Custody cases need human touch, rules SC

Hearing a child custody case recently, the Supreme Court held that these cases could not be decided 8220;solely8221; by interpreting legal provisions.

Hearing a child custody case recently, the Supreme Court held that these cases could not be decided 8220;solely8221; by interpreting legal provisions. It even laid out that while dealing with such cases a court 8220;is neither bound by statutes nor by strict rules of evidence or procedure nor by precedents8221;.

8220;It is a humane problem and is required to be solved with human touch,8221; observed a Bench headed by Justice C K Thakker.

The Bench, which also comprised Justice D K Jain, noted that in selecting a guardian, the court exercises parens patriae and is expected, and indeed bound to give due weight to a child8217;s comfort, contentment, health, education, intellectual development and favourable surroundings.

The Bench even asked courts to consider 8220;moral and ethical values8221; which, it felt, 8220;cannot be ignored8221; while deciding as to who should get the custody rights. According to the apex court, 8220;they are equally, even more important, essential and indispensable considerations8221;.

The court made these observations while dealing with a petition filed by Nil Ratan Kundu and his wife, who opposed the granting of custody of their six-year-old grandson to be their son-in-law. They urged the court to take into account the 8220;preference8221; of the child as well. 8220;Normally, in custody cases, wishes of the minor child should be ascertained by the court before deciding as to whom custody should be given,8221; the court said while declining the father8217;s plea that he was the natural guardian.

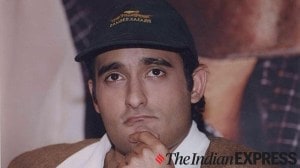

Setting aside the trial court8217;s decision, upheld by the High Court of West Bengal, the Bench agreed that character of the proposed guardian was one of the issues required to be considered by a court of law. In the present case, the father, Abhijit Kundu, is facing a criminal trial for the murder of his wife, Mithi Kundu, over dowry demands.

Finding infirmities in the earlier decisions, the SC allowed the grandparents to be the guardians of the child.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05