It still holds our imagination as a metaphor for a chimera but COVID-19 has breached the end of the earth — faraway Timbuktu in the Western African country of Mali. The city, located 1,000 km from the capital Bamako, has already seen more than 500 cases, and, at least, nine deaths, making it one of the worst affected places in the country.

The mystique of Timbuktu owes a lot to its inaccessibility, which continues even today. Located about 20 km away from the river Niger, on the southern tip of the Sahara desert, there is nothing but thousands of miles of barren desert to its north. In its heyday, the city was both a great centre of learning and a prosperous trading outpost, dealing primarily in salt, gold, cotton and ivory.

Also Read | Understanding the politics of pulling down statues: what does it convey, and what does it miss?

The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary defines Timbuktu as “a place that is very far away”. Since medieval times, the remoteness of Timbuktu, in the heart of sub-Saharan Africa, has fired the literary and cultural imagination of the West and appealed to adventurers with tales of the splendours that awaited those who managed to survive the arduous journey to it.

“The rich king of Timbuktu has many plates and sceptres of gold… he keeps a magnificent and well-furnished court… There are numerous doctors, judges, scholars, priests – and here