On Monday, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2021 — often incorrectly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics — to three US-based economists. One half of the award has gone to David Card, who teaches at the University of California at Berkeley, and the other half jointly to Joshua D Angrist of MIT and Guido W Imbens of Stanford University. The prize money of 10 million Swedish kronor (Rs 8.60 crore) will be divided accordingly. Imbens, who answered the call from the Academy, was particularly thrilled to have received the award along with his long-time friends; he was not only Imbens’s PhD supervisor but also the best man at his wedding.

Cause & effect

The citation states: “This year’s Laureates have provided us with new insights about the labour market and shown what conclusions about cause and effect can be drawn from natural experiments. Their approach has spread to other fields and revolutionised empirical research.”

To understand, one needs to look at some of the most important questions in society today: Does immigration affect salaries and employment levels? Do investments in school education improve the future earnings of students? Will raising minimum wages lead to lower employment levels?

All these questions have been relevant and continue to be so across time and geographies. But what is particularly tricky about answering any such question is the inability to create a randomised control trial wherein one deprives some kids of school education and provides it to others to ascertain the answer.

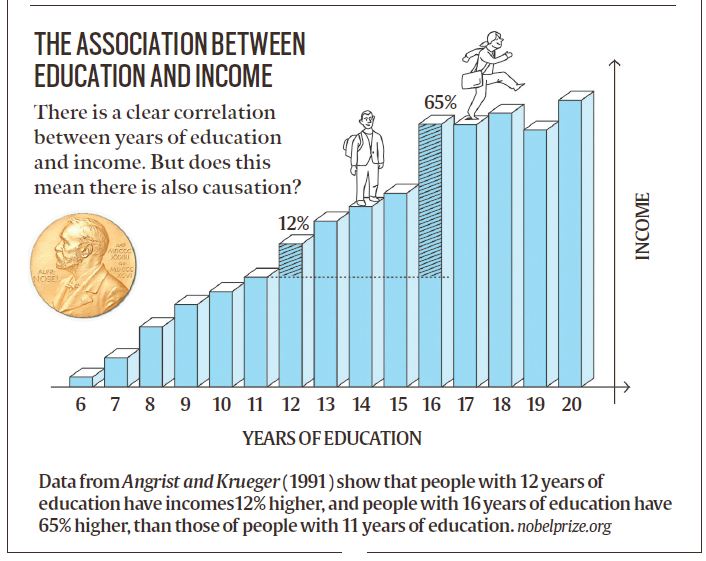

This is where this year’s winners stood out. They found ways to cut through the often observed correlations and established whether or not they exhibited causality. To be sure, correlation is simply the occurrence of two events together, but mere correlation does not imply causality (which requires a clear understanding that one event “causes” the other.)

The association between education and income

The association between education and income

Card: wages & jobs

Story continues below this ad

Card’s use of so-called “natural experiments” (situations arising in real life that resemble randomised experiments) has been both revealing and exemplary.

For example, it is commonly held that raising minimum wages lead to lower employment. The argument is that higher wages will increase costs for the firms and lead to employers recruiting fewer people. But is it the case that higher wages “cause” employment to fall? Or, is it the case that just because the two things have been seen to occur on several occasions, one has, incorrectly, started believing that higher wages lead to lower employment?

Card used a “natural experiment” to test out this presumed casualty. In 1992, the hourly minimum wage in New Jersey was increased from $4.25 to $5.05. Card, along with Alan Krueger, studied the effect on employment in New Jersey and compared it with employment in neighbouring areas of eastern Pennsylvania. “The results showed, among other things, that increasing the minimum wage does not necessarily lead to fewer jobs,” noted the Royal Swedish Academy. Card’s “studies from the early 1990s challenged conventional wisdom, leading to new analyses and additional insights,” they state.

Angrist, Imbens: education, pay

Story continues below this ad

Angrist and Imbens have been recognised “for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships”. They helped make sense of the data from such natural experiments. This is crucial because unlike a clinical trial or randomised control trial, in a natural experiment a researcher is not in control of the experiment. making it difficult to draw precise conclusions and firm up causal links.

For example, extending compulsory education by a year for one group of students (but not another) may or may not affect everyone in the groups in the same way. “Some students would have kept studying anyway and, for them, the value of education is often not representative of the entire group. So, is it even possible to draw any conclusions about the effect of an extra year in school?” the Academy notes. “In the mid-1990s”, the duo “solved this methodological problem, demonstrating how precise conclusions about cause and effect can be drawn from natural experiments.”

The India context

The methodology, research and findings of these economists date back to the early and mid-90s and they have already had a tremendous influence on the research undertaken in several developing countries such as India.

Story continues below this ad

For instance, in India, too, it is commonly held that higher minimum wages will be counterproductive for workers. It is noteworthy that last year, in the wake of the Covid-induced lockdowns, several states, including Uttar Pradesh, had summarily suspended several labour laws, including the ones regulating minimum wages, arguing that such a move will boost employment.

Leading labour economists such as Professor Ravi Srivastava, Director of Centre for Employment Studies in Institute for Human Development, and Radhicka Kapoor, Fellow at the Indian Council for

Research on International Economic Relations, had argued against such deregulation last year.

“Their studies did provide a justification for raising minimum wages in the US — a question on which the economics fraternity was very divided. I used it with other studies to justify a national minimum wage for India,” said Srivastava.

Story continues below this ad

Kapoor said the main learning from Card’s work is that minimum wages can be increased in India without worrying about reducing employment. She pointed out that minimum wages in India are very low. The national minimum wage, for instance, is just Rs 180 per day.

Now, India has a minimum wages code; it will extend to unorganised sector workers. “So, enhancing minimum wages is very important to improve incomes in the unorganised sector as well,” she said. “This (learning that raising minimum wages do not hold back employment) is particularly important given the aggregate demand constraints that exist in the Indian economy, especially among those who are at the bottom of the income distribution”.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

The association between education and income

The association between education and income