“Food versus fuel” is a familiar debate in the context of sugarcane, rice, maize, palm or soyabean oil being diverted for the production of ethanol and biodiesel.

But there’s also a looming “food versus cars” dilemma, which is linked to phosphoric acid — the key ingredient in di-ammonium phosphate (DAP), India’s second most consumed fertiliser after urea — increasingly finding its way into the production of batteries for electric vehicles (EVs).

DAP contains 46% phosphorous (P), a nutrient crops need at the early growth stages of root and shoot development. The ‘P’ comes from phosphoric acid, which is manufactured from rock phosphate ore after grounding and reacting with sulphuric acid.

But phosphoric acid is also the source of ‘P’ in lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries. These supplied more than 40% of the global EV capacity demand in 2023 — up from a modest 6% in 2020 — gaining market share from normal nickel-based NMC and NCA batteries.

While all three are lithium ion batteries, the first type uses iron phosphate as the raw material for the cathode or positive electrode; the others use more expensive nickel, manganese, cobalt and aluminium oxides.

Implications for India

India consumes 10.5-11 million tonnes (mt) of DAP annually — next only to the 35.5-36 mt of urea — more than half of which is supplied through imports from China, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Russia, and other countries.

In addition, India imports phosphoric acid (mainly from Jordan, Morocco, Senegal, and Tunisia) and rock phosphate (from Morocco, Togo, Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, and the UAE) for the domestic production of DAP, as well as other P-containing fertilisers.

Story continues below this ad

In 2022-23, India imported 6.7 mt of DAP (valued at $5,569.51 million), 2.7 mt of phosphoric acid ($3,622.98 million) and 3.9 mt of rock phosphate ($891.32 million). These amounted to $10 billion-plus of imports — excluding imports of other inputs, namely ammonia and sulphur/ sulphuric acid.

But just as bio-fuels have created an alternative market for foodgrains, sugarcane, and vegetable oils, merchant-grade phosphoric acid with 52-54% P used in fertilisers is finding new application as cathode raw material in EV batteries after further purification.

This is already being seen in China, where two-thirds of EVs sold in 2023 had LFP batteries. China is a leading DAP supplier to India (Table 1). It was also the world’s third largest shipper of DAP (5 mt) and other phosphatic fertilisers (1.7 mt) in 2023, after Morocco and Russia. As more of China’s phosphoric acid goes towards LFP batteries, there will be that much less available for manufacturing fertilisers — hence the ‘cars vs food’ dilemma.

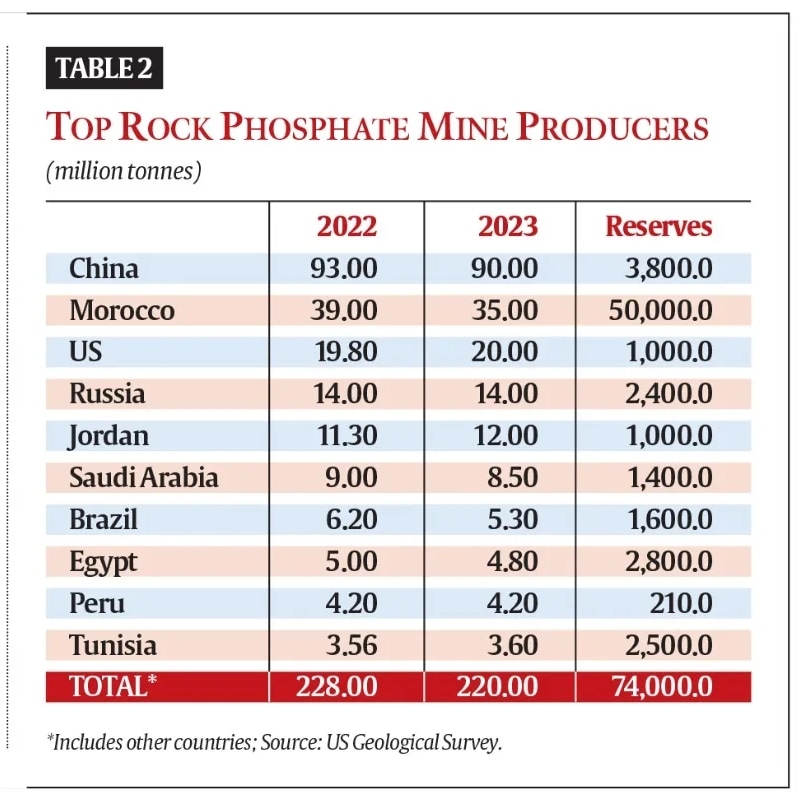

The share of LFP batteries in EV sales is still below 10% in the US and Europe. However, even these markets are likely to switch to batteries that are less dependent on critical minerals such as cobalt — whose world reserves are only 11 mt, of which 6 mt are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Rock phosphate and iron ore reserves are more abundant, at 74,000 mt and 190,000 mt respectively.

