Who moved the Dead Politician? The journey of an artwork

With 66 artists from over 25 countries set to display their works at the Kochi Biennale later this week, The Indian Express traces the journeys that artworks make — across thousands of kilometres, in the cargo hold of a plane or inside a crate in a temperature-controlled vehicle, sometimes with armed personnel in tow, before finally reaching the exhibition floor

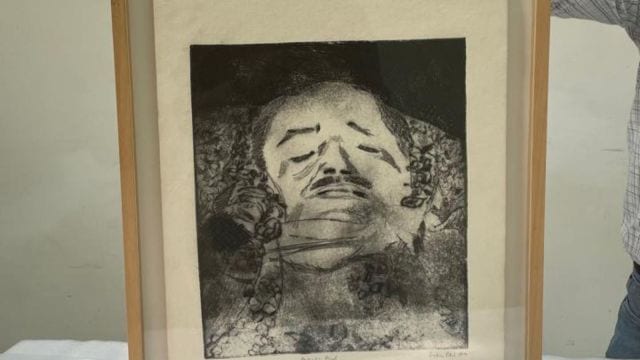

The Dead Politician is still in transit. Somewhere between departure and display. (Express photo)

The Dead Politician is still in transit. Somewhere between departure and display. (Express photo)The dead Politician lies face down. On white butter paper, on a table that’s lined with a foam sheet. First, the edges of the sheet are taped. Then comes the plastic covering. In less than four minutes, the Dead Politician is packed away.

The 1971 etching is one of two works by the late poet and artist Gieve Patel that Delhi’s Vadehra Art Gallery is sending to the upcoming edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, which starts on December 12. The other is Patel’s Monument, created the same year.

Dead Politician and Monument are now on their way to Kochi, covering the 2,000-km journey in the cargo hold of an airplane, inside a wooden crate with foam cavities.

Behind every such high-value artwork that eventually finds its way to a gallery or museum, where it is bathed in soft lights and admired in silence, are similar unseen journeys — of crates, handlers, climate controls and countless careful hands.

Shifting an artwork

Two years ago, Star Worldwide, one of the biggest players in the fine art logistics industry in India, had to move five 3rd-century CE artefacts from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) museum in Nagarjunakonda, Andhra Pradesh, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for an exhibition titled ‘Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 BCE–400 CE’.

In 2023, five 3rd-century CE artefacts had to be moved from the ASI museum in Nagarjunakonda, Andhra Pradesh, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for an exhibition (Photo: Star Worldwide Group)

In 2023, five 3rd-century CE artefacts had to be moved from the ASI museum in Nagarjunakonda, Andhra Pradesh, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for an exhibition (Photo: Star Worldwide Group)

There were the usual issues. And then, some more. Each of the artefacts weighed nearly two tonnes, and were made of centuries-old limestone that is porous and susceptible to damage. The real challenge: moving them out of the island.

“Taking the works out of the museum was difficult because of their weight. Multiple forklifts and cranes had to be used. The biggest issue was getting them to the mainland, which required the artefacts to be placed on a ferry that runs only from 10 am to 3pm,” says Roshan Lal, Senior Manager, Projects and Exhibition, Fine Arts, Star Worldwide, who supervised the transit.

Following the nearly one-hour journey on water, the artefacts were transported by road to Hyderabad airport, from where they were taken to New Delhi and further to New York in a cargo freighter aircraft.

Preparation for the transportation of an artwork begins months in advance. The paperwork takes even longer. After an artwork has been identified, a survey or a condition check is carried out.

“This includes recording the exact height and weight of the artwork, its state and location,” says Rajesh Gulati, founder of MasterArt Logistics, an art logistics firm.

Based on the condition check, shippers identify the equipment needed at different stages of transit, from fork or scissor lifts to machine skates, dollies and even cranes.

Each of the artefacts weighed nearly two tonnes, and were made of centuries-old limestone that is porous and susceptible to damage (Photo: Star Worldwide Group)

Each of the artefacts weighed nearly two tonnes, and were made of centuries-old limestone that is porous and susceptible to damage (Photo: Star Worldwide Group)

While the nitty-gritties are being worked out, shippers check if their clients — the gallery or the artist who wants the artwork moved — have specific requirements.

