Bringing a child home: The journey of foster parents in India

As a new set of guidelines attempts to promote foster parenting in India, Abhinaya Harigovind maps the journey of foster parents — from having to shave off a beard to unrelenting questions: "why doesn’t your child look like you?"

Officials in the Women and Child Development (WCD) Ministry explained that foster care is distinct from adoption in that it is a temporary arrangement with the child staying with the foster parents for a period that may last for a few months to several years. (Express illustration by Komal)

Officials in the Women and Child Development (WCD) Ministry explained that foster care is distinct from adoption in that it is a temporary arrangement with the child staying with the foster parents for a period that may last for a few months to several years. (Express illustration by Komal)Nearly a decade ago, when a Rajasthan-based chef and his wife began fostering a toddler, they learnt to make a few changes — one of which involved his beard.

“We brought her home when she was 18 months old. The staff at the child care institution from where we got her were all women. So she was initially scared of me and would try to hide when I was around. We then realised that maybe it was my beard that was troubling her since she had never seen men at the institution. I shaved it off, and left it that way for four-five months. You cannot imagine the effect it had… slowly, we began to bond,” says the 40-year-old.

The need to “bond” and give a child “the happy childhood I missed” were what led him to want to adopt a child — and when that took inordinately long, go in for fostering.

“My sisters and I grew up without our mother. So when I was in Class 7 or 8, I remember thinking I would adopt a child at some point and give her everything she might need,” he says.

In 2014, he and his wife applied for adoption. “A year had passed but we didn’t hear back from the adoption agency. In the meantime, we got a text message that said fostering a child was also an option. I had not heard about fostering until then. I collected the details and applied. We got a call later saying we could meet children at an institution before we decide,” he says, adding that he and his wife were insistent that they wanted a foster daughter.

“We knew little about the child’s background, except that her mother was mentally challenged and was in an institution,” he says.

The Indian Express has withheld names of the foster parents and their foster children to protect their identities.

