‘Street photography is like hunting; you need intuition, speed and a loaded gun’: Pablo Bartholomew

A walk-through with the photographer at an ongoing Delhi exhibition on street photography, and on why the split-second matters and the dance between revelation and secrecy

Photographer Pablo Bartholomew. (Credit: Pablo Bartholomew)

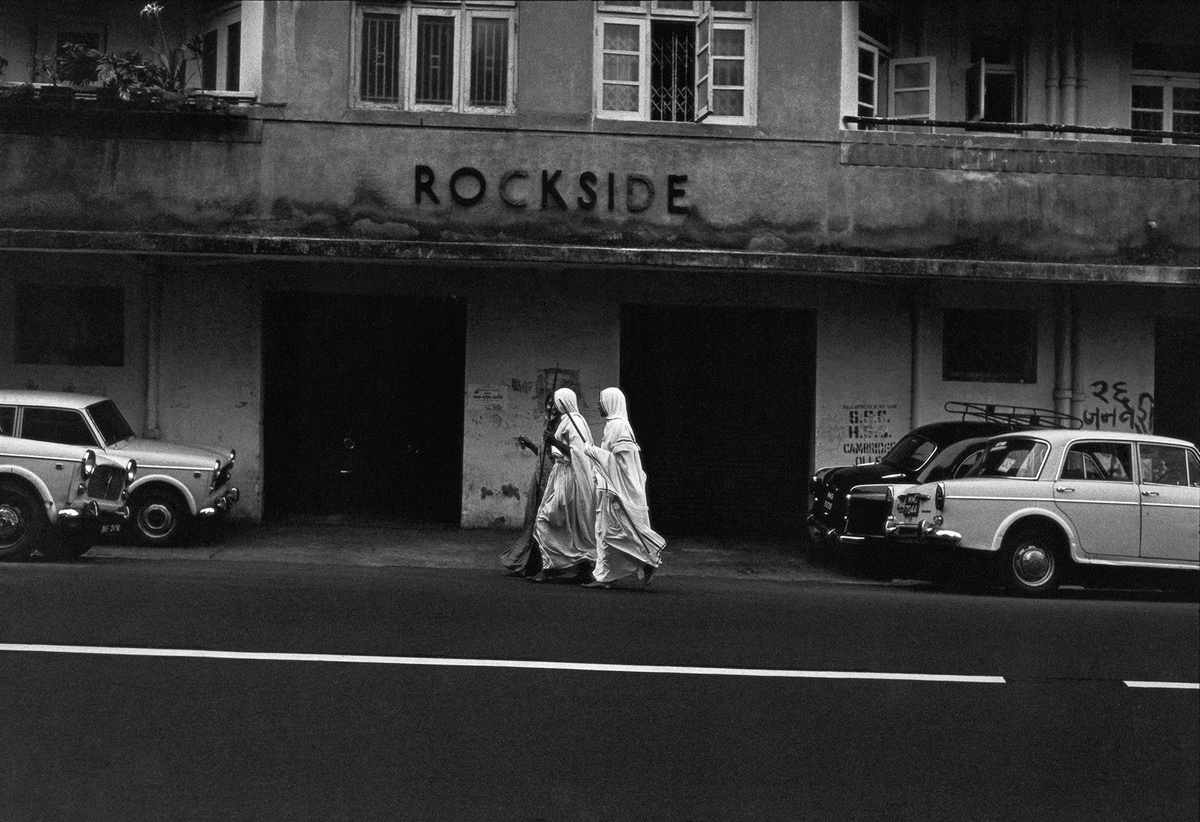

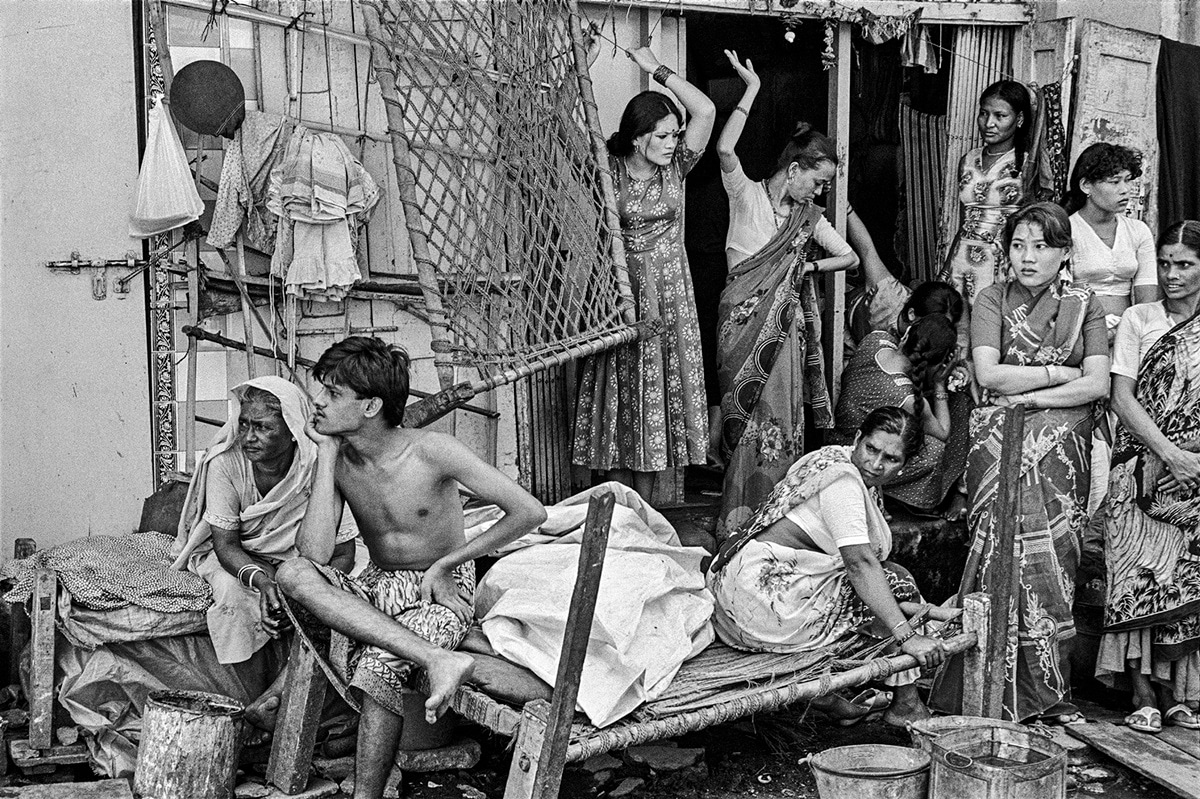

Photographer Pablo Bartholomew. (Credit: Pablo Bartholomew) IT’S IN the walking, in the unexpected, the unknown, in the-just-around-the-corner moment. Street photography has always been a craft that turned the ordinary into something magical. One such is Ketaki Sheth’s photograph ‘Jain Nuns’, Walkeshwar Road (Bombay, 1989). Against the dark backdrop of a building are two figures in white, their identity masked by their covered heads, walking away from the pull of parked cars. The photograph lets you interact with the surroundings as if you are actually there. Another such is Sooni Taraporevala’s photograph, ‘Women of Kamathipura’ (Bombay, 1987). This well-known shot presents the uncertainty of the moment as it compels one to engage with the streetscape and the people in the frame.

Ketaki Sheth’s ‘Jain nuns’, Walkeshwar Road, Bombay, 1989. ©Ketaki Sheth (Credit: Photograph courtesy Ketaki Sheth and PHOTOINK)

Ketaki Sheth’s ‘Jain nuns’, Walkeshwar Road, Bombay, 1989. ©Ketaki Sheth (Credit: Photograph courtesy Ketaki Sheth and PHOTOINK)

These are part of the exhibition at Delhi’s Photoink gallery where 23 black-and-white photographs from the archives of Sheth, Pablo Bartholomew, Raghu Rai and Taraporevala present the poetry of street photography. Curated by Devika Daulet-Singh, “The Passerby”, which closes on June 26, takes one back to simpler times. “A time,” reads the gallery note, “when permission and consent were not negotiated in writing and the photographer could photograph with tacit understanding from passers-by.”

