What is the World Press Freedom Index and how does it measure countries?

Anurag Thakur, the Union Minister of Information & Broadcasting, had said earlier that the Indian government “does not subscribe to its views and country rankings.” How does the index calculate its rankings?

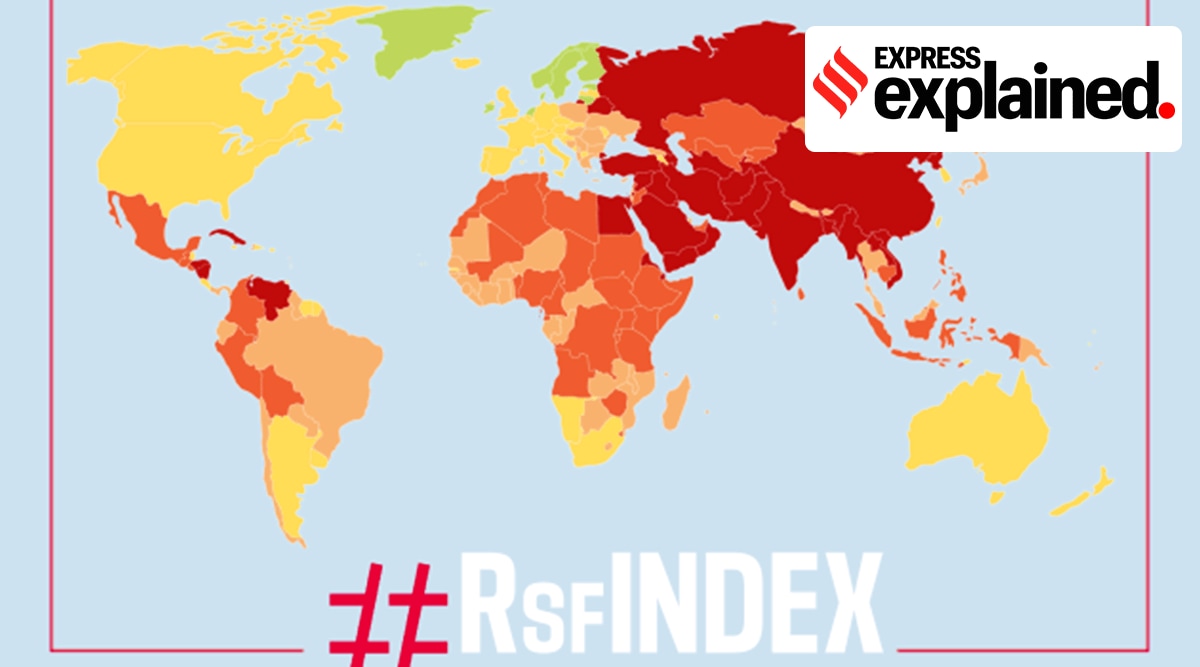

The index develops a score between 0 (for the worst possible performance in terms of securing press freedom) and 100 (the best possible score). (Via Twitter.com/RSF_eng)

The index develops a score between 0 (for the worst possible performance in terms of securing press freedom) and 100 (the best possible score). (Via Twitter.com/RSF_eng) In the 2023 edition of the World Press Freedom Index, released annually by the non-profit organisation Reporters Without Borders, India has slipped 11 places to the 161st rank out of 180 countries – ranking below countries such as Somalia (141), Pakistan (150), and Afghanistan (152).

The report released on Wednesday (May 4) was highlighted by associations of journalists, such as the Press Club of India. In March this year, the Union Minister of Information & Broadcasting Anurag Thakur had said in a written reply in the Lok Sabha that the Indian government “does not subscribe to its views and country rankings”, and does not agree to the conclusions drawn by the organisation.

Thakur states this was “For various reasons including very low sample size, little or no weightage to fundamentals of democracy, adoption of a methodology which is questionable and non-transparent, etc.”

What has the report said on the state of press freedom globally and how does Reporters Without Borders create this index?

First, what is Reporters Without Borders?

Reporters Without Borders or Reporters Sans Frontiers (in French) is a global media watchdog headquartered in Paris, France, and it publishes a yearly report on press freedom in countries across the world. “We are neither a trade union nor a representative of media companies”, it states on its website.

