The truth about things

What did a pioneer of modern Japanese fiction have to do with Rashomon?

Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s best works are incredible short stories.

Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s best works are incredible short stories.

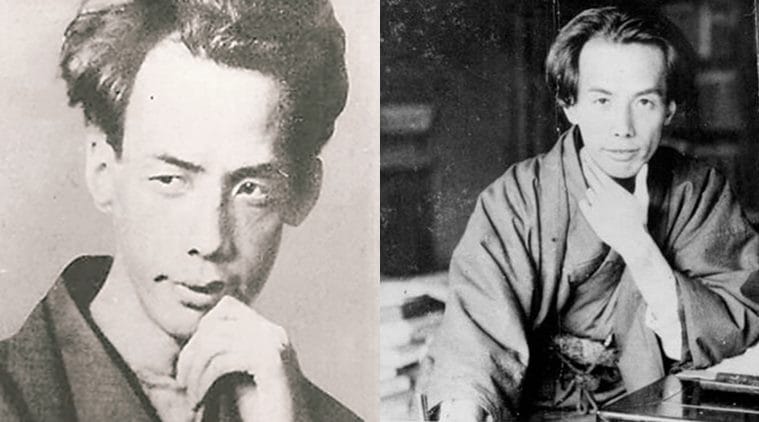

There is a man behind the classic film Rashomon, behind even the director Akira Kurosawa. He is a writer whose work is unaccountably unknown in India, though the keenest Kurosawa fans lurk in our midst. Our collective ignorance of Akutagawa Ryunosuke is inexplicable, since he is regarded as one of the pioneers of modern Japanese fiction and the country’s premier award for new writing is named after him. Besides, his best works are incredibly short stories. Short enough to be finished on a very short Metro ride. He should be popular in these hurried times.

Rashomon the film draws its title and setting from one of Ryunosuke’s shortest stories, a tiny masterpiece set in the late Heian period, when warlords asserted themselves against the decadent imperial court of Kyoto. The city which Basho would recall in the haunting “bird of time” haiku is going to seed. Its Rashomon gate has become the refuge of vermin and scoundrels; its upper storey teems with the unclaimed corpses of a dying city, and the vagrants who make a living by robbing the dead.

Rashomon the story appeared in 1915 in a faculty journal of Tokyo Imperial University, from where Ryunosuke graduated in English literature. It made absolutely no waves, not even a ripple, not even in Japan. If readers were told that they were seeing the armature of one of the greatest films of the 20th century, they would have laughed out loud. Because Rashomon the story has only two characters — a freshly discharged retainer contemplating death by starvation, and a crone pillaging the dead to stave off that fate — apart from numerous corpses in various states of disrepair. The dramatis personae of Rashomon the film, and their famously conflicting accounts, are not from this story.

The highwayman, the samurai and his wife and the witnesses to what passed between them, the characters who are known the world over thanks to Kurosawa’s film, were drawn from the story In a Bamboo Grove (‘Yabu no Naka’). One of Ryunosuke’s later works, it appeared in a magazine in 1922, five years before he committed suicide with a drug overdose.

One print edition of these stories is available in India from Penguin Classics: Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories, translated by Jay Rubin with an introduction by Haruki Murakami. Incidentally, Rubin has been the force propelling Murakami to the English readership and has done much to generate interest in contemporary Japanese literature. But the fact that his collection, like others, puts Rashomon on the cover like a marketing hook — in his lifetime, Ryunosuke was celebrated for other short stories like Nose — suggests that his author has become of special interest everywhere, not only in India. The algorithm on Amazon’s US site computes that Ryunosuke’s stories are bought along with collections by one of America’s finest short story stylists: Ernest Hemingway. Maybe people are reading him, after all.

Before internet bookstores, it was really hard to find a copy of the Penguin Classics collection in India. But other translations have been loose on the net for years, especially at academic sites. Search for Rashomon and Other Stories for an edition in which the first translation of In a Bamboo Grove appeared.

Rashomon is cinematically superb. The use of wavering, ambiguous light and minimal sets (the result of budgetary constraints) suggested new ways of showing and telling which went beyond cinema to influence the stage. But the central device of conflicting accounts of witnesses, which is now called the Rashomon phenomenon, gave it cult status. And that was entirely Ryunosuke’s contribution. His story begins abruptly with the ‘Testimony of a Woodcutter under Questioning by the Magistrate’, and runs rapidly through six other depositions, including that of a dead man’s spirit, who speaks through a medium. It is not only a story, but a fractured mirror held up to the human race, exposing a trait which questions its ability to bear witness. The unreliability of witnessing compromises the law, ethics and historical narrative, pillars of human civilisation and philosophy.

Issues involved in forgetting and remembering are being closely studied now, thanks to the growing prevalence of dementias and other degenerative disorders which erase memory and even personality. Kurosawa’s film drew attention to the phenomenon of false memory, which was investigated by Freud, among others — the ease with which we fill in the blanks of memories that are either lost or were never actually experienced, borrowing from environmental cues, culture, media, interlocutors and even the memories of other witnesses. The Rashomon phenomenon suggests that the authorised version of reality is merely the one which we have agreed to support. This is reality by consensus, a matter of belief. To ask if it is really, actually, absolutely real is to miss the point.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05