After All This Time

If acting was a rite of passage for Karan Kapoor, photography was his calling. In his first exhibition in India, Kapoor’s photographs from a 30-year old series on Anglo-Indians in Bombay and Calcutta, and one on Goa, find themselves in the spotlight.

Karan Kapoor first began taking photographs when he was 15 years old.

Karan Kapoor first began taking photographs when he was 15 years old.

Indians over a certain age will recognise Karan Kapoor instantly. His good looks, with the cleft chin inherited from his father Shashi Kapoor, had ensnared many a heart when he appeared as the “dream lover” in Bombay Dyeing ads in the 1980s. This was soon after he finished his studies in England and returned to Mumbai in 1984, when his mother, actor Jennifer Kendall, died. “The modelling just happened. It was fun, and a good way to earn money,” he says. Acting, on the other hand, didn’t just “happen”. For someone from the illustrious Kapoor family, movies were a rite of passage. As a boy, he had made small appearances in Shyam Benegal’s Junoon, as well as 36 Chowringhee Lane, but it was Sultanat in 1986, that marked his debut in Bollywood. This, and subsequent films like Loha and Afsar, didn’t exactly set the box office on fire and Kapoor eventually withdrew from the Hindi film industry to pursue his first love — photography.

Kapoor, 54, had started taking photos at the age of 15, armed with a second-hand Nikon gifted by his parents. Among the earliest photos he took were during the family’s frequent holidays in Santo Vado, Goa, where they owned a house. “It was called ‘The Love House’”, he says, over the phone from London, “We would go there for every holiday and we knew everyone who lived in the village.” Goa in the 1980s was still idyllic, a state of sunshine and susegad. But as tourism grew, Kapoor felt the need to document the changes he saw in the state. The pristine Baga Beach, for instance, as it appears in a few photos taken in 1982-83, is empty but for the resident fisherfolk and would be unrecognisable to most visitors today.

The exhibition will have photographs from a series on Anglo-Indians that Kapoor did in 1979-80 in Calcutta and Bombay.

The exhibition will have photographs from a series on Anglo-Indians that Kapoor did in 1979-80 in Calcutta and Bombay.

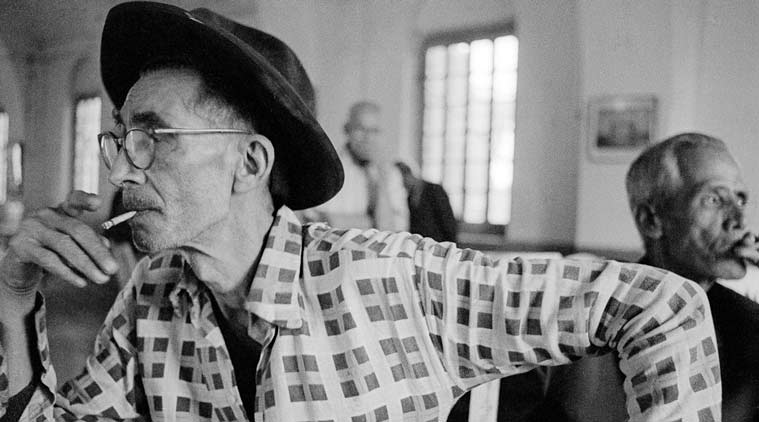

Many of these photographs will be displayed at a travelling exhibition next month, organised by Tasveer, called ‘Time and Tide’, Kapoor’s first in India. The silver gelatin prints of the 45 black-and-white photographs will be displayed first in Mumbai, then in Delhi, Jaipur, Kolkata and Bangalore. Also part of the exhibition are photographs from a series on Anglo-Indians that Kapoor did in 1979-80 in Calcutta and Bombay. He grew interested in the subject, partly thanks to his own life, as a child of an Anglo-Indian marriage. But it was Aparna Sen’s 36 Chowringhee Lane, produced by his father and starring his mother as an Anglo-Indian teacher, that made him want to take a closer look. “Many Anglo-Indians who had lived through the last days of the Raj were old, and I felt it was important to meet them and record their memories of what life had been like for them under the British and how it had changed after India’s independence,” he says.

Kapoor’s first calling had been as a photojournalist when, at the age of 17, he began freelancing for publications such as The Indian Express, Debonair and the now-defunct Keynote magazine, besides working on films like Utsav and the Merchant-Ivory production, The Bostonians, as a still photographer. His assignments took him all over India — from the courtesans and dancing girls of Mumbai’s Falkland Road, to the wrestlers of Varanasi and the Bhands of Kashmir. Kapoor eventually moved to London, where he freelanced for publications like The Sunday Times, Vogue and Marie Claire, before making a shift to advertising photography. London was highly competitive, he says, and advertising even more so. “My reportage experience helped, because clients appreciated the edge of realism that I could bring to my pictures.”

Kapoor no longer has the patience to take on a project like the Anglo-Indian series. “Film was very expensive, so you couldn’t waste a single frame. This meant spending time with the subject, getting to know them and finally, getting that one great picture,” he says. But patience has its rewards; in works, such as the one featuring a photograph of Daphne Sampson, winner of the 1956 Marilyn Monroe lookalike contest, Kapoor is able to successfully evoke an age long gone.

Kapoor is now keen to photograph Mumbai, a city that he still calls home and which, he says, continues to shock him with the pace at which it is changing. “The skyline astonishes me every time I see it,” he says. Although his annual visits to Mumbai only last a week, Kapoor makes time to shoot, particularly on his walks down Juhu Beach, located right behind Prithvi Theatre. With the exhibition opening next month, he hopes to stay back for a lot longer. “My kids are grown up, and now I would like to spend more time here. I’ve never had a major professional project in India, and that’s something I’m keen to explore now. Because of the exhibition, in a way, I feel like I’m coming back home.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05