Who was Kesvananda Bharati and how was he associated with the ‘Basic Structure’ doctrine?

As Vice President Dhankar rekindled the debate over the “Basic Structure” doctrine, we take a look at Kesavananda Bharati, the man whose court case resulted in the the Supreme Court’s landmark verdict regarding it

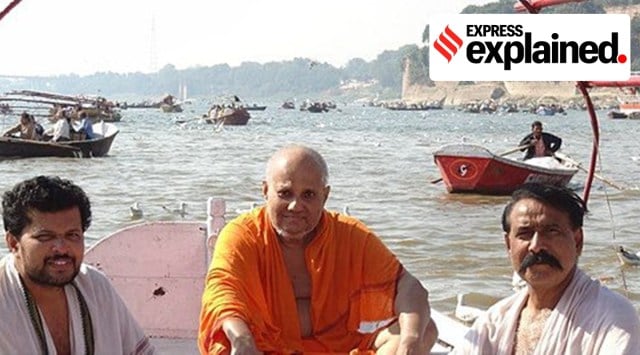

Born in 1940, Kesavananda Bharati took sanyas at the age of 19 and headed to the Edneer Mutt, a Hindu monastery in Kasargod, Kerala. In 1961, still only 21, he was appointed as the head of the Mutt, a position he held till his death in 2020.

Born in 1940, Kesavananda Bharati took sanyas at the age of 19 and headed to the Edneer Mutt, a Hindu monastery in Kasargod, Kerala. In 1961, still only 21, he was appointed as the head of the Mutt, a position he held till his death in 2020.

On Wednesday, in his inaugural address at the 83rd All-India Presiding Officers Conference in Jaipur, Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar again raised the issue of the powers of the judiciary vis-a-vis the legislature, highlighting the 2015 decision of the Supreme Court to strike down the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act.

“Parliamentary sovereignty and autonomy cannot be permitted to be qualified or compromised as it is quintessential to survival of democracy,” he said.

The Vice President’s remarks slammed the Supreme Court’s landmark 1973 judgement in the Kesavananda Bharati case in which it ruled that Parliament had the authority to amend the Constitution but not its basic structure. “With due respect to the judiciary, I cannot subscribe to this (that parliament cannot amend the basic structure),” Dhankar said.

While the verdict and the basic structure doctrine are well known, less has been said about the man whose court case resulted in the Supreme Court’s landmark judgement that established the basic structure doctrine.

The Indian Express takes a look at Kesavananda Bharati and how a seer from Kerala “saved the Indian constitution.”

A monk from Adi Shankaracharya’s tradition

Born in 1940, Kesavananda Bharati took sanyas at the age of 19 and headed to the Edneer Mutt, a Hindu monastery in Kasargod, Kerala. In 1961, still only 21, he was appointed as the head of the Mutt, a position he held till his death in 2020.

A proponent of the Smartha tradition of Advaita Vedanta, at the Mutt, he was referred with his honorific title: Srimad Jagadguru Sri Sri Sankaracharya Thotakacharya Keshavananda Bharathi Sripadangalavaru. The Edneer Mutt is believed to have been established by Totakacharya, one of four original disciples of Adi Shankaracharya, the man credited to have synthesised the non-dualistic philosophy of Advaita Vedanta.

Kesavananda Bharati was known to be a patron of Hindustani and Carnatic music as well as Yakshagana, a folk theatre form popular in some districts of Karnataka and the border district of Kasargod, Kerala.

Fighting against the Kerala government’s land reforms

Kesavananda Bharati did not have any larger, “constitutional” aims when he took the Kerala government to court in February 1970. Rather, he was challenging the 1969 Land Reforms enacted by the communist C. Achuta Menon government which had affected his Mutt. Under the reforms, the Edneer Mutt lost a large chunk of its property, which contributed to its financial woes.

Filing a writ petition in the Supreme Court, Kesavanandas Bharati argued, along with his lawyer Nani Palkhivala, that this action violated his fundamental rights – in particular, his fundamental right to religion (Article 25), freedom of religious denomination (Article 26), and right to property (Article 31).

A monumental case for India’s democracy

The case, Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalvaru and Ors vs State of Kerala and Anr, would go on for over three years with a 13-judge bench hearing the matter. The hearings themselves went on for 68 working days. Alongside Kesavananda Bharati, representatives of coal, sugar and other industries adversely affected by land reforms also presented their sides.

The 13-judge bench concluded with a 7-6 majority that the Constitution’s ‘basic structure’ is inviolable and cannot be altered by the Parliament. While the court itself did not define what this basic structure meant, it cited the following to be included in this basic structure.

The basic structure may be said to consist of the following features:

- Supremacy of the Constitution;

- Republican and Democratic forms of Government.

- Secular character of the Constitution;

- Separation of powers between the Legislature, the executive and the judiciary;

- Federal character of the Constitution.

- The judgement read, “the above structure is built on the basic foundation, i.e., the dignity and freedom of the individual. This is of supreme importance. This cannot by any form of amendment be destroyed.”

Proponents of the basic structure doctrine consider it to be a safety valve against majoritarian authoritarianism. Without it, it is plausible that Indira Gandhi’s 1975 Emergency could have had far more deleterious effects on the health of Indian democracy.

However, opponents claim that the doctrine amounts to judicial overreach over the legislature – something that itself is undemocratic.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05