Sooni Taraporevala’s ‘Women of Kamathipura’, Bombay, 1987. ©Sooni Taraporevala (Credit: Photograph courtesy Sooni Taraporevala and PHOTOINK)

Sooni Taraporevala’s ‘Women of Kamathipura’, Bombay, 1987. ©Sooni Taraporevala (Credit: Photograph courtesy Sooni Taraporevala and PHOTOINK)

From 1970 to 2000, called the golden period of photography, these images capture the everyday on city streets, from posing eunuchs to cart pushers, sleeping men to horses and cars. In this interview, Delhi-based Bartholomew, 66, talks about how street photography has changed, the performance and drama of it, and why it calls for a loaded gun.

Excerpts:

How is street photography today different from the Seventies and Eighties?

Nowadays, it’s just a button you press to get an image. Back then, it was a process of time. You take a photo, you have to finish the role and you process it. Sometimes, if you’re out in the field, you collect all the rolls and go back to the studio, look at it and edit it, which can, sometimes, take months. Back in 1989, when I was in the Northeast exploring the Naga tribes, it took me more than two months to take the pictures and come back to process it.

Buy Now | Our best subscription plan now has a special price

Nowadays, it’s something you can do with your eyes shut. Just one click and voila! You’d have an image without having any knowledge of the mechanism behind the picture.

Suppose you want a certain effect, you want to throw something out of focus or if you want to put everything in focus, how would you do it? You had to learn the technique. Nowadays, you don’t have to. That is the primary difference between photography of olden days and now.

With an analogue camera, how would you know you have seized the moment?

Look at Raghu’s photograph, ‘Two Men’ (Old Delhi, 1970). If he was even a millisecond late, the image would have been different. The old man’s walking stick in the background would have been blocked by the man in the foreground. And the picture won’t be as it is now. It illustrates that the split-second matters and it can change the portrayal of a photograph. It’s like hunting. You need intuition and speed, and a loaded gun, of course!

Raghu Rai’s ‘Two men’, Old Delhi, 1970. ©Raghu Rai (Credit: Photograph courtesy Raghu Rai and PHOTOINK)

Raghu Rai’s ‘Two men’, Old Delhi, 1970. ©Raghu Rai (Credit: Photograph courtesy Raghu Rai and PHOTOINK)

Do you see a difference in people’s attitude in front of the camera now?

The difference is that everybody knows what a mobile is now and how it clicks pictures. People are posing, smiling, making faces, throwing hand signs. In those days, people weren’t self-conscious or awkward, they were more natural and candid. They didn’t even notice, sometimes, thanks to our small portable handheld cameras.

So, you were like a spy on the street?

I wouldn’t say ‘a spy’, but ‘a fly on the wall’ is more like it. What were the challenges of street photography then? There were these myths about photography. When I was in China in 1987, they didn’t want to be photographed, there was this prevailing fear that the camera takes away your soul.

Tell us about your photograph ‘Eunuchs strike a pose’ (Grant Road, Bombay, 1976). How did you approach them?

Pablo Bartholomew’s ‘Eunuchs strike a pose’, Grant Road, Bombay, 1976. ©Pablo Bartholomew (Credit: Photograph courtesy Pablo Bartholomew and PHOTOINK)

Pablo Bartholomew’s ‘Eunuchs strike a pose’, Grant Road, Bombay, 1976. ©Pablo Bartholomew (Credit: Photograph courtesy Pablo Bartholomew and PHOTOINK)

There are various ways. One is to engage with the subject, the other is to observe. Eunuchs, anyway, have an interesting element. They make eye contact with you; they want money from you. So, there’s this whole drama and performance element in there.

Then, there are others like the ‘Parsi beggars’, Fort (Bombay, 1976). When I posted the photo online, people were shocked: ‘Oh, how can there be Parsi beggars?’. God knows what the story behind it is, but they were there on the street. When they saw me taking a picture, they hid their faces because in those days, the Parsi population was so small that if this got published, they would be recognised. It’s that whole hiding and secrecy that makes the image.

Soror Shaiza is an intern with The Indian Express

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05