideas of the people. Once the wheel has started slowing down, it is because of the obstacles and protests coming from the people. A small protest is a very big protest because it means that everyone is disagreeing and this is very dangerous to the establishment,” says Thiyam.

A scene from the performance of Macbeth (Photo: Chorus Repertory Theatre)

A scene from the performance of Macbeth (Photo: Chorus Repertory Theatre)

Ratan Thiyam (Photo: Chorus Repertory Theatre)

Ratan Thiyam (Photo: Chorus Repertory Theatre) Lairembigee Eshei (Courtesy: Bharat Rang Mahotsav)

Lairembigee Eshei (Courtesy: Bharat Rang Mahotsav) Ratan Thiyamin (Express Photo by Prem Nath Pandey)

Ratan Thiyamin (Express Photo by Prem Nath Pandey) Chakravyuh (Courtesy: Chorus Repertory Theatre)

Chakravyuh (Courtesy: Chorus Repertory Theatre)