Vanvas in the age of noise

The vanvas we crave today is not geographical — it is psychological.

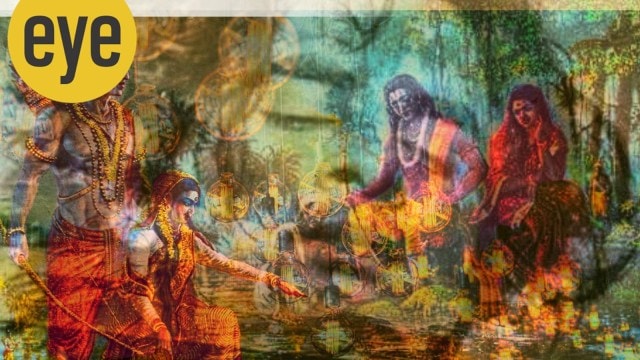

True vanvas is therefore not running into trees — it is running into truth. (Credit: Suvir Saran)

True vanvas is therefore not running into trees — it is running into truth. (Credit: Suvir Saran)It began, as awakenings so often do, with a picture on my phone. A blurred, burning sun — doubled, dissolving, dreamlike — hovering above a horizon that looked more like memory than morning. Beneath it glowed a single word:

Eremitism — the act of gradually fading from the lives of others, not out of malice but from a desire for solitude or renewal.

The image lingered in my mind like incense. Perhaps because birthdays arrive disguised as mirrors. Perhaps because November carries its own hush, a soft, smoky stillness that settles on the skin of thought. Or perhaps because India — saffron-soaked and stirred into a feverish fervour — is re-staging the Ramayana in public squares and televised temples, and I found myself wondering about vanvas, the Indian archetype of retreat.

Not the political vanvas now performed as pageantry.

Not the grand, gilded, government-approved vanvas.

But the private one — the ancient ache to walk away, for a while, from noise but not from life, from performance but not from purpose, from chaos but not from compassion.

What, after all, is vanvas?

Is it exile or is it exfoliation — the peeling away of illusions until only essence remains?

Is it escape or is it examination — the courage to confront what we carry and what we conceal?

Is it leaving the world or learning to see it without distortion?

Ram’s retreat into the forest has been reduced, over the centuries, to a costume drama. But the truth is far quieter, far more subversive: his vanvas was not abandonment, but apprenticeship. It was not escape from the kingdom but education for the kingdom. It was not flight from reality but a fiery refining by it.

And as I sat staring at that doubled sun on my screen, I realised something simple and startling:

The vanvas we crave today is not geographical — it is psychological.

Not walking away from the world, but walking toward the self.

Not disappearing, but discerning.

We live in an age where solitude must be defended like a dying species. Where stillness has become a luxury item. Where introspection has to fight for oxygen. Where retreat is romanticised but hardly understood. Where the forest we seek is not in Panchavati but in the cluttered chambers of our minds, which long — desperately, devoutly — for quiet.

And yet, even in this age of noise, the wisdom of the Gita arrives like a cool river across the forehead. It tells us, with its unwavering gentleness, that one does not escape action. One only escapes attachment. One cannot renounce the world; one can only renounce the feverish demand that the world behave as we wish.

Krishna’s counsel to Arjuna is uncompromising:

The forest is not outside you.

The battlefield is not outside you.

The kingdom is not outside you.

They all reside within.

If you flee one without facing the other, you have fled nothing.

True vanvas is therefore not running into trees — it is running into truth.

It is not external exile — it is inner equilibrium.

It is not subtraction from society — it is the purification of participation.

And the Upanishads echo this with an even deeper whisper. They remind us that the quietest cave is the chamber of consciousness, not the Himalayas. That the purest pilgrimage is not to distant shrines but to the still centre of the self. That there is a forest flowering inside us — fragrant, fathomless, forever — waiting to be walked with wonder.

Guru Nanak, that sage of the seamless, said it with a smile that could slice through centuries:

Why go to the forest to find the One

when the One is already pulsing through your veins?

Kabir sharpened it further:

Dekho ghat hi mein Hari ka niwaas hai re.

Look — the Divine lives in the vessel of your being.

What then is the point of vanvas?

Not departure — but discovery.

Not renunciation — but realisation.

Not removal from the world — but the removal of the walls within us that prevent us from seeing the world as sacred.

And then come the Sufis — those wanderers of wonder, those dancers of divine delirium — who remind us that solitude is not silence; it is tuning. Rumi whispers:

“Wherever you stand, be the soul of that place.”

Not “run away to a quieter place.”

Not “withdraw until the world behaves.”

But:

Become light, wherever life has placed you.

For the Sufi, vanvas is a swirling — a turning inward that turns the outer world translucent with truth. A retreat that does not reject society but refines one’s relationship with it. It is not a separation from humanity but a softening into it.

So why then, in this moment, in this month, in this mood, do I feel drawn toward retreat?

Because the world has become a carnival of compulsions.

Because public life now demands performance over presence.

Because religion is too often rehearsed and rarely realised.

Because politics is louder than prayer.

Because attention is the new altar at which we lose ourselves.

Because quiet has become a question mark.

And yet, the soul — stubborn, sacred, sincere — longs for a different kind of return.

Not to the forests of mythology,

not to the deserts of eremitism,

but to the inner river that refuses to run dry.

The vanvas I feel rising within me this birthday is not a desire to disappear.

It is the desire to deepen.

Not to vanish, but to vibrate differently.

Not to sever ties, but to slow the spinning.

Not to escape life, but to experience it without the excess.

A vanvas without vanishing.

A solitude without severing.

A silence without surrender.

A reminder that the forest is a frequency.

Ram returned from his vanvas not defeated, but distilled.

He came back not with bitterness but with balance.

Not with triumph but with tenderness.

Not with armor but with awareness.

And that is the return I want — not applause, not arrival arches, not some ceremonial celebration, but a homecoming into my own clarity. A way of being in the world that is less reactive, more reflective. Less demanding, more discerning. Less fractured, more full.

The sages were not wrong.

The mystics were not mistaken.

The poets were not merely performing.

They all knew what we keep forgetting:

You do not find peace by leaving the world.

You find peace by leaving behind the illusions that distort it.

And when you do, when you have walked through your inner forest and heard its quiet truths, the world suddenly softens. Streets seem less sharp. People less punishing. Days less demanding. Divinity less distant.

Because you have returned — not from exile, but from illusion.

Not from society, but from scarcity.

Not from life, but from forgetfulness.

And in that moment — clear, calm, complete —

you realise that i is not about where you go,

but who you become when you come back.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05