Between Worlds

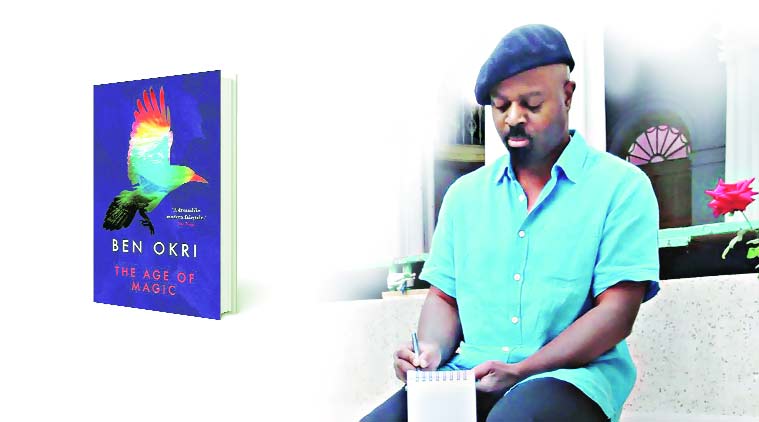

Nigerian poet and author Ben Okri, who was in India recently, on his new book, his belief in brevity and why we are much more than our colonial past.

Like most writers, Ben Okri likes his cup of tea. In our half-an-hour interview, he has two potfuls of Earl Grey. He doesn’t drink his tea in measured sips, but in eager gulps. Like Azaro, the spirit-child narrator of his 1991 Booker-winning novel The Famished Road, Okri seems to have a voracious appetite for life. He was in Kolkata recently for the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival. The first thing he noticed after landing was the much-maligned Big Ben replica that a Trinamool MP erected in the middle of an arterial road in the city in his effort to “make Kolkata, the London of the East”. Surprisingly, Okri doesn’t scoff at the miniature Big Ben, nor is he patronising; he calls it “cultural re-appropriation”. Okri talks about his new book The Age of Magic, and explains why we are much more than our colonial past. Excerpts from an interview:

Like most writers, Ben Okri likes his cup of tea. In our half-an-hour interview, he has two potfuls of Earl Grey. He doesn’t drink his tea in measured sips, but in eager gulps. Like Azaro, the spirit-child narrator of his 1991 Booker-winning novel The Famished Road, Okri seems to have a voracious appetite for life. He was in Kolkata recently for the Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival. The first thing he noticed after landing was the much-maligned Big Ben replica that a Trinamool MP erected in the middle of an arterial road in the city in his effort to “make Kolkata, the London of the East”. Surprisingly, Okri doesn’t scoff at the miniature Big Ben, nor is he patronising; he calls it “cultural re-appropriation”. Okri talks about his new book The Age of Magic, and explains why we are much more than our colonial past. Excerpts from an interview:

You feel that there is nothing wrong in the blatant recreation of London in Kolkata through structures like the Big Ben? Is it not symptomatic of our need to ape the West?

Often, I have come across such situations where people of colour get offended when white people dress like them or talk like them. Many of my Nigerian friends find it offensive when white women dress up in African robes. They feel it’s racist. Well, I am wearing a white man’s attire too (pointing at his linen shirt and trousers). Am I apologetic about it? When you build a Big Ben in the middle of Kolkata, it’s cultural re-appropriation. It’s like saying that despite your colonial history and the painful associations it has, you can look at a Big Ben and say, ‘Hey, I like this and I want this in my city’.

As a Nigerian author, do you feel that we are burned by our colonial past? Did you have to undo the Western influences you grew up with?

The other day, I was talking a walk around the city. I reached a particular street, where there was a little, nondescript Kali shrine at the porch of a building. It was easy to miss, but I kept seeing people almost walking past the shrine and then coming back to pay obeisance. It was god space. How do you think a Jane Austen would describe such a scene? Everything will be a dry appropriation. No Western author has the vocabulary to do justice to a scene like this. Western education doesn’t equip you with that. Which is why, I had to unlearn much of my Western education before writing The Famished Road. I needed a new idiom.

There was a time in your life when you were an activist/journalist in Nigeria. Today, Nigeria is plagued with Boko Haram. Can you tell us what ails Nigeria?

First you tell me what ails India? It’s the same story everywhere. In the 1970s, I was living in a ghetto in Nigeria. I wrote about the corruption and the mismanagement. My editors weren’t interested. So I decided that I will talk about the reality of my country through stories. Today, Boko Haram is a major concern in Nigeria. But getting rid of it won’t make everything right in my country. We need to do something about the inequitable distribution of wealth. Northeastern Nigeria, which is the hotbed of Boko Haram, faces abyssal poverty. There is corruption everywhere. Unless we do something very drastic about killing corruption in counties like yours and mine, things won’t change. Politicians should be very afraid when they even think about misappropriation of funds.

Tell us about stoku — the fusion of short story and haiku — in your storytelling.

I am a big believer in brevity. I was always fascinated with the way nature expresses so much with such brevity. A huge tree is condensed to a seed. I always search for the smallest unit of storytelling. I read about haiku and then I devised stoku. It takes me a long time to compose them, sometimes years. I distil my experiences to tell a stoku. But I also have to ensure that it is not too dense.

Tell us about your latest book, The Age of Magic.

I have only one sentence to describe my situation. I wanted to write a book about happiness and this is it.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05