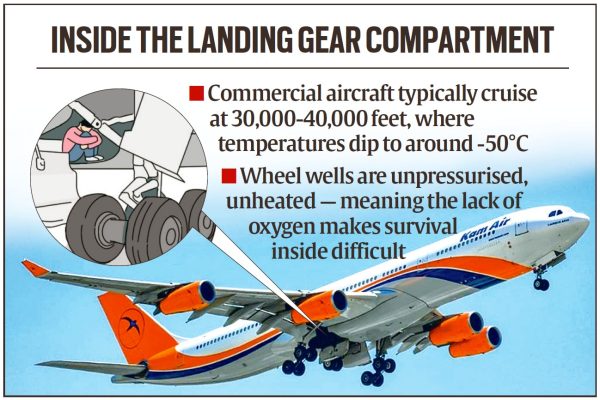

Sneaking into an aircraft wheel well and travelling secretly as a stowaway is an extremely dangerous thing to do, with the odds heavily stacked against survival. Yet, such incidents keep surfacing from time to time, often involving the tragedy of the loss of human life. Nonetheless, occasionally, wheel-well stowaways — those who try to travel in the unpressurised and unheated wheel well or landing gear compartment — survive miraculously. One such incident happened just last Sunday on a flight from Afghanistan to India.

A 13-year-old boy from Kunduz, Afghanistan, wanted to travel to Iran. So, he managed to sneak into an aircraft’s rear wheel well at the Kabul airport, except that the plane — operating Kam Air flight RQ4401 — was bound for Delhi, not Tehran. For the flight duration of over 90 minutes, the boy was in the wheel well, even as the aircraft cruised at over 30,000 feet where outside air pressure and temperature plummet. Miraculously, he survived the ordeal, landing seemingly unharmed at the Delhi airport, where he was spotted by some airport staff. In the evening, he was sent back on the same aircraft to Kabul, this time in the plane’s passenger cabin.

As adventurous as the Afghan teen’s one-day sojourn might sound, it was one fraught with extreme danger, and is something that should never be attempted. The fact that he survived must be seen as an exception, for a rather grim outcome is the norm. Unsurprisingly, given the risks involved, wheel-well stowaways largely come from regions grappling with poverty, conflict, or instability, and are desperate to escape in search of better opportunities. Often, they are not aware of the perils of embarking upon such a journey. In rare cases, wheel-well stowaways may just be thrill-seekers.

Hard to survive: what the data show

According to US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) data, 132 people tried to travel in the landing gear compartments of commercial aircraft between 1947 and 2021. Thereafter, incidents of eight more people trying to travel this way have come to light; only two of the eight survived. The mortality rate for wheel-well stowaways is estimated at around 77 per cent. Apart from hypoxia due to lack of sufficient oxygen and hypothermia due to temperatures as low as minus 65 degrees celsius, the chances of fatal injury by the movement of the landing gear as well as the risk of falling out are quite high.

It is highly likely that the survival rate may be even poorer than what the data show. A number of unsuccessful attempts might have not come to light as the bodies may have fallen into an ocean or a remote land area. On the other hand, a few successful attempts might have remained unknown as with survivors managing to escape from the destination airport without detection. But incidents involving well-wheel stowaway are not quite frequent, partly due to strict airport security in most parts of the world.

Inside the wheel well of an aircraft

Inside the wheel well of an aircraft

The only known incident involving Indian wheel-well stowaways dates back nearly 30 years to 1996. Brothers Pradeep Saini and Vijay Saini managed to get into the wheel well of a British Airways Boeing 747 aircraft operating a flight from Delhi to London. Pradeep survived the long-haul flight, but Vijay didn’t.

Researchers have concluded that to gain access to the aircraft, the typical stowaway would hide near the point where the departing plane waited at the runway for takeoff clearance. While the plane was stationary, the stowaway would mount a landing gear and climb into a wing recess area adjacent to where the wheel would retract. Large aircraft generally have enough space in the landing gear compartment for a short and lean person to crawl into the space and hide.

