Circulatory Lives Project- Konkan Coast by Ishan Tankha

Circulatory Lives Project- Konkan Coast by Ishan Tankha

In the inner room of the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum’s Special Project Space, is what looks like a makeshift train compartment, with two wooden benches facing each other. A screen placed on the wall between them is playing on loop a video featuring Anil Jadhav, a Mumbai native who has moved back to his ancestral village of Ukshi in Ratnagiri. In the video, Jadhav muses on the connection he feels with Ukshi. “My grandparents came from Ratnagiri,” he tells us, before explaining that he himself was born and brought up in Mumbai. As he shows us around his village and his house there, he wonders aloud about his roots. Where do I belong, he asks, adding, “Going to my village feels like going home, but returning to Mumbai is no less about returning home.”

This video forms the core of the ongoing exhibition “Mumbai Return”, the result of three years worth of research done by urbz, an experimental urban collective and research institute, and the Mobile Lives Forum, a Paris-based think tank that is fostering research and debate on the future of mobility worldwide. The exhibition begins by proposing an alternative way of understanding rural to urban migration in India, and proceeds to discuss the larger idea that people might be rooted in more than one place. “We assume that in this very mobile world, people would be uprooted. But what we have found is that people are more likely to have more than one root, and this is particularly strong in India,” says Matias Echanove, urbanologist and co-founder of urbz.

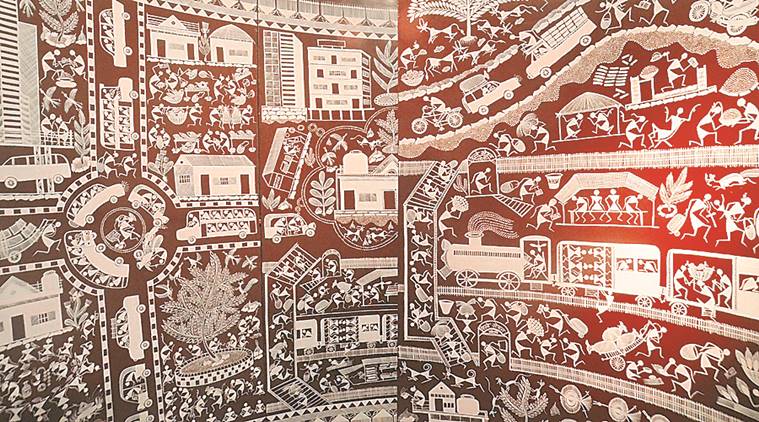

The exhibition focuses on the migration patterns that have developed between Mumbai and the Konkan region over many generations. The team, led by Echanove and fellow urbanologist and urbz co-founder Rahul Srivastava, worked with four Mumbai families, who have their ancestral villages in the Ratnagiri district, to establish the “circulatory journey” that marks their movements. The circulatory lives thus lived are best evoked in the installation created by Warli artist Sanjay Bhoir. Two large surfaces covered in artwork that represent — separately — the rural and the urban life, curve towards each other at the centre, where the merging of elements from the city and the village are represented.

This installation is part of the first section of the exhibition that documents life in Konkani villages, using Instagram photos, short videos shot by the “migrants” themselves and the layout plans of houses that have been built by them. The next section of the exhibition talks about the journey between the village and the city — how it has changed over time thanks, firstly, to the railways, and secondly, to mobile technology that has all but eliminated the temporal distance between the two locations. The final two sections explore how migrants, once they move to the city, build communities and dwellings that create and transform neighbourhoods. Echanove says, “Many neighbourhoods that come up like this are classified as ‘slum areas’, but they are much more than that. They have, over time, become real places, with a sense of identity and aesthetics.”

As people moved to the big city, they continued to maintain a link with their villages in various ways — sending back money, buying land, setting up businesses and building homes. “We found that these relationships are characterised by a projection towards the future and towards reinvestment,” says Echanove, “It isn’t just about spending the holidays in the village, or building a holiday home there. They will open small shops or invest in agriculture. Often, the economic and industrial development in these villages is triggered not by government policy, but by the people. And there are all kinds of patterns here. It’s not just the old who live in the village; we see young people, born in Mumbai, going back to the village because they see a role for themselves there or an opportunity. ” It is part of a distinct pattern of urbanism that is seen across India, and in this pattern, the difference between the city and village represents not an unbridgeable gulf, but the distance that exists between two points on a continuum. Therefore, it is not useful to merely think of the village as representing the “rural” and the city representing the “urban”. “Both the village and the city form a part of the ‘urban realm’,” says Echanove.

The exhibition is on at Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum, Mumbai, till July 31

Circulatory Lives Project- Konkan Coast by Ishan Tankha

Circulatory Lives Project- Konkan Coast by Ishan Tankha