Leading Indian galleries, including Mumbai’s Chemould Prescott Road, Delhi’s Vadehra and Kolkata’s Experimenter told The Indian Express that they work with multiple shippers, across India and internationally.

“We give our clients a quotation that depends on the destination, handling capability, insurance compliance, etc,” says Jagruti Suryavanshi, logistics head at Chemould Prescott Road.

Step two, and perhaps the most crucial of the process, is packaging the work.

Over the years, as art moved beyond traditional oil-on-canvas or watercolour works to embrace newer mediums and more ambitious ideas, including the sprawling installation art of the late 20th century, the logistical demands kept mounting.

Star Worldwide, a fine art logistics firm, was roped in to move the artefacts. But this was no ordinary shipment. Multiple forklifts and cranes had to be used (Photo: Star Worldwide Group)

Star Worldwide, a fine art logistics firm, was roped in to move the artefacts. But this was no ordinary shipment. Multiple forklifts and cranes had to be used (Photo: Star Worldwide Group)

Think Shilpa Gupta’s For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit (2017-2018), a work that uses 100 speakers, microphones, printed text and metal stands. The work has travelled around the globe, from Kochi to the Venice Biennale, from Brisbane to Edinburgh and Baku (Azerbaijan). Or Saad Qureshi’s Night that Witnessed II (2017), a mixed media work that uses wood ash, black sand, charcoal and Indian ink on Gabon plywood. The exposed paint and charcoal layer demanded that the tautness of the canvas remained intact. The work, which travelled from London to Delhi last year, had to be packed in a travel crate with anti-vibration material to ensure that the surface doesn’t come in contact with the packaging. There’s also Vibha Galhotra’s Melting, which has a metal globe perched on a thin stand. What makes the transit of Melting challenging is the thick layer of melted (and then solidified) wax that falls from the top of the sphere all the way down.

“We have to keep training and upskilling ourselves as new mediums come in. There is never a one-rule-fits-all solution for fine art,” says Atul Mithal, founder of Star Worldwide Group, among the oldest fine art logistics companies in the country.

Mithal founded Star Worldwide in 1996 primarily as a mover and packer of international household goods, though his clients, including ambassadors, often had priceless artworks to be moved.

Things took a turn in 1997, when the British High Commission asked for 300 works to be shipped from London’s British Museum to Delhi and Mumbai for an exhibition to mark 50 years of India’s Independence.

Star Worldwide’s reputation landed it the role of transporting a priceless artwork in April this year — 16th-century Renaissance artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s 420-year-old Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy.

The stakes were high: It was the first time an original Caravaggio was travelling to India. The baroque painting, currently valued at $50 million, had to be taken to different locations in the country — the Italian Embassy and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) in Delhi and the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bengaluru.

As part of tarmac supervision, Lal of Star Worldwide, and his team boarded the freighter to oversee the artwork’s offloading from the plane “in the right way”.

“First, we checked the bay where the aircraft was parked. In case of any dangerous goods in that area, we would have stopped the painting’s offloading,” he says.

The crate was brought out, after which a pallet truck took it to a bonded warehouse. After clearance from the Customs, the team loaded the crate using a forklift into the company’s temperature-controlled vehicle, after which it set out for its destination: the Italian Embassy. Multiple escorts accompanied the Caravaggio — one each from the Italian Embassy and Star Worldwide, along with CISF personnel. “The escorts were to ensure the vehicle wasn’t stopped on the way. This is followed for all high-value shipments,” says Lal.

At the Embassy, the Caravaggio was uncrated and a condition check done by two conservators (often appointed by the exhibition organiser). The painting was then packed again and kept in a temperature-control room there. The airport security stayed with it till the day of display, after which another set of personnel took over.

The fear of loss, damage

Obviously, not every artwork is a masterpiece valued at $50 million and in need of armed personnel, but the possibility of a painstakingly done piece getting damaged or lost in transit remains an artist’s worst fear.

Painter and sculptor Jayasri Burman is still living that nightmare. In the early 1990s, Burman, then an emerging Kolkata-based artist, had an exhibition of 22 works at a Mumbai gallery. While none of her works sold at the exhibition, they didn’t come back to her either— not for the next 10 years.

“When they didn’t arrive in a few days, I checked with the gallery and was given all the shipment documentation. For years, I kept enquiring with the airport authorities and the police,” says the 65-year-old artist.