“Founded in 1985… RSF is at the forefront of the defence and promotion of freedom of information. Recognised as a public interest organisation in France since 1995, RSF has consultative status with the United Nations, UNESCO, the Council of Europe and the International Organization of Francophonie (OIF),” it adds.

RSF has 134 correspondents around the world and is also involved in delivering daily updates on jailed journalists, instances of press censorship, etc. “We insure journalists on missions in high-risk areas and lend helmets and bulletproof vests. We assist them with legal action when they are victims of abuse, and assist reporters forced to flee with asylum applications,” it says. Perhaps one of its most visible initiatives is the World Press Freedom Index.

How does it measure press freedom?

In its website’s Methodology section, RSF states, “Press freedom is defined as the ability of journalists as individuals and collectives to select, produce, and disseminate news in the public interest independent of political, economic, legal, and social interference and in the absence of threats to their physical and mental safety.” The index then compares levels of press freedom globally based on this definition.

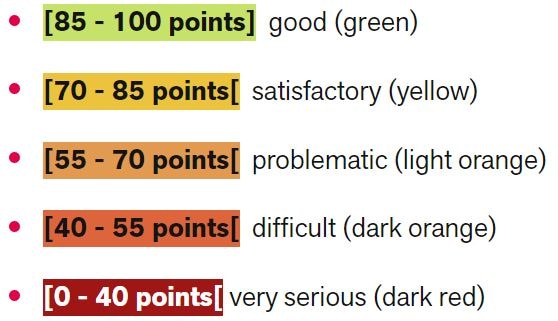

It develops a score between 0 (for the worst possible performance in terms of securing press freedom) and 100 (the best possible score). This year, Norway scored 95.18 at the first position, North Korea was at 21.72 and India scored 36.62. A score below 70 falls under the ‘problematic’ category.

The scale of the scores given by the World Press Freedom Index.

The scale of the scores given by the World Press Freedom Index.

This score is based on two indicators:

*a tally of abuses against media and journalists in connection with their work, arrived at by monitoring and analysing news stories on journalists being imprisoned or killed.

*a qualitative analysis of the situation in each country or territory based on the responses of “press freedom specialists”, including journalists, researchers, academics and human rights defenders, to an RSF questionnaire available in 24 languages. These include Arabic, Chinese, English, Hindi, Spanish, etc.

To maintain the tally of abuses, the site has a barometer with real-time information about abuses against journalists in the course of their work. In the case of India, it notes the murder of journalist Shashikant Warishe this year, after which Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis Saturday in February ordered a Special Investigation Team (SIT) probe. Warishe was reporting on the setting up of the Ratnagiri Refinery & Petrochemicals Ltd (RRPCL) in Barsu, a project which has faced stiff opposition from locals.

In the questionnaire for qualitative analysis, having more than 100 questions, each country’s score is evaluated after assessment of the state of media across five factors: the political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context and safety.

Questions with yes/no choices or multiple choices are given out, such as “In the past 12 months, have the authorities blocked accounts or had posts deleted in response to the posting or sharing of journalistic content?” and “Have any journalists been assaulted in the past 12 months?”

What does the 2023 report say about press freedom globally?

The index states in 2023 that “the environment for journalism is ‘bad’ in seven out of ten countries, and satisfactory in only three out of ten.”

It also highlighted concerns of propaganda fake news, further heightened given the rise of artificial intelligence technology. Programmes like Midourney, which can create lifelike images based on a simple text prompt, were mentioned in this context.

“North Korea (180th), China (179th), Vietnam (178th), Myanmar (173rd) – Asia’s one-party regimes and dictatorships are the ones that constrict journalism the most, with leaders tightening their totalitarian stranglehold on the public discourse,” it states, terming China as “The world’s biggest jailer of journalists and press freedom advocates.”

It adds that “The other phenomenon that dangerously restricts the free flow of information is the acquisition of media outlets by oligarchs who maintain close ties with political leaders,” mentioning the case of India as an example of such a “hybrid” regime.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05