Opinion INS Vikrant sets sail: Why it is key to India’s maritime strategy

Abhijit Singh writes: Despite rising costs and vulnerability, the aircraft carrier continues to be at the heart of India’s maritime strategy

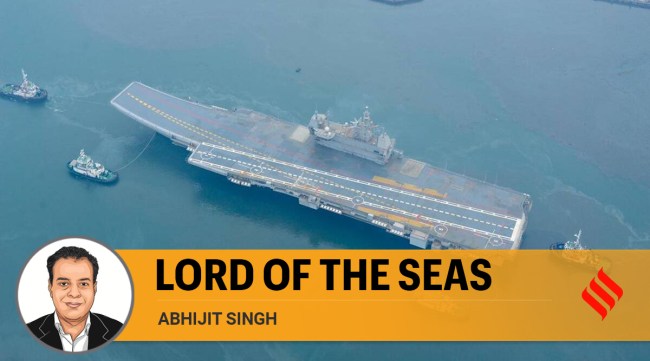

Abhijit Singh writes: Vikrant’s induction has stoked an old debate among strategic experts and observers about the relevance of aircraft carriers in the contemporary world.(Source: PIB)

Abhijit Singh writes: Vikrant’s induction has stoked an old debate among strategic experts and observers about the relevance of aircraft carriers in the contemporary world.(Source: PIB) The commissioning of the INS Vikrant is a landmark achievement for India. Developed by the Navy’s warship design bureau and constructed by the Cochin Shipyard Limited (CSL), the Vikrant is India’s largest and most complex indigenously built warship. With a displacement of 43,000 tonnes, the ship boasts an endurance of about 7,500 nautical miles and a cruising speed of 18 knots (significant for its size and tonnage). The ship’s integral fleet of MiG 29K aircraft, Kamov 31 early warning and MH-60R multi-role helicopters, as also state-of-the-art shipboard offence and defence systems, surveillance and fire-control radars, make it a formidable warfighting platform.

Vikrant’s induction, however, has stoked an old debate among strategic experts and observers about the relevance of aircraft carriers in the contemporary world. After the Navy’s top brass reiterated the need for a third aircraft carrier to protect Indian interests in the Indian Ocean, some commentators criticised the move, calling for a mindset change in the Navy. Sceptics say there is little point in spending billions for a carrier strike force to protect the Bay of Bengal or the Arabian Sea, when near-seas defence can be easily ensured from airbases on India’s island territories. Aircraft carriers, the doubters posit, are logistically unviable, and highly vulnerable to new hypersonic weapons and disruptive technologies. The flattop, they argue, is defenceless against modern-day underwater attacks, long-range strategic airpower and ballistic missiles; a virtual sitting duck in a conflict scenario.

The sceptics make a point. Aircraft operating warships are prized targets in wartime; not just on account of their enormous cost and susceptibility to enemy attack, but also for their symbolic value. For navies locked in combat, the destruction of the opponent’s aircraft carrier is a priority mission. Such ships are likely to be targeted in salvos of cruise and ballistic missiles — the kind of heavy ordnance that no floating platform can hope to survive, least of all an ungainly mammoth with its vital parts exposed to attack.

🚨 Limited Time Offer | Express Premium with ad-lite for just Rs 2/ day 👉🏽 Click here to subscribe 🚨

Yet, there is a compelling rationale for retaining the aircraft carrier. In peace and in war, no platform provides access to littoral spaces as thoroughly and emphatically as the aircraft carrier. Whilst ensuring effective sea command, it allows for a continuous and visible maritime presence that influences the cost-benefit calculus of the enemy commanders. Whatever its disadvantages, the aircraft carrier has the critical ability to alter the psychological balance in the littorals, which is why modern-day navies regard the ship as an indispensable asset.

The aircraft carrier ought, also, to be located in a conceptual framework. Ocean-going navies today need three types of conventional assets. The first category comprises “hard-power” assets — fighting platforms like destroyers, frigates, missile boats and attack submarines meant for combat operations in a naval battle. These are used in both offensive and defensive operations, and are meant to influence the tempo and outcome of a maritime conflict. The second lot is of “soft-power” assets like hospital ships, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief platforms, survey vessels, etc. These provide a valuable service and are crucial for a navy’s soft-power outreach and peacetime diplomacy. Finally, and most significantly, a navy needs assets for “power projection” — a crucial component of peacetime maritime strategy, and an embodiment of a nation’s strategic capability and political intent. A navy’s ability to project military power far beyond the home country is a metric of national influence and regional relevance.

This is not to suggest that the flattop no longer has a wartime role. It does indeed. But the ship need not necessarily be involved in high-intensity combat operations against adversaries. It must be seen as a fungible asset, in terms of its utility in advancing national objectives. As proponents point out, there is something about an aircraft carrier sailing through foreign waters that cannot be replicated by a submarine or a destroyer. The carrier could be replaced by lesser platforms that might do the job, but none can match its demonstrative impact.

And yet, India’s aircraft carriers have never quite been used as versatile assets, switching between power projection, soft power diplomacy and presence operations. That’s because the navy has rarely had the opportunity of operating two operational carriers. With the Vikrant joining the fleet — and the possible addition of a third aircraft carrier over the next decade — the Indian Navy could for the first time play a crucial role in shaping the power balance in the Indian Ocean.

Even so, India’s maritime planners confront a dilemma. The strategic objective of expanding influence in the Indian Ocean competes with the mission set of raising fighting efficiency and interdiction potential in the littorals. The Indian Navy must plan not only to project power and influence abroad, but also deter adversaries and mark its presence in the near-seas. The predicament naval planners face is that if particular aspects of naval operations are found lacking, should the larger maritime strategy (focused on aircraft carrier operations) be discarded in favour of an ad-hoc plan built around assets with doubtful efficacy. The consensus among experts is that Indian strategic capacity in the Indian Ocean region would be robbed of its vitality if the aircraft carrier is replaced with shore-based air power. Regardless of the latter’s perceived tactical advantages, it has never been particularly effective at sea.

The Indian Navy is also mindful of the ambition of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and the role that China’s aircraft carriers — the Liaoning, the Shandong and the recently launched Fujian (Type 003) — are likely to play in the Pacific and the Indian Oceans. Beijing is also said to be considering using aircraft carriers both for power projection and soft-power diplomacy — a key component of the PLAN’s “far-seas” strategy. Disquieting as Beijing’s maritime ambitions are for Indian watchers, Chinese plans to build six flattops by 2049 validate the need for aircraft carriers in maritime strategy and national security.

For Indian naval commanders, then, the questions surrounding the third aircraft carrier are entirely unnecessary. As they see it, an aircraft carrier is more than an instrument of utilitarian value. It is the beating heart that provides all naval effort with its essential vigour. As the famed Soviet admiral, Sergei Gorshkov, noted in his thought-provoking treatise, The Sea Power of the State, ideas on the deployment of maritime power need to be anchored in the logic of geopolitics and long-term state interests, and not on contingent assessments of imminent needs.

The writer, a retired naval commander, is head of the Maritime Policy Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi