© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

Jitish Kallat, Public Notice series (2003-10), on show at GOMA, Brisbane. (Credit: Courtesy the artist)

Jitish Kallat, Public Notice series (2003-10), on show at GOMA, Brisbane. (Credit: Courtesy the artist)Satish Gujral, Partition series, ’40s-50s

The catastrophe of the Partition is well-documented and Satish Gujral was a witness to the bloodshed and violence that accompanied it. Born in Jhelum in 1925, as a young child he accompanied his father in helping refugees relocate to India, and the trauma he experienced was to influence his art forever. “Partition is close to my heart and what I witnessed remained with me and was reflected in my work. Art was a medium to express that turmoil,” stated Gujral in an interview to The Indian Express in 2010. The painful memories led to several acclaimed works in the ’40s and ’50s, including Days of Glory (1952-86) with its huddled and helpless protagonists seated in isolation, and The Despair (1954), a dark depiction that portrayed loss through its wailing subjects.

Buy Now | Our best subscription plan now has a special price

MF Husain, Zameen, 1955

Considered one of his seminal works, in Zameen MF Husain encapsulated his love for the land. The panoramic painting that won him the National Award of the Lalit Kala Akademi award in 1955 explores the relationship between the people and the earth. Divided into various segments, the figures come together to tell the story of India, the daily life and the festivities. The motifs range from a rooster to a packhorse, bull and the wheel, several of which became recurring themes for the artist.

MF Husain’s Zameen, 1955. (Credit: Courtesy National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi)

MF Husain’s Zameen, 1955. (Credit: Courtesy National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi)

KG Subramanyan, The Tale of the Talking Face, 1970s

The artist-pedagogue started working on the series during the Emergency declared by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Comprising black-and-white drawings, the works that were also published as a book in 1989, depicted the perils of democracy and how authoritarianism can only bring suffering to the people. The allegorical satire had as its central protagonist an autocratic princess whose dictatorial measures brought hardships on her kingdom.

KG Subramanyan, The Tale of the Talking Face, 1970s. (Credit: Courtesy Art Heritage Gallery, New Delhi)

KG Subramanyan, The Tale of the Talking Face, 1970s. (Credit: Courtesy Art Heritage Gallery, New Delhi)

Gulammohammed Sheikh, City For Sale, 1981-84

The epic painting referenced how sectarian violence had become commonplace in Gujarat. The multilayered canvas encapsulated and merged disparate scenes from the city of Baroda, Sheikh’s home since 1955. His largest work till then, it had riots raging in one part of the city, even as everyday life continued for others, represented through scenes that had people watching a movie, Silsila (1981), and a woman with a vegetable cart headed into town.

Gulammohammed Sheikh’s City For Sale, 1981-84. (Credit: Courtesy the artist)

Gulammohammed Sheikh’s City For Sale, 1981-84. (Credit: Courtesy the artist)

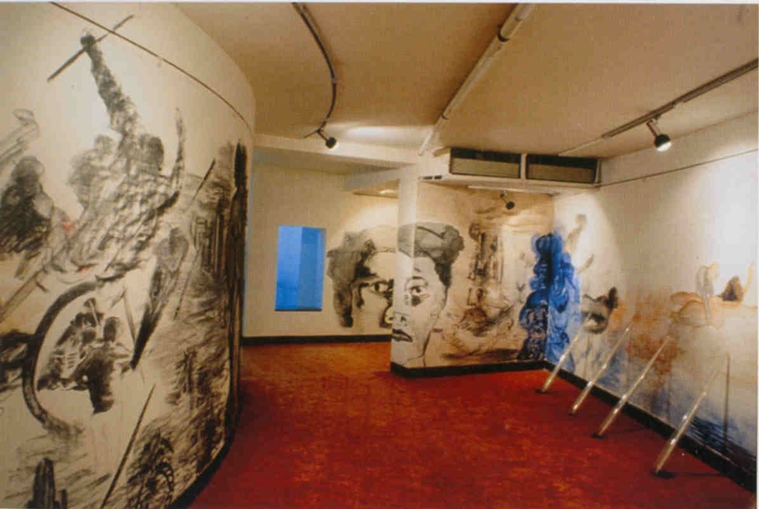

Nalini Malani, City of Desires, 1992

The artist’s first site-specific wall-drawing installation, which was on view for a limited duration at Mumbai’s Chemould Gallery, the ephemeral work was recorded for posterity in a video. Dignity in poverty of the pavement dwellers had been the subject of her work since the eighties.