The share of LFP batteries in EV sales is still below 10% in the US and Europe. However, even these markets are likely to switch to batteries that are less dependent on critical minerals such as cobalt — whose world reserves are only 11 mt, of which 6 mt are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Rock phosphate and iron ore reserves are more abundant, at 74,000 mt and 190,000 mt respectively.

Story continues below this ad

The lower cost apart, LFP batteries score in longevity (chargeable more number of times) and safety (less overheating/ fire risk), offsetting their disadvantage of lower energy density (larger size required to store the same amount of energy).

The looming challenge

As the world moves more to LFP batteries, it can potentially reduce the supply of phosphate fertilisers. India’s DAP imports of 1.59 mt during April-August 2024 were 51% below the 3.25 mt for the same period of last year. This was largely due to export restrictions imposed by China.

While China is the only country that is mass-producing LFP batteries now, Morocco too has attracted significant investor interest for establishing LFP cathode materials and EV battery manufacturing facilities. The North African nation is the second biggest rock phosphate miner after China, but holds an estimated 50,000 mt or nearly 68% of global reserves (Table 2).

With phosphate reserves of hardly 31 mt and an annual production of 1.5 mt, India has to meet the bulk of its nutrient requirement (including as intermediate acid and finished fertiliser) from suppliers such as Morocco’s OCP Group, Russia’s PhosAgro, and Saudi Arabia’s SABIC and Ma’aden.

Story continues below this ad

This also makes India vulnerable to changing global market dynamics — whether on account of war-induced supply shocks, or the diversification of phosphoric acid use beyond fertilisers.

Way forward for India

The effects of low DAP imports may be felt in the ensuing rabi (winter-spring) crop season, starting with mustard, potato and chana (chickpea) plantings in October and wheat in November-December. Farmers apply this fertiliser, necessary for root establishment and growth, right at the time of sowing.

Sales of DAP fell 20.5% even during the kharif (monsoon) season, from 4.83 mt in April-August 2023 to 3.84 mt in April-August 2024. It was partly compensated by a 29.5% jump in that of complex fertilisers — containing nitrogen (N), P, potassium (K), and sulphur (S) in different combinations — from 4.55 mt to 5.88 mt.

Farmers basically replaced DAP (which has 46% P plus 18% N) with complexes having less P (the likes of 20:20:0:13, 10:26:26:0 and 12:32:16:0). They may have to do the same in the coming rabi.

Story continues below this ad

The decline in DAP imports and sales has been exacerbated by government policy fixing its maximum retail price (MRP) at Rs 27,000 per tonne. This is only marginally more than the Rs 24,000-26,000 for 20:20:0:13 (having less than half DAP’s P content) and less than the Rs 29,400 for 10:26:26:0 and 12:32:26:0.

Fertiliser companies are currently being paid a subsidy of Rs 21,676, average rail freight reimbursement of Rs 1,700 and, more recently, a one-time special incentive of Rs 3,500 on DAP sales. Adding these to the MRP of Rs 27,000 takes their overall realisation to Rs 53,876 per tonne.

As against this, the landed price of imported DAP is around $620 per tonne. Together with other expenses (5% customs duty, port handling, bagging, freight, interest, insurance, dealer margins, etc), the total cost comes to roughly Rs 61,000 per tonne.

Thus, companies are incurring a loss of more than Rs 7,100 per tonne, making it unviable to import and market DAP. They are, instead, choosing to sell complexes or single super phosphate containing just 16% P and 11% S.

Story continues below this ad

This may not be a bad thing. A country having very little rock phosphate, potash, sulphur, and natural gas reserves cannot afford to consume too much DAP, urea (46% N), and muriate of potash (60% K). The future lies more in fertiliser products incorporating less N, P, K, and S, but having higher nutrient use efficiency.

In the long run, India needs to also secure supplies of raw materials, especially phosphates, through overseas joint ventures and buy-back arrangements. Indian companies already have four plants manufacturing phosphoric acid in Senegal, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia. More are probably required.

The share of LFP batteries in EV sales is still below 10% in the US and Europe. However, even these markets are likely to switch to batteries that are less dependent on critical minerals such as cobalt — whose world reserves are only 11 mt, of which 6 mt are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Rock phosphate and iron ore reserves are more abundant, at 74,000 mt and 190,000 mt respectively.

The share of LFP batteries in EV sales is still below 10% in the US and Europe. However, even these markets are likely to switch to batteries that are less dependent on critical minerals such as cobalt — whose world reserves are only 11 mt, of which 6 mt are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Rock phosphate and iron ore reserves are more abundant, at 74,000 mt and 190,000 mt respectively.