Trump dominates NATO summit: 3 takeaways from the meeting

Trump called the summit 'a very historic milestone' as Nato allies made the ambitious 5% GDP defence spending target

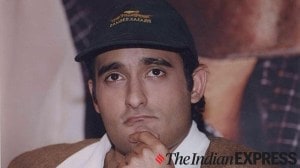

President Donald Trump gestures during a press conference after the plenary session at the NATO summit in The Hague, Netherlands, on Wednesday. (AP Photo)

President Donald Trump gestures during a press conference after the plenary session at the NATO summit in The Hague, Netherlands, on Wednesday. (AP Photo)United States President Donald Trump dominated the discussions during this year’s NATO summit, which concluded on Wednesday (June 25). He returned to Washington after what he saw as a symbolic victory — the NATO members agreement on increasing their defence spending to 5% of their gross domestic product (GDP).

Here are key takeaways from the summit.

The 5% defence spending target

Trump called the summit “a very historic milestone” as Nato allies (the member nations) made the ambitious 5% GDP defence spending target. He said the consensus was “something that no one really thought possible. And they said: ‘You did it, sir, you did it’. Well, I don’t know if I did it … but I think I did.”

Of the 5% figure, 3.5% would be achieved entirely through core defence spending and weapons. The remaining 1.5% can be put towards “defence-related expenditure”, broadly referring to such infrastructural spending to “protect our critical infrastructure, defend our networks, ensure our civil preparedness and resilience, unleash innovation, and strengthen our defence industrial base”.

Allies (NATO members) would need to submit plans to meet the 5% figure annually and follow a “credible, incremental path”, with a review on progress expected after the 2029 US presidential election.

The 3.5% core defence spending target itself will be out of reach for several NATO countries, which have hovered around the previous 2% target. The US spent 3.2% of its GDP on defence spending in 2024, according to NATO estimates. Only three countries exceeded this share – Poland (4.1%), Estonia (3.4%) and Latvia (3.4%).

Spain, which had allocated 1.24% of its GDP in 2024 to defence spending, announced it would not adhere to this target, earning Trump’s ire and the potential for Spain-specific trade sanctions.

Article 5 in the spotlight

Article 5, or the collective defence clause, serves as the bedrock of NATO’s existence. It says an attack against even one of the members would be considered an attack against all members. It also says that in the event of such an attack, each member would individually and collectively take “such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.’’

This “One for All, All for One” principle has helped the organisation attract more members over the years. As the Russia-Ukraine War broke out in 2022, the historically neutral nations of Finland and Sweden made a bid to join it.

During his presidential campaign, Trump revived his criticism of the organisation, saying the US under his presidency would choose not to defend a member under attack if it spends less than the agreed targets. On Wednesday, he was among the NATO allies who underlined their “ironclad commitment” to come to each other’s aid if attacked.

“They want to protect their country, and they need the United States, and without the United States, it’s not going to be the same,” he told reporters. “I left there saying that these people really love their countries. It’s not a rip-off. And we’re here to help them protect their country,” he said.

Focus away from Ukraine

Since 2022, every NATO summit has committed to aiding Ukraine in its war against Russia. Most NATO countries view Russia as a direct and immediate threat. The 2024 summit saw Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy be feted by then-US President Joe Biden and secure an assurance from NATO President Mark Rutte that Ukraine’s path to NATO membership was “irreversible”.

This policy has been largely upended by Trump’s return to the White House this January. Since his first term (2017-21), Trump has remained cordial with Russian President Vladimir Putin, reversing decades-long animosity between the US and Russia. In his second term, the Trump administration has ruled out the possibility of Ukraine joining NATO, lashed out against Zelenskyy for being “ungrateful”, and has paused US military aid to Ukraine in its war against Russia.

This set the stage for the NATO summit, as the Ukraine issue was relegated to the backseat. Unlike last year, when the NATO declaration took note of Russia’s “brutal war of aggression”, the statement this year mentioned “long-term threat posed by Russia to Euro-Atlantic security” without specifically condemning Russia.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05