She recalls how, several years later, one conversation led to another and eventually the story reached her son’s friend, whose brother worked at the Kolkata airport. “The only proof I had of the exhibition was the invite. The young man did due diligence. I was finally told that the works, all 22 of them, were in a flooded warehouse at the airport.”

When finally retrieved by Burman, the works, all oil on canvas, were damaged. In fact, she continues to restore them. One of them, Untitled, 1992, was even showcased at Art Mumbai last year by Chawla Art Gallery.

The loss of her works was “heartbreaking”, says Burman, but it was the helplessness that still cuts deep. “I didn’t even know who I could blame. Every person involved in the process seemed to have done their job, at least on paper,” she says, adding, “Today, things have become a lot better.”

Much of this change can be attributed to the evolution of the logistics industry — art is no longer just cargo. While most art handlers in the business are goods loaders, companies train them extensively before they are allowed to handle art. At Star Worldwide, for instance, art handlers are often transfers from the ‘relocation’ department (that handles household goods). “We monitor people’s performance. If we think someone has the dexterity and manual skills to handle art, we move them,” says Mithal.

Anil Vishwakarma, who started as an art handler at Universal Art 13 years ago and is now a supervisor, recalls packing a three-part terracotta sculpture by Delhi-based artist Manjunath Kamath. “Each piece was given a one-inch foam base and packed in crates. Then, it was wrapped in butter paper to protect the edges, followed by plastic. After that, a 6-mm foam was put around it. That was covered in bubble wrap. All of this was packed in with shrink film (which wraps tightly). That helped us understand where to hold the sculpture while putting it in the crate and while taking it out,” Vishwakarma recalls.

While moving art requires flexibility of approach, certain guidelines are sacrosanct. For instance, art handlers cannot wear rings, watches or belts since any of these could be a potential source of damage — a minor graze, a jerk or fall can be costly. Wearing gloves is mandatory at all times.

Shippers are often also responsible for the de-installation after an exhibition and for making a record of the “impact” on a work of art — what it endures during the duration of its display. “Mosquitoes, cobwebs, dust,” explains Lal, adding that conservators are brought in, if required.

An unexpected challenge

Transporting art also requires mounds of paperwork, with a substantial part of it devoted to insurance since art, even when not a marquee masterpiece, is treated as a high-premium, high-risk asset.

Suryavanshi, logistics head, Chemould Prescott Road, says, “For gallery-to-buyer consignments, the gallery typically covers insurance until delivery confirmation. For museum loans or art fairs, insurance is arranged wall-to-wall — from a work’s removal at origin to destination installation.”

Rattan snake during the installation at NMACC in Mumbai (Photo: MasterArt Logistics)

Rattan snake during the installation at NMACC in Mumbai (Photo: MasterArt Logistics)

Customs is a different ball game, with countries having different import rules. “If clients are unsure about their legal and Customs duties, we don’t ship the artwork because we can’t have the work in a Customs warehouse without the right temperature control and attracting damage or penalty for staying there,” says Prateek Raja, co-founder of Experimenter.

While the evolution of technology has helped the business immensely, as Mithal says, “nothing can replace the human element” since there’s almost always an unexpected challenge.

Like it happened during the installation of Rattan Snake, a nearly 30-foot-long sculpture, at the recent Bvlgari ‘Serpenti Infinito’ exhibition at Mumbai’s Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre (NMACC). One of the major attractions at the exhibition, the sculpture was meant to be wrapped around one of the pillars at the venue.

Rattan snake after the installation at NMACC in Mumbai (Photo: The Refinery)

Rattan snake after the installation at NMACC in Mumbai (Photo: The Refinery)

To hook the six-part installation, the pillar had to be covered with a beam. MasterArt staff, however, arrived at the venue to a beam a size bigger. This meant the sculpture wouldn’t wrap around the pillar the way it was intended, like a snake.

“We had half a day before the exhibition opened. We had to come up with innovative ways to give it its original length around the beam because the artist had left. We used a scissor lift and scaffolding, and stretched and pressed the work and installed it successfully, just in time,” Gulati recalls.

The sculpture ended up being among the major attractions at the exhibition. Yet, like countless artworks that travel across cities and continents, its behind-the-scenes story remains largely unspoken.

As for Dead Politician, it is still in transit. Somewhere between departure and display.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05