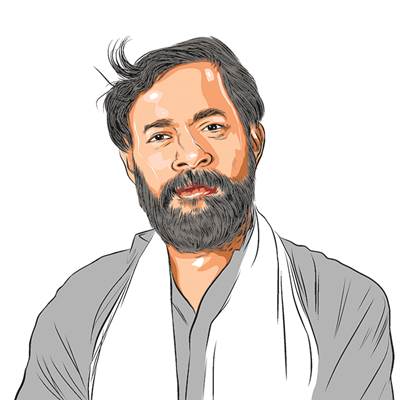

Opinion Yogendra Yadav writes: Let’s audit Bihar SIR. It makes for sad reading

Although SC interventions allayed fears of mass disenfranchisement, the exercise has left much to be desired from the standpoint of accuracy equity, transparency, fairness

Supreme Court interventions have allayed fears of mass disenfranchisement in Bihar SIR.

Supreme Court interventions have allayed fears of mass disenfranchisement in Bihar SIR. Now that the final electoral rolls for Bihar are out, as is the election schedule, here is a provisional audit of the SIR exercise. We assess the quality of the new voters’ list in Bihar on three globally accepted parameters of voter registration — completeness, equity and accuracy.

The first measure of the quality of electoral rolls is completeness, measured by the proportion of the eligible population that figures on the voters’ list. After the publication of Draft Electoral Rolls in Bihar, we had recorded on these pages (‘The missing voters’, IE, July 31) how the SIR resulted in a shocking drop in the proportion of adults who figured on the voters’ list, from 97 per cent to 88 per cent. The final voters’ list is somewhat of an improvement — 90 per cent of adults have made it to the list. However, the big picture has not changed. As Graphic 1 shows, the SIR has caused the sharpest drop in the electoral-population ratio. In September 2025, Bihar should have had 8.22 crore voters — the state’s adult population estimated by the Government of India’s Technical Group on Population Projections. The actual figure of 7.42 crore on the final electoral rolls indicates as many as 80 lakh potential voters missing from the list. Hardly a cause for celebration.

There is a mistaken sense of relief about the final figures, largely because the exclusions from the final list are less than the 65 lakh excluded from the draft rolls, and much smaller than the apprehension of deletion of up to 2 crore voters. If that level of mass disenfranchisement did not happen, the reason is not the SIR or the ECI, but the Supreme Court of India. Thanks to the constant monitoring by the Court, the ECI was forced into “damage control” mode, bypassing its own order and procedures. First, the non-submission of enumeration forms by a vast number was whitewashed by the filling of at least 20 per cent of the forms by BLOs, a forgery reportedly encouraged by the ECI. Second, as reported in this paper, the non-availability of the required documents with nearly two-fifths of the potential electors was made up by offering most of them a bypass through the dubious means of vanshavali — tracing current voters to someone in their family who featured on the electoral rolls in 2003. Finally, the SC’s belated order on Aadhaar served to check the disenfranchising impulse of the SIR.

The second parameter, “equity”, offers evidence of worsening. Equity is about representing all social groups in proportion to their share of the eligible population. While we await a deeper analysis of the impact of the SIR on various marginalised groups like Dalits and circular migrants, we do have evidence that the SIR has adversely affected the representation of women and Muslims. The accompanying graphic shows that the proportion of women in Bihar’s voters’ list has always been lower than their share in the population. Over the years, this gap had narrowed from 21 lakh in 2012 to just 7 lakh in January this year. The SIR has reversed this historical trend, reduced the share of women, and increased the number of missing women voters to 16 lakh.

The evidence is less clear for Muslims, since they are not an official category in the ECI’s record. But the use of name recognition software brings out an alarming fact: Muslims were 24.7 per cent of the 65 lakh voters excluded from the draft electoral rolls and 33 per cent of the 3.66 lakh names deleted from the final list, against their population share of 16.9 per cent in the Census. This translates to nearly 6 lakh “excess exclusion” of Muslims.

On the third parameter, “accuracy”, the SIR may have worsened the voters’ list. While we need a full audit that compares the accuracy score of the pre-SIR and the post-SIR lists, a preliminary analysis of some of the most common errors does not support the ECI’s claim of “purification” of the electoral rolls. The final voters’ list of Bihar has more than 24,000 gibberish names, about 5.2 lakh duplicate names, over 6,000 invalid gender entries (outside M, F, and T), over 51,000 invalid relations (other than mother, father, husband etc.), and over 2 lakh blank or invalid house numbers (discounting house number “0”). This is hardly a model of purification. In substantive terms, there are now more than 24 lakh households in Bihar with 10 or more electors (prima facie suspect, as defined by the ECI itself), housing 3.2 crore electors in total. In most of these, the final electoral rolls are worse than the draft rolls.

And what about the oft-repeated claim by BJP leaders, endorsed by the CEC, of cleansing the rolls of foreigners, allegedly Bangladeshis and Rohingyas? Curiously, the ECI’s daily bulletin on the SIR gave data on various reasons for exclusion, but never for the number of foreigners detected during house-to-house verification. The BJP did not file a single objection to any elector on this ground. The website of the CEO of Bihar displays 2.4 lakh readable records of objections to draft rolls. Of these, only 1,087 cases (0.015 per cent of the total electorate) were about someone not being an Indian citizen. Even these cases were mostly dubious (779 of these were self-objections, someone complaining against himself for being a foreigner!) or presumably Nepali (since only 226 names were that of Muslims). In any case, the ECI has accepted only 390 of these objections (of which only 87 are Muslims) and deleted their names. No wonder the CEC is not keen to share the data on foreigners whose names were deleted.

To these three substantive measures of quality of voter registration, we could add two process-related parameters — transparency and fairness. On these two counts, we don’t need to wait for a full future audit of the SIR. Sadly, the entire exercise has been anything but transparent or fair. Beginning with the refusal to publish or even respond to an RTI application seeking a copy of the Intensive Revision order of 2003 to refusing to release the final rolls data in the standard template, the ECI has gone against its norms, precedents, and its own manual, which mandated disclosures. The Supreme Court had to order it to publish the names of the 65 lakh persons excluded from the draft rolls. As a rule, the ECI withheld every piece of information that it was not legally mandated or ordered to disclose, just the opposite of what a poll body should do or the ECI used to do. The lack of prior consultation, the haste in implementation, the secrecy surrounding all decisions, and the combative mode of the CEC vis-à-vis the Opposition leaders — all contributed to an impression that the ECI was not a neutral umpire.

This provisional audit makes for sad reading, especially for an institution that has been a model for election bodies across the Global South and enjoyed a very high level of trust within the country. Any attempt to replicate the SIR outside Bihar, without learning lessons from this experiment, could open the floodgates for mass disenfranchisement. At the very least, it could erode popular trust in elections and hasten the backsliding of India’s electoral democracy.

Shastri and Yadav work with the national team of Bharat Jodo Abhiyaan. Yadav has filed a petition in the Supreme Court challenging the SIR. Statistical analysis was carried out by Bharat Jodo Abhiyaan’s data team