Nalini Malani’s City of Desires, 1992. (Credit: Courtesy the artist)

Nalini Malani’s City of Desires, 1992. (Credit: Courtesy the artist)

City of Desires had Malani sketch live in front of a rotating audience that was also engaging with her on the narrative, from the plight of the homeless in Mumbai to the Vietnamese refugees in boats, telling of the disparities. The mural was erased in remembrance, and to mourn the loss, of a 19th century fresco at the Shrinathji Temple complex in Nathdwara, Rajasthan, that was destroyed due to neglect and vandalism. The charcoal and watercolour drawings referred to the pavement dwellers of Lohar Chawl, a wholesale bazaar, where the artist had had her studio since 1978.

Jitish Kallat, Public Notice series, 2003-2010

The series has Kallat turn to historic texts from different moments in time as reminders of the vision of our forefathers, and to assert their significance in the present times. The first was, made in 2003, had him hand-inscribe India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s famous speech on the eve of Independence, Tryst With Destiny, using rubber glue on acrylic mirror panels and setting it aflame. The work reflects on the founding ideals of the new nation — the promise of democracy, peace, unity and end of poverty and ignorance — perhaps remain an unfulfilled dream. In the subsequent works, Kallat deployed Mahatma Gandhi’s speech in 1930 on the eve of the historic Dandi March, and Swami Vivekananda’s historic speech at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, on September 11, 1893, where he addressed issues of fanaticism and encouraged universal tolerance.

Jitish Kallat, Public Notice series (2003-10), on show at GOMA, Brisbane. (Credit: Courtesy the artist)

Jitish Kallat, Public Notice series (2003-10), on show at GOMA, Brisbane. (Credit: Courtesy the artist)

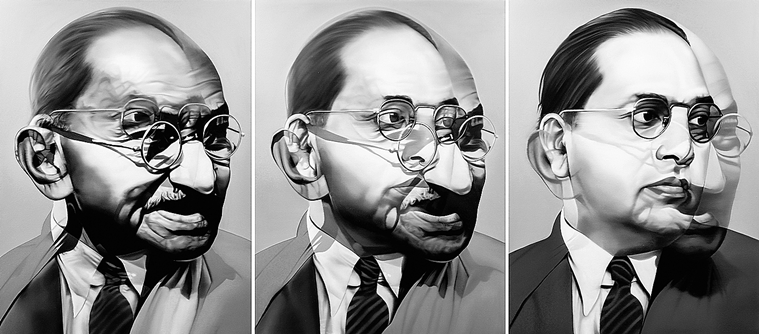

Riyas Komu, Dhamma Swaraj, 2018

The triptych superimposes the portraits of the two political leaders, Mahatma Gandhi and BR Ambedkar, to project how it is important to engage in a dialogue. By bringing together Ambedkar’s dhamma and Gandhi’s swaraj, Komu asserts that freedom cannot be exist justice and justice implies equality. “Dhamma Swaraj is a conversation. A will to dissent. It is conceived as an orientation towards future, a constructive work to invoke dialogue between the past and present, intensities of thoughts, philosophies and politics. Dhamma Swaraj does not limit itself to the frame, as Gandhi and Ambedkar as figures extend outside; it transcends to reach out to the umpteen potentials and possibilities of a shared politics of coming together as communities abandoned by ideologies of the present. These intertwined figures act as a memory of politics today with visions of acting together with difference… The figures oscillate between past and present to provide a taste of what binds and decides, what is preserved and what is decaying,” says Komu.

Riyas Komu’s Dhamma Swaraj, 2018. (Credit: Courtesy Dheeraj Thakur)

Riyas Komu’s Dhamma Swaraj, 2018. (Credit: Courtesy Dheeraj Thakur)