Click for more updates and latest Hollywood News along with Bollywood and Entertainment updates. Also get latest news and top headlines from India and around the World at The Indian Express.

View from the Side Window

American filmmaker Cary Joji Fukunaga talks about the making of Beasts of No Nation, his upcoming projects, and why adaptation is a tricky business

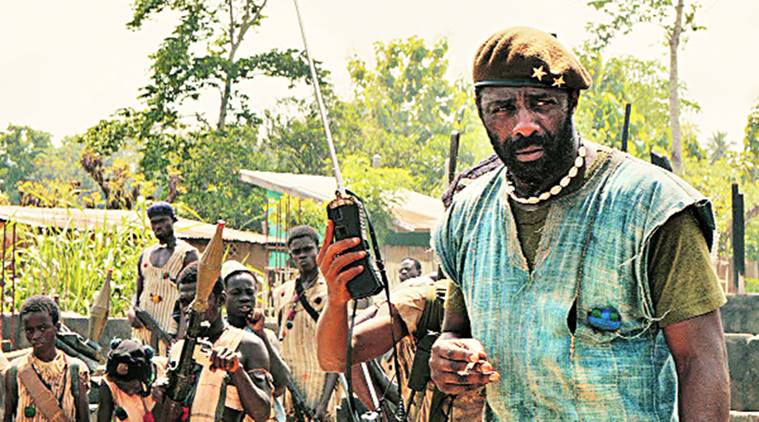

Stills from Beasts of No Nation

Stills from Beasts of No Nation

A BEER in the afternoon is a handy pick-me-up for Cary Joji Fukunaga, who hasn’t slept much since he landed in the Subcontinent two weeks ago. “I’m not jetlagged but I went to Bhutan for a six-day trek. It was insane and a lot of fun. I got back to Delhi and then left to tour Kerala and Tamil Nadu, and now I’m in Mumbai and I just want to sleep,” he says. Fat chance. Fukunaga, 39, is attending the 18th JIO MAMI Mumbai Film Festival, where his sessions are already sold out.

Watch What Else is Making News

If his name doesn’t sound familiar in the beginning, one only has to mention that he directed the first season of HBO’s True Detective (2014). Many people at MAMI keep bringing up the single-take action sequence in the fourth episode — the scene is a breathless charge of energy and violence that has spawned an almost instant fandom online for Fukunaga. But it’s hardly the toughest shoot that the American filmmaker has experienced. That honour goes to his last film, Beasts of No Nation (2015), a coming-of-age story of a child soldier when civil war breaks out in an unnamed West African country.

Still form True detective (left), and Jane Eyre (Right)

Still form True detective (left), and Jane Eyre (Right)

“Since 1999, I wanted to make a film about a child soldier; the imagery drew me. When I was applying to film school in the New York University, my feature project was on that subject. I went to Sierra Leone and did some research and started fermenting ideas of what this could be,” says Fukunaga. A friend at the Peace Corps gave him Uzodinma Iweala’s novel, Beasts of No Nation, but it would take Fukunaga nearly 10 years to adapt the film for the big screen. “Just getting the film to Ghana was so difficult, we called it ‘Operation Blackstar’, from the black star on the Ghanian flag,” he says.

He first wrote and directed Sin Nombre (2009), a Spanish-language thriller about a Honduran girl who tries to migrate to the US. Fukunaga’s debut was met with critical acclaim and the next few years saw him juggle multiple mediums — not just full-length features such as Jane Eyre (2011) but also projects such as Sleepwalking in the Rift (2012), a short film made for Maiyet, the NYC-based fashion label. “They asked me if I could come up with a story, and that it would be shot in Kenya. I just had two weeks to figure it out,” he says. The commercial is lush with colour, Masai tribesman, and animals in the Kenyan savannah. But Fukunaga’s masterful use of silence elevates the commercial to being more than an exercise in artistic capitalism. “I find sound very interesting. If there’s bad sound, you can’t sit through the film,” he says.

In the beginning of his career, Fukunaga worked as a camera operator, and constantly draws upon that experience. “I like to set a frame and not pan it even if somebody is moving around. The best blocking is about finding ways to play within the confines. Take Abbas Kiarostami’s A Taste of Cherry, for example, when you’re just looking at people through the side window of the car. How does that limitation create an interesting revealing of information? It’s like how photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson tell a story in a single frame,” he says.

Fukunaga is now adapting a few books, namely A Soldier of the Great War by Mark Helprin, and Tom Reiss’s The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo into screenplays. Adaptations are a tricky business, he says, as the conversation veers to Anthony Minghella’s adaptation of The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje — a film that didn’t stay true to the book. “I haven’t read the book but the parts with Ralph Fiennes are more interesting than what happens to Kip, which is where I feel the film slows down. But here’s the thing, and I felt this with Jane Eyre — in a book, your emotional and psychological experience with a character is more intimate than it can ever be in a movie. As a director, all you’re doing is trying to immerse your audience into the story, whereas in a novel, it’s being piped right into you,” he says.

If there’s one question Fukunaga isn’t quite prepared for, it’s the one about Indian films. “I haven’t watched as many as I would have liked, but I hope to get to know about some,” he says, while writing down suggestions on the back of his hand.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05