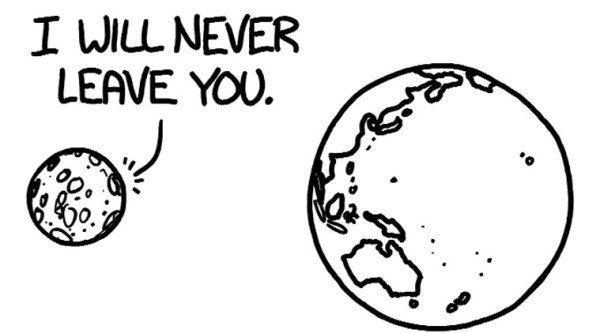

What if?

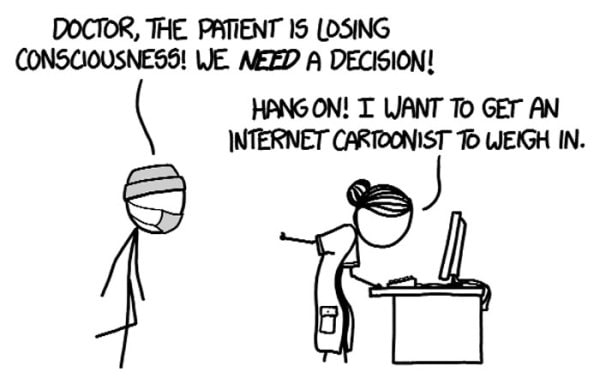

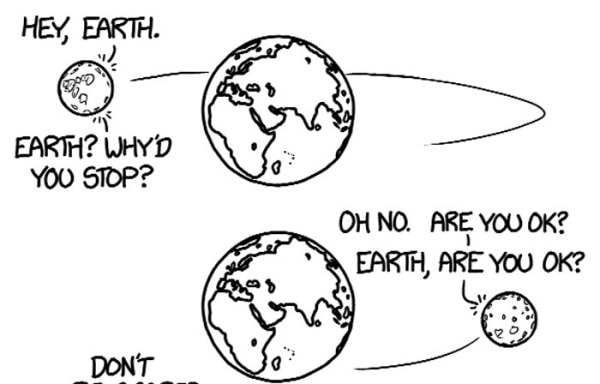

Randall Munroe, the creator of the Web comic xkcd, explains complexity through absurdity.

Randall Munroe, the creator of the Web comic xkcd, explains complexity through absurdity.

Randall Munroe, the creator of the Web comic xkcd, explains complexity through absurdity.

While giving a physics talk for high school students five years ago at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Randall Munroe could tell that his audience was, in his words, “not totally with me”.

He was trying to explain potential energy and power — not complex concepts, but abstruse.

So, in the middle of his three-hour presentation, Munroe, who is best known as the creator of the Web comic xkcd, switched gears to Star Wars.

“I thought about the scene in The Empire Strikes Back when Yoda lifts the X-wing out of the swamp,” he said in an interview. “It occurred to me as I was lecturing.”

Instead of abstract definitions (an object lifted upward gains potential energy because it will accelerate if dropped; power is the rate of change in energy), Munroe asked a question: How much Force power can Yoda output?

“And so I did a rough version of the calculation in the classroom, looking up the craft dimensions and measuring things in the scene on the projector in front of them,” Munroe said. “They all perked up.”

For most people, physics is not interesting in itself.

“The tools are only fun when the thing you’re using them on is interesting,” he said.

The students started asking other questions. “What about the end of The Lord of the Rings when Sauron’s eye explodes?” he recalled.

“How much energy is that?”

The experience inspired Munroe to start soliciting similar questions from his xkcd readers.

Munroe has now collected that work, including a version of his Yoda calculations and new material, into a book, What If? which has been on the non-fiction best-seller list since it was published in September.

As its cover asserts, the book is full of “serious scientific answers to absurd hypothetical questions”.

“It exercises your imagination, and his dry wit is charming,” said William Sanford Nye, better known as Bill Nye the Science Guy. “He does, for lack of a better term, absurd scenarios, but they’re instructive.”

Some examples: What would happen if you tried to hit a baseball pitched at 90 per cent the speed of light? “The answer turns out to be a lot of things,” Munroe writes, “and they all happen very quickly, and it doesn’t end well for the batter or the pitcher.”

If every person on Earth aimed a laser pointer at the moon at the same time, would it change colour? “Not if we used regular laser pointers.”

The explanations are accompanied by the same stick-figure drawings and nerdy wit that made xkcd popular. What does xkcd mean? It is meaningless. The comic’s website helpfully explains, “It’s just a word with no phonetic pronunciation.”

As a child, Munroe also asked questions. In the book’s introduction, he recounts wondering if there were more hard things or soft things in the world. The conversation made such an impression on his mother that she wrote it down. Munroe, then 5, had concluded the world contained about 3 billion soft things and 5 billion hard things.

“They say there are no stupid questions,” Munroe, now 30, writes. “That’s obviously wrong; I think my question about hard and soft things, for example, is pretty stupid. But it turns out that trying to thoroughly answer a stupid question can take you to some pretty interesting places.”

Now, he said, he receives thousands of questions a week. Many are obviously students looking for help with homework. Others can be answered simply: No.

“One of them was ‘Is there any commercial scuba-diving equipment that would allow you to survive under molten lava?’” Munroe said. “No, there’s not.”

Once he chooses a question worth answering, he spends a day or two immersing himself in research and then writing. He rarely consults experts, as he is often working at 4 am and “there’s no point in trying to call someone.”

One of his favourite replies, which ends the book, is to a question about earthquakes: “What if a Richter magnitude 15 earthquake were to hit America? What about a Richter 20? 25?”

The answer is that a magnitude 15 earthquake would destroy the planet. “That’s not interesting,” Munroe said. Then he flipped the question around. The scale, which is logarithmic, can also describe smaller rumblings of zero or negative magnitude. A quake of magnitude zero would release one thirty-second the energy of a magnitude 1 quake. Munroe calculated that it would be like the Dallas Cowboys’ running full tilt into a garage. And a magnitude of minus 15 would be a mote of dust landing on a table.

After so many questions involving mayhem and destruction, Munroe said, “It’s nice to leave the world alone and leave it quiet.” (NYT)