Opinion Haldwani demolitions: The State blurs the distinction between legal and illegal — and punishes the poor

There is no public good in ‘bulldozer urbanism’. Demolitions and evictions that mainly affect the poor irreparably damage already vulnerable lives while also failing as public policy

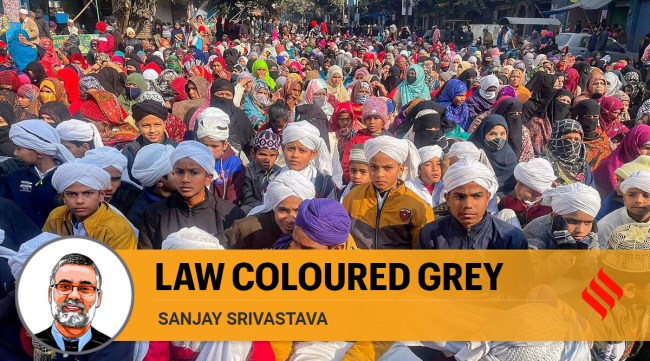

Women and children stage a dharna against the eviction. (Photo: PTI)

Women and children stage a dharna against the eviction. (Photo: PTI) The Supreme Court has stayed the demolition on the railway land in Haldwani where “encroachers” have been asked to vacate the land or face eviction. Regardless of their fate, there is one aspect of this episode we must never forget: That the modern history of land in India is a history of blurred distinctions between illegality and legality that the state itself generates and maintains. It is also a cautionary history of the selective manner in which the state deals with different sections of the population, making democracy a movable feast rather than a consistent system of governance and citizens’ rights.

The Haldwani case is similar to a number of other instances of “encroachments” and demolitions around the country where vast areas of apparently illegal residential and commercial complexes hide in plain sight. That is – notwithstanding the strictures of master plan documents – offices, schools, hospitals, shops and residential structures come to “illegally” occupy lands owned by this or that government authority in full view of the urban life that swirls around them. And then, one day, like some secular magic or act of administrative occultism, the illegality is discovered and, depending on who occupies these lands, removed. However, by this time, the facilitators of the illegality – usually state officials at different levels, have long departed their posts, and transferred to another opportunity elsewhere. This has greater consequences than just the dislocation of lives (it is usually the urban poor who are the most discardable of our populations). It cumulatively institutionalises the illegality that the state nurtures within it and further develops it as a well-crafted art of governance.

There is a relatively long history to this craftiness. In 1951, the government constituted a committee, chaired by the industrialist G D Birla, to inquire into the activities of the colonial-era Delhi Improvement Trust (DIT). The Birla Committee noted that DIT’s strategy of buying land at cheap rates, “freezing” supplies and then selling to the highest bidder had only exacerbated the problems of housing and access to land. This modus operandi also became the norm for DIT’s successor, the state-owned land monopolist, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA). The key point that the Birla Committee sought to make was that illegal urban spaces (its “slums”) were not aberrations but outcomes of the state’s own policies of urban development.

But these corrosive arts of governance operate differently, varying according to context. In those parts of our cities where, for example, land zoned for agricultural purposes has been converted to luxurious “farmhouses”, the bulldozers seem to lose their way. These areas eventually transform from being “unauthorised” to “unauthorised regularised” and finally to that most coveted of all the Kafkaesque urban categories of existence, “authorised”. And then, there are even newer processes of city making – the so-called greenfield developments – where former farmlands now play host to bewildering dramas of land politics. At these sites, complex financial and administrative arrangements are collaboratively utilised by both private and government agents to produce a variety of illegal acts upon the land. Village lands acquired by the state, and meticulously recorded in apparently incorruptible digital maps as intended for public infrastructure, are frequently taken over by well-off citizens and private developers who build private property across them. Satellites watch helplessly, etching digital information onto maps which have no real meaning. The land sequestered by private companies and individuals, more often than not, eventually converts to legal estate.

Poor migrants to the city also occupy spaces in ad hoc ways – actions similar to those of the urban rich – clinging desperately to any hope of finding shelter. This requires complex strategies of dealing with the state, land mafias, corrupt bureaucracies and the original landowners who sell their lands for “illegal” occupation. This, in turn, produces an urban environment of perilous negotiations and fragility. The occupants of the railway land at Haldwani have taken part in activities that are no more illegal than those at more up-scale localities. And, they have not circumvented the state’s laws to any greater degree. The difference lies in how those in power deal with the rich and the poor and their understanding of demolitions of poor localities as effective urban planning.

A criticism of bulldozer urbanism is not just a matter of bleeding-heart liberalism, it is also about asking if there is at all any public good in this approach to re-fashioning cities. Contemporary acts of dealing with so-called encroachments – through demolitions and evictions that mainly affect the poor – both irreparably damage already vulnerable lives while also failing as public policy. There is no public good in this at any level, for bulldozer urbanism proceeds from the principle of differentiated citizenship. What is worse, it offers no long-lasting solution to the problems of making better cities in any way. It diminishes the quantum of public welfare by uprooting populations from sites of educational, financial and residential security (already of uncertain value) without any meaningful positive outcomes. Bulldozer urbanism cannot offer any solutions to the real-world problems – housing, public infrastructure – of deeply unequal cities.

What is needed are holistic policies of urban planning that are not fractured because multiple authorities – railways, electricity and water boards, etc. – are allowed free play over what they might do with their lands when, after several decades, they “discover” their properties. This requires thinking of the city as an organism with complex social needs, rather than merely an economic entity. Imaginations of a “good city” can only come about through thinking of it as a social entity, before everything else. Cities require public utilities, but their individual actions cannot be allowed to determine the life of cities, for these do not address the needs of cities. This requires courage and foresight on the part of those in charge of the urban landscape.

Two other things are needed for producing liveable cities for all. First, it is important that the courts recognise their role as protectors of citizens from the arbitrariness of state action – the ways in which it treats different sections of the population. And second, as cities offer an escape and hope for the most marginalised from the oppression that rural life presents, it is important to develop a sense of compassion for urban life at its margins.

The writer teaches at SOAS University of London and is Honorary Professor at Shiv Nadar University, Delhi NCR