When the Office of the Economic Adviser in the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) released the data last week, it declared that the wholesale inflation rate had zoomed to 14.23% in November. In other words, wholesale prices in November this year were 14.23% higher than wholesale prices in November last year.

What alarmed many is not just that November is the 8th straight month when wholesale inflation has grown by double digits but also the fact that the latest print is the highest year-on-year increase recorded in any month since the start of the 2011-12 data series.

Many of you might be wondering why aren’t India’s policymakers looking as concerned as you.

For instance, when the Department of Economic Affairs within the Finance Ministry detailed the inflation situation in the country in its “Monthly Economic Review” for November, it largely focussed on the trend in retail inflation — or the inflation rate at the level of retail consumers — and even appeared to give itself a pat on the back when it stated: “inflation continued to remain well ensconced within the policy target band, for four months in a row, reflecting careful macroeconomic management.”

It further assured readers that there was no need for alarm: “Government has been monitoring price situation of major essential commodities on a regular basis and doing needful interventions.”

When it came to discussing the trend in wholesale inflation rate its commentary appeared a tad indifferent — note the use of “may be” — in comparison:

Story continues below this ad

“Wholesale inflation climbed up to 12.5 per cent in October, compared to 10.7 per cent in the previous month. This may be attributed primarily to rise in prices of mineral oils, basic metals, food products, crude petroleum & natural gas, chemicals and chemical products etc. in the month compared to corresponding month of the previous year. The elevated prices in manufacturing component may be ascribed to rising input inflation and calibrated increase in prices by manufacturers.”

It is not just the policymakers within the government who prefer to focus on retail inflation but also the ones at the RBI.

The RBI, which is India’s central bank charged with the mandate to maintain stable prices in the country, also chooses to “target” retail inflation instead of wholesale inflation. And since retail inflation rates have been well contained over the past few months, the RBI, too, sounded rather “dovish” about inflation risks in its latest policy review that was announced on 8th December.

The RBI, which is India’s central bank charged with the mandate to maintain stable prices in the country, also chooses to “target” retail inflation instead of wholesale inflation. And since retail inflation rates have been well contained over the past few months, the RBI, too, sounded rather “dovish” about inflation risks in its latest policy review that was announced on 8th December.

So it is natural to ask: Why do Indian policymakers prefer to target retail inflation instead of wholesale inflation? Wouldn’t a high wholesale inflation rate lead to higher retail inflation? If so, how quickly would that happen?

Story continues below this ad

To understand the answers to any of these questions we must begin by noting how wholesale and retail inflation rates are different from each other.

The wholesale and retail (consumer) inflation rates are based on the wholesale price index (WPI) and the consumer price index (CPI), respectively. In other words, we make two separate indices — one each for wholesale prices and retail prices — and see how the index values have gone up in a particular month as against the index value in the same month last year. The percentage change is the rate of inflation. The CPI-based inflation data is compiled by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (or MoSPI) and the WPI-based inflation data is put together by DPIIT.

The tables alongside detail how the two indices — WPI and CPI — differ in their composition. There are two key differences.

Table 1: Composition of Wholesale Price Index

| Component |

Weight (in %) |

Inflation rate (in %);

Nov 2021 |

| All Commodities |

100.00 |

14.23 |

| Primary Articles |

22.62 |

10.34 |

| Fuel & Power |

13.15 |

39.81 |

| Manufactured Products |

64.23 |

11.92 |

One, if one looks at the weights assigned to different sub-components, it is clear that WPI is dominated by the prices of manufactured goods while CPI is dominated by the prices of food articles. As such, if the year-on-year increase in the prices of food articles is subdued, as is the case at present, chances are that the overall (also called headline) retail inflation will be within reasonable bounds.

Story continues below this ad

In WPI, if manufactured products are getting costlier at the wholesale level then that would likely spike wholesale inflation regardless of how food prices are doing at the wholesale level.

Table 2: Composition of Consumer Price Index

| Component |

Weight (in %) |

Inflation rate (in %);

Nov 2021 |

| General Index |

100.00 |

4.91 |

| Food and beverages |

45.86 |

2.60 |

| Pan, tobacco and intoxicants |

2.38 |

4.05 |

| Clothing and footwear |

6.53 |

7.94 |

| Housing |

10.07 |

3.66 |

| Fuel and light |

6.84 |

13.35 |

| Miscellaneous (services) |

28.32 |

6.75 |

Two, WPI does not take into account the change in prices of services. But CPI does. If services such as transport, education, recreation and amusement, personal care etc. get significantly costlier, then retail inflation will rise but there will be no impact on wholesale price inflation.