Story continues below this ad

Havoc on the human body makes survival rare

While the metal covers over the landing gear compartment provide a degree of safety — mainly from falling off — once the aircraft has taken off and the wheels have retracted, they don’t really protect the stowaway from the two biggest and imminent threats—hypoxia and hypothermia. Hypoxia is caused by inadequate oxygen, while hypothermia is a fall in core body temperature to a level where normal physical and brain functions are impaired. Severe levels of either can lead to unconsciousness, and even death.

At extremely high altitudes of over 30,000 feet where commercial aircraft cruise, air pressure is extremely low and temperatures frigid. The aircraft cabin is pressurised and a comfortable temperature is maintained. The wheel well, however, is not pressurised and has hardly any protection against outside temperature at high altitudes. As the aircraft climbs, a few heat sources — tire friction, warm hydraulic fluid, ambient heat — inside the wheel-well compartment may, for a short while, help delay the onset of hypothermia. But as the aircraft gains altitude, any heat from these sources diminishes rapidly.

According to a 1997 issue of an aviation medicine publication by the US-based Flight Safety Foundation (FSF), the physiological effects experienced by stowaways are minimal at altitudes of up to 2,440 meters, or 8,000 feet. But breathing rate begins to pick up at this point as the oxygen level in the blood drops to about 92 per cent from the sea level average of about 97 per cent.

At 15,000 feet, the wheel-well stowaway’s reaction time would slow by as much as 50 per cent. At 18,000 feet, the breathing rate would rise by about 65 per cent to make up for the lack of oxygen, and several visual and cognitive symptoms of hypoxia would appear, including weakness, light-headedness, confusion, degradation in colour and peripheral vision, tremors, and slurring of speech, among others, the FSF publication said.

Story continues below this ad

Then, at around 22,000 feet, the stowaway, if unacclimated to living in high-altitude regions, would be able to barely maintain consciousness as the blood oxygen level would have crashed to around 50 per cent, which would most likely cause unconsciousness in six minutes or less, the publication noted. At cruising altitudes—over 30,000 feet—the blood oxygen levels are lower than what is required to support brain consciousness.

At the stage of mild hypothermia, there is shivering. In the moderate stage, there are violent shivers as the body’s core temperature drops by 3 degrees celsius, and is accompanied with some conditions similar to hypoxia, like slurred speech and irrational behavior. In severe hypothermia, there is shivering in violent waves. The shivering would eventually cease if the body’s core temperature slips below 33 degrees celsius, or 92 degrees fahrenheit, as it won’t be sufficient to neutralise the drop in body temperature.

If it comes to that, the stowaway will require medical assistance to recover. At this stage, muscle rigidity builds, pupils dilate, and the pulse rate falls. Body temperature in hypothermia can fall to 27 degrees Celsius (81 degrees Fahrenheit) or even lower. Apart from hypoxia and hypothermia, stowaways risk developing decompression sickness and nitrogen gas embolism—the sudden obstruction of a blood vessel.

Only the fortunate survive

According to a 1996 report by the US FAA’s Civil Aeromedical Institute (CAMI), to survive severe hypoxia, physiologic control mechanisms place the body into what is known as the “poikilothermic” state, which is similar to hibernation. In this state, the body’s oxygen requirement diminishes significantly, and it curls into a fetal position to conserve heat. The heart rate may fall to just two beats per minute and breathing rate as low as once in 30 seconds. But the stowaway has to be incredibly lucky to get into this state.

Story continues below this ad

“As a wheel-well stowaway is carried to lower altitudes, a gradual rewarming occurs, along with reoxygenation. If the individual is so fortunate as to avoid brain damage or death from the hypoxia and hypothermia, cardiac arrest or failure on rewarming, or severe neurovascular DCS complications, some progressive recovery of consciousness occurs, perhaps in the period before landing, or at a time after landing. Survival is jeopardized if the recovering stowaway begins moving round and falls out when the landing gear is lowered,” the CAMI report noted.

But even those who may survive the perilous journey in the wheel well of an aircraft may not be completely unscathed, and could carry the scars in the form of physiological damage, like hearing loss and frostbite injuries, among others, and even psychological trauma.

Inside the wheel well of an aircraft

Inside the wheel well of an aircraft