Dhurandhar-inspired ‘spy’ memes flood the internet: Coping with humour?

The memes expose a shared fatigue with the done-to-death “enemy” plot and the persistent feeling of being instructed, time and again, to feel a certain way.

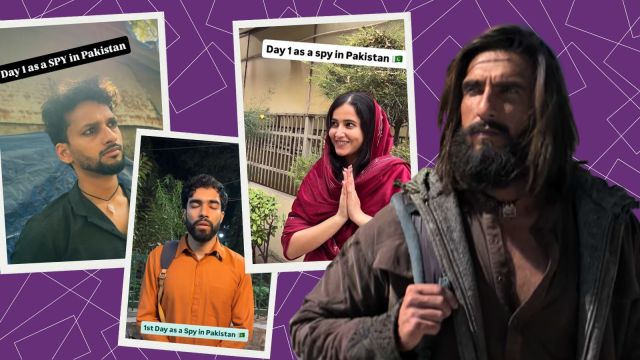

The Dhurandhar-inspired "spy" memes have found creators and consumers on both sides of the border. (Screenshot/Instagram/YouTube)

The Dhurandhar-inspired "spy" memes have found creators and consumers on both sides of the border. (Screenshot/Instagram/YouTube)Aditya Dhar’s Dhurandhar is the only topic of discussion wherever I go. Whether it’s gushing over Akshaye Khanna’s dance moves entering a Balochi camp or expressing concern over the violence shown in the film, everyone has something to say about it. The film has not only ignited necessary debate and criticism, but also become fodder for viral jokes. This blend of provocation and humour is most evident on social media platforms like Instagram, which are flooded with tongue-in-cheek memes about what an Indian spy would do in Pakistan. In response, Pakistanis created their own versions, depicting a day as a Pakistani spy in India.

The Dhurandhar-inspired spy memes parody the film’s espionage tropes and its chest-thumping nationalist message. They exaggerate disguises by using stereotypical depictions. The characters have kajal-lined eyes, wear a burqa or a skullcap, and litter Urdu terms like “janaab” and “bhaijaan” into the conversation to depict a Pakistani ‘spy’. On the other hand, a vermillion tika on the forehead, a dhoti, and a turban are used to represent an Indian.

The format is simple. Each reel plays the film’s version of the famous Sahir Ludhianvi qawwali “Na Toh Karwaan Ki Talaash Hai” as the characters walk around being inconspicuous, or at least trying to be. They begin with the “spy” being caught by a local, who asks them questions to confirm if they are indeed Indian or Pakistani, to which the character gives rehearsed answers. Their covers are blown within minutes.

View this post on Instagram

Both sides use specific cultural quirks that make the reels extremely funny to consume.

In one instance, the “spy” is told he will be introduced to “bade sahab,” to which his instinctive response is to get alcohol from Gurugram and buy “chakhna” (munchies) from Blinkit. Another shows a girl covering her head with a hijab who picks up a book thrown at her and touches it to her forehead, a particularly Hindu custom. Someone folds their hand in a ‘namaste’ while responding to an “as-Salaam-Alaikum” or reaches down to touch the greeter’s feet.

View this post on Instagram

Their Pakistani counterparts give themselves away by quoting Pakistan’s rare win over India in the T20 World Cup and waxing lyrical about Imran Khan’s “tabdeeli”.

View this post on Instagram

These memes use satire and irony to dismantle the provocative effects of a film that arguably expects its audience to react rather than reflect.

An amalgamation of extremes, Dhurandhar is unapologetic in its storytelling. It does not shy away from aggression, nationalism, and masculinity. Many have hailed it as a masterpiece that fuels nationalist fervour, while others say it escalates cross-border antagonism. It was met with mixed-reactions in Pakistan as well, with some lamenting the lost opportunity of telling a story that was, technically, theirs to tell.

Meanwhile, Dhurandhar’s technical brilliance and the performances make it stand out from films made on similar topics, such as Uri: The Surgical Strike, Fighter, The Kashmir Files, and Article 370.

These works spotlight the growing repository of hyper-nationalist films in Indian cinema. Anticipation is already building for Dhurandhar’s sequel that releases in March 2026. Before that, Border 2 is slated to release on January 23, 2026, just three days before Republic Day. The proximity of these releases may further reinforce recurring themes of nationalism and masculinity within mainstream cinema.

The “spy” memes lighten that seriousness. It may be too far-fetched to call a spontaneous internet trend a “unifying factor” between the two countries. Neither do they erase the hostility, nor do they promise any future peace. They, however, neutralise (rather unknowingly) the volatile discourse surrounding the India-Pakistan geopolitics. Audiences use humour and irony to stay away from narratives designed to aggressively provoke them into feeling anger, fear, and nationalistic pride. There are no rebuttals or protests against this. There’s only ridicule to tame the narrative.

Of course, not everyone’s guided by the need for subversion. Social media algorithms reward participation in trending formats regardless of political intent. For many creators, that may be the sole reason to jump onto the bandwagon.

But humour has long been the internet’s coping mechanism in tense situations. Many Indians posted memes in reaction to the mock drills conducted in parts of the country in May. Someone mocked their ‘corporate slavery’ lifestyle, working between air raid sirens. Another questioned if they should still study for their exams. The vitriol later did not lessen the urge to crack jokes. A post went viral where some Indians sent water bottles to Pakistani actress Hania Amir when the Indus Water Treaty was revoked, earning a few laughs.

Screenshot/Instagram

Screenshot/Instagram

Hilarity, in such times, comes instinctively to many. One does not have to defend Pakistan or take a moral stand. You just have to laugh at the absurdity of it all. The laughter also carries its own implications. Meme culture is quietly disruptive in a media ecosystem that thrives on negativity and outrage. They expose a shared fatigue with the done-to-death “enemy” plot and the persistent feeling of being instructed, time and again, to feel a certain way.

Then, there’s another grim reality. No matter how hilarious, these “spy” jokes may lose steam soon, but the India vs. Pakistan rhetoric is unlikely to fade away. The memes, however, betray a public response that resists being uniformly shaped by nationalist narratives. Rather than passive recipients, audiences in both countries appear capable of reading such messaging critically and deciding how, or whether, to engage with it.

That, in itself, is telling enough.

Akanksha is a freelance digital journalist.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05