Because these two inflation rates are calculated based on two significantly different indices, it is not uncommon to find them at considerable variance with each other as is the case at present. If one looks at the chart below (sourced from the same November review of DEA), it is clear how, over the past two years, the wholesale inflation rate has varied far more than the retail inflation rate.

The wholesale inflation rate has varied far more than the retail inflation rate.

The wholesale inflation rate has varied far more than the retail inflation rate.

In fact, exactly two years ago wholesale inflation was at a 40-month low — growing at barely 0.2% in October 2019 — while the retail inflation rate was at a 16-month high. Similarly, the two inflation rates started diverging between 2012 to 2015. By October 2015, wholesale inflation was negative — that is, actual wholesale prices were declining — while retail inflation was over 7 per cent.

Story continues below this ad

The question remains: Why do policymakers prefer targeting retail inflation instead of wholesale inflation rate?

This is especially so since the RBI, as the monetary authority, has little ability to control food and fuel prices, which together account for well over 50% of the CPI. For instance, raising the repo rate — that is the interest rate at which RBI lends money to the banks — is unlikely to contain the price of vegetables (say onions and/or tomatoes) if unseasonal rains or supply disruptions have led to a sudden spike.

Yet, when, in January 2014, an expert committee of the RBI submitted its report on the ways to revise and strengthen the monetary policy framework in India, it chose to target retail inflation.

Here’s why.

Firstly, the committee pointed out that wholesale inflation “does not capture price movements in non-commodity producing sectors like services, which constitute close to two-thirds of economic activity in India”. This corresponds to the point made earlier about how WPI and CPI are different.

Story continues below this ad

Secondly, it pointed out that wholesale inflation “does not generally reflect price movements in all wholesale markets”. This happens because price quotations for some important commodities such as milk, LPG etc. are taken from retail markets.

Thirdly, movements in WPI often reflect large external shocks and as such, the wholesale inflation rate is often subject to large revisions.

Crowd at a Sunday market in Jammu. (AP)

Crowd at a Sunday market in Jammu. (AP)

For instance, between January 2010 and October 2013, WPI inflation was revised 43 times; on 36 times in the upward direction. “These revisions are made two months after the first announcement, generating large uncertainty in the assessment of inflation conditions. Conducting monetary policy based on provisional numbers generally entails the risk of under-estimating inflationary pressures, especially when inflation is rising,” noted the expert panel which was led by Urjit Patel, who served as the RBI Governor between 2016 and 2018.

Apart from these arguments against the use of WPI-based inflation, the committee gave several arguments in favour of CPI-based inflation as well.

Story continues below this ad

The first advantage is that “the choice of CPI establishes ‘trust’ viz., economic agents note that the monetary policy maker is targeting an index that is relevant for households and businesses.” That’s because the true inflation that consumers face is in the retail market. It is for this reason, noted the committee, that almost all central banks in Advanced Economies and Emerging Market Economies use CPI as their primary price indicator. In other words, since most people use retail inflation as a way to arrive at their real earnings, and use it for wage negotiations etc., it makes more sense for policymakers to target controlling retail inflation rate.

A crucial reason why CPI-based inflation could not be ignored is the fact that it has almost 57% dominance of food and fuel prices. These two types of prices are the most important in shaping people’s expectations of future inflation rates. For policymakers, the present-day inflation rate is less important while people’s expectation of what inflation would be in the future — three months ahead or one year ahead — is more important. That’s because monetary policy tweaks— say, raising or reducing the repo rate — take their time (e.g. a few months) to show impact. Moreover, if people continue to expect high inflation in the future, it impacts their behavior such as their demand for wages etc. This, in turn, reinforces a cycle where firms expect to pay higher wages in the future and thus raise prices, which further reinforces higher inflation expectations among people.