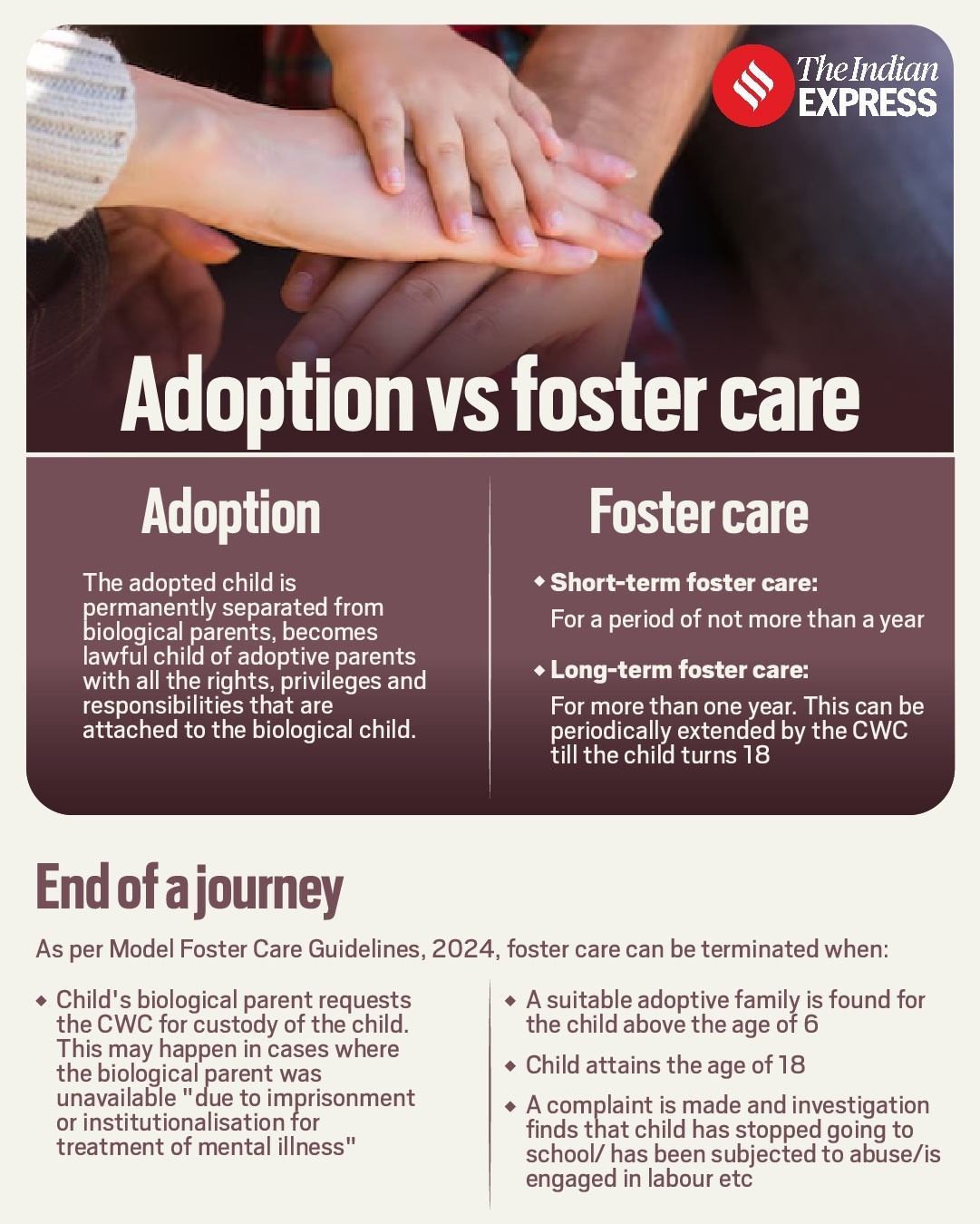

Adoption vs fostering

A less-tried and little-known child care option in India, fostering is aimed at providing the safety of a home and family to children in the 6-18 age group who may need temporary care away from their biological parents. These could be for reasons ranging from financial hardships to death, separation of parents or any of the reasons that make it difficult for the parent to rear the child.

Officials in the Women and Child Development (WCD) Ministry explained that foster care is distinct from adoption in that it is a temporary arrangement with the child staying with the foster parents for a period that may last for a few months to several years.

Once the child turns 18, foster care is “deemed to have concluded” and she has the option to either continue staying with the family or avail of an aftercare programme, which may involve vocational training or higher education.

While both adoption and fostering are governed by the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, the difference lies primarily in the fact that with fostering being a makeshift parenting arrangement, the child’s legal relationship with her biological family stays intact as opposed to adoption, where the child, once adopted, is entitled to the rights and privileges of a biological child, including inheritance rights.

Officials and experts say that it’s primarily because of the temporary nature of the arrangement — besides the lack of awareness, among other reasons — that fostering in India has never evoked the response that adoption has, with its long wait lists of prospective parents.

According to the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA), the nodal agency under the WCD Ministry for adoption, 34,988 prospective parents have registered for adoption though there are only 2,159 children who are declared ‘legally free for adoption’ by Child Welfare Committees (CWC), including 1,450 children with special needs.

But there are many more children who are in institutional care across the country who may not be legally free for adoption or whose chances of adoption are poor – they may be older than six and hence not preferred by prospective adoptive parents or may have special needs, among other reasons.

The CARA data shows that of 16,928 children in the 7-18 age group in child care institutions across the country, 3,312 fall under the ‘no visitation’ category — that is, their parents haven’t visited them in over a year — while 6,465 children fall under the ‘unfit parents’ category (those whose parents or guardians may be unable or unwilling to parent). The other children may be orphaned, abandoned, or surrendered.

It’s this pool of children who can potentially be put up for fostering. CARA data says that as of January this year, 1,610 children are in foster care in the country.

A senior CARA official said, “The best institutional care cannot replace the warmth of a family. But foster care has never really picked up in India. There isn’t much clarity or knowledge about it here, unlike in the West. Then there is the dilemma of the child leaving at some point since foster care is meant to be temporary.”

Shilpa Mehta, founder at Foster Care Society, an NGO that works with the Rajasthan government in implementing the foster care programme in the state, says, “In India, parenthood is about having ‘ownership’ of the child, parents want to be able to do things like give the child their surname. This is a major challenge.”

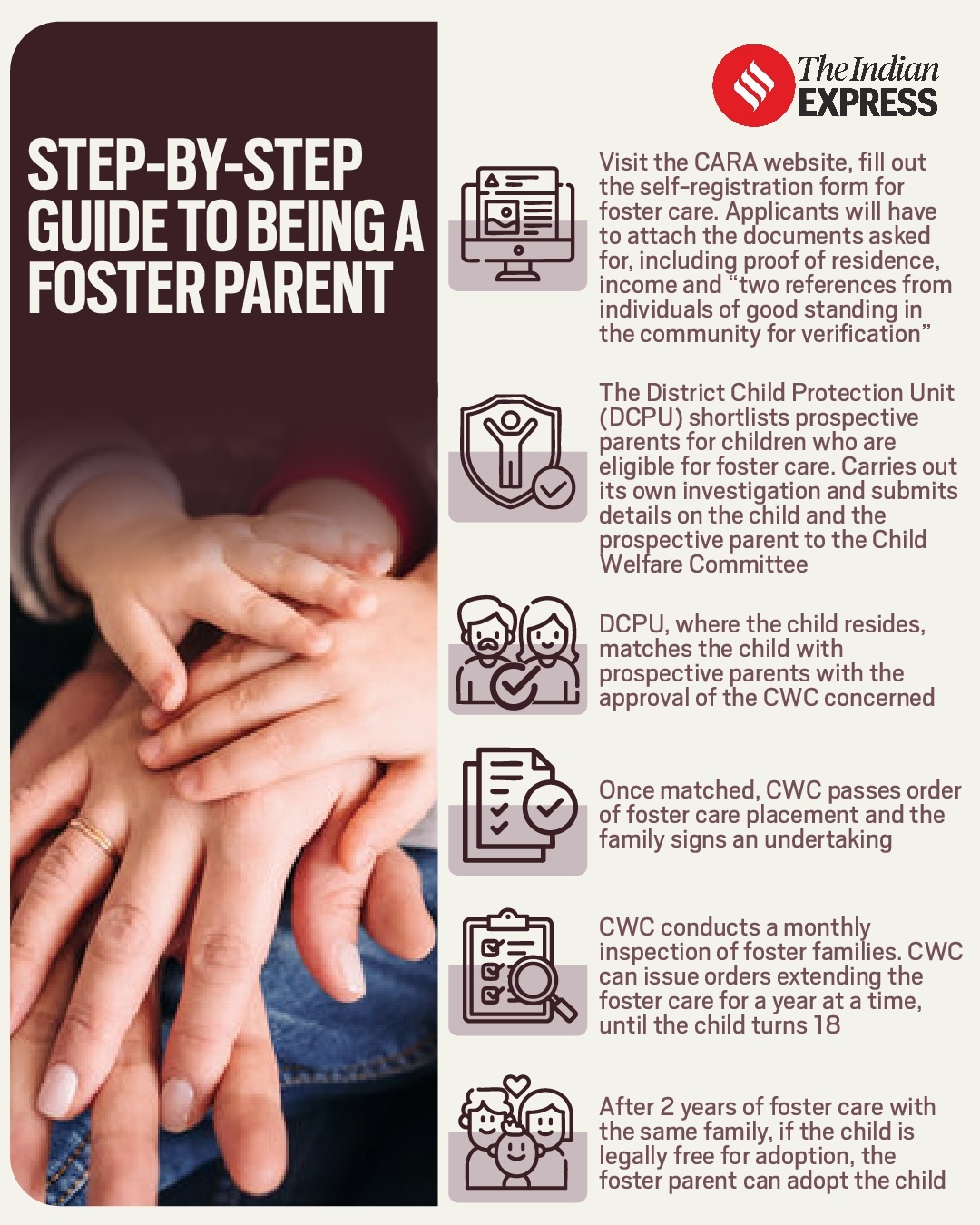

WCD officials said the recently revised Model Foster Care Guidelines, 2024, is an attempt to facilitate fostering and streamline the existing process.

For one, the process is now centralised, where prospective foster parents can register online through CARA — until now, they had to approach District Child Protection Units (DCPU) in individual states to apply. The new guidelines also allow anyone aged 35–60 years to foster a child, regardless of their marital status — earlier, only married couples could foster a child.

Adoption vs foster care

Adoption vs foster care

The new rules also make it easier to transition into adoption — a child in foster care, provided she is legally free for adoption, can be adopted by the family after two years instead of the earlier five years.

Since January this year, when CARA opened its online portal for registration for foster care, 209 prospective foster parents have applied. According to the WCD Ministry, the caregiver family, if eligible, is entitled to a monthly grant of Rs 4,000 per child.

Shy child to being the ‘boss’

The 40-year-old chef in Rajasthan says his fostering journey was full of new discoveries. Though he tackled his beard early on, more challenges were to follow.

“She was in a child care institution where they served non-vegetarian food. But where we were staying on rent, the condition was that we couldn’t cook non-veg at home. When the child came home, she wouldn’t eat. We would feed her with great difficulty. Once, we secretly smuggled in some eggs and boiled them. She saw the eggs and squealed in delight…anda, anda. We then started taking her out for non-vegetarian food,” he says.

The couple also had to move house. “When she started going to the playground, there were rumours…people would say, ‘where is this child from; we don’t know her, don’t play with her’. When we got to know of this, we moved out to a new place,” he says.

Despite the early hiccups, he says they watched the child go from being a “reserved child” to somebody who is now the “boss” among her group of friends. “She was so reserved that I would ask her to be a little more mischievous. But now she has opened up…she skates, she paints.”

Yet, there are times when he is reminded of his foster parent status. For instance, he says, he can’t take his daughter along when he travels abroad. “We have not been able to get a passport made for her…because her parents’ name is not on the document. Also, fostering doesn’t allow us to give our surname to the child.”

How to become a foster parent

How to become a foster parent

Satyajeet Mazumdar, Director-Advocacy at Catalysts for Social Action, a non-profit organisation that works in the child protection space in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Goa and Karnataka, says that while the new guidelines are a step forward, much needs to be done.

“The new guidelines don’t make any mention of preparation and orientation of the prospective foster family — what they can expect, what issues they might face, and how to address these. Also, a system to address issues of documentation has not been put in place…getting a passport (for the foster child) has been an issue. Since the objective of foster care is temporary care, the guidelines also don’t say anything about what the system is doing to strengthen the biological family… particularly in cases where the biological family is dealing with financial difficulties,” he says.

Elsewhere in Rajasthan is a 56-year-old who is a single parent to two girls – an 18-year-old she adopted in 2006 as a six-day-old and a 13-year-old foster daughter.

A retired airport manager, she says that when she met her foster daughter at an institution in 2017, the child was eight. “She was at an age where she was already aware of everything, so she took time to adjust. She had been in an institution and had not seen family bonding. Also, since her early education was inadequate, I put her in a school where she had to learn from scratch,” says the 56-year-old, adding that she always wanted to be a mother.

“I don’t have a big family…only two sisters. I wanted somebody to call me ma,” she says of her decision to adopt and foster.

Though foster care was an option only for married couples until the recently revised guidelines came about, what helped people like the 56-year-old to become a foster parent was a concession in the earlier guidelines that said states could adopt or adapt the guidelines.

She says that after adopting her first child, she chose to foster the second time around since she was by then in her late 40s and realised she may not “have the time to wait the few years it might take to adopt a child”. According to CARA’s eligibility criteria, the maximum age a single prospective adoptive parent can be is 55 years for a child between the ages of 8 and 18 (110 years for a couple).

For an elderly couple in Maharashtra, the first foster parents in their district, the decision to go in for fostering was prompted by a tragedy — the death of their 26-year-old son, who was then working in the US.

“Our son died from cardiac arrest five years ago. We were in shock; he was our only son. A friend suggested that we bring a child home. By that time, we had crossed the age for adoptive parents,” says the foster father, 61, who retired from a multinational corporation.

“When we applied for foster care, the CWC had a lot of questions. They asked me how we would take care of the child since I wasn’t working. We had to convince them that we were getting rental income and had other investments. In 2022, we met three boys at an institution. We told them they were going to stay with us, and we have only two conditions — they should study, and do something good with their life,” he says.

Of their 12-year-old foster son, he says, “He told us his mother was no more and that his father used to drink all the time and beat them. He was in an institution and nobody from the family had gone to meet him there. It will take time for him to adjust… He was studying in a Marathi-medium school earlier but is now able to go to an English-medium one. Our hope is that he will be able to complete his graduation,” he says.

While the couple has applied to foster another child, an official in the district said that they were no longer eligible considering the age limit.

“Age should not be a factor…if somebody is mentally, physically, financially fit, they should be able to foster. They could be a little more liberal with the age limit,” says the foster father.

An official with one of the District Child Protection Units in Maharashtra said the district now has one other foster family, apart from the 61-year-old and his wife.

On the process they follow before placing a child in foster care, the official says, “An enquiry into the family is done before they are matched with a child. Also, before the child goes to the home, the counsellor and superintendent at the institution prepares her. Once the child has gone to a foster home, we verify and monitor how the child is doing. The CWC can issue orders extending the foster care for a year at a time until the child turns 18.”

The 40-year-old chef says the temporary nature of fostering has never deterred him. “I know people who have been on the adoption waitlist for eight years or longer, but have not been able to adopt a child yet. I know foster care is not a permanent setup, but if the child lives with us for a month, two years, 10 years…the child has a family,” he says.

The retired airport manager in Rajasthan agrees. “Strangers would often ask me, the younger child (her foster daughter) does not resemble me, does she resemble her father? I usually say yes without giving any explanation. But sometimes, I would tell them about my fostering journey, in the hope that they might tell somebody else and others would be inspired to take it up.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05