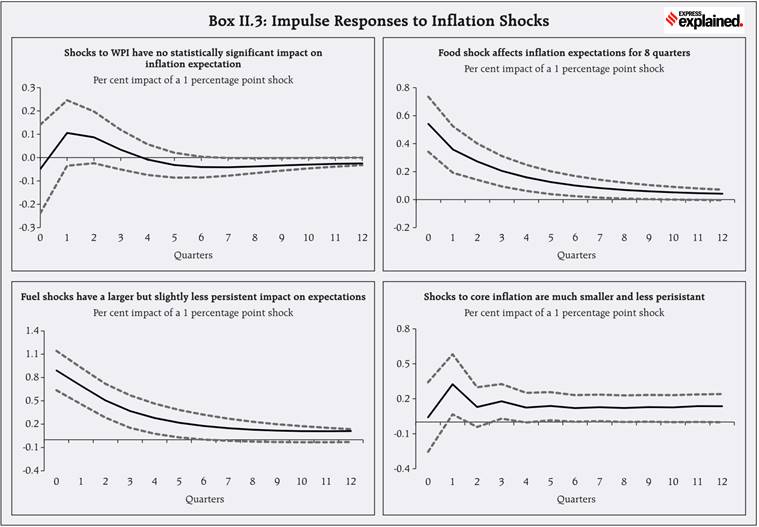

The committee also found that “shocks to food inflation and fuel inflation also have a much larger and more persistent impact on inflation expectations than shocks to non-food non-fuel inflation”. As such, it argued, any attempt to anchor inflation expectations cannot ignore shocks to food and fuel.

Specifically, a 100 basis points (bps) shock to food inflation immediately affects one-year forward expectations by as much as 50 bps and persists for 8 quarters (see the chart below). In other words, if the rate at which food prices rise goes up from 5% last year to 6% this year then people’s expectation of what the inflation rate would be going forward spikes by half-a-percentage point and this effect lingers on for 2 full years.

Story continues below this ad

Impulse responses to inflation shocks

Impulse responses to inflation shocks

In sharp contrast, “shocks to WPI inflation have no statistically significant impact on inflation expectations.” It stands to reason then: Why bother targeting WPI if its links to inflation expectations are weak?

“Therefore, in spite of the argument made that a substantial part of CPI inflation may not be in the ambit of monetary policy to control, the exclusion of food and energy may not yield ‘true’ measure of inflation for conducting monetary policy,” it stated.

So that explains why Indian policymakers — whether they sit in the Finance Ministry or the RBI — care more about what happens to retail inflation than wholesale.

But wouldn’t high wholesale inflation have any impact on retail inflation? If so, over what time period?

Before we look at what the empirical studies in the Urjit Patel committee report showed, just look at the most recent evidence. Since April this year, wholesale price inflation has been running in double digits. The retail inflation rate has been largely stagnant and within control over the last four months.

Of course, there are many factors involved. Low base effect, for instance. A big reason why WPI-inflation has been high in 2021 is the low base since April. That’s because, between April and September 2020, wholesale price inflation was quite muted thanks to the Covid-induced disruptions.

Before April 2021, by contrast, WPI inflation was muted while CPI inflation kept surging even during the pandemic.

However, here’s something more robust. The Urjit Patel committee analysed the relationship between WPI and CPI based on monthly data from January 2000 to December 2013 — a total of 14 years.

When they looked at the impact of an increase in WPI-food inflation on CPI food inflation, they found it to be “significant” and stated that higher food inflation in wholesale markets leads to an increase in retail food inflation “till two months”. An increase in retail food inflation leads to a corresponding increase in WPI-food inflation.

When the committee removed the food and fuel price components from both wholesale and retail inflation rates — thus comparing only the “core” wholesale and retail inflation rates — they found no significant impact of a spike in WPI-Core on CPI-Core and vice versa.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

Next Monday will be the last ExplainSpeaking of 2021 and, as such, will attempt to provide a brief history of the Indian economy as it unfolded this year. If you are new to ExplainSpeaking and enjoy reading it, the next edition might provide a decent opportunity to catch up on 2021.

In the meantime, please continue to share your views and queries with me at udit.misra@expressindia.com. They help me immensely.

Stay masked and stay safe.

Udit

The wholesale inflation rate has varied far more than the retail inflation rate.

The wholesale inflation rate has varied far more than the retail inflation rate. Crowd at a Sunday market in

Crowd at a Sunday market in  Impulse responses to inflation shocks

Impulse responses to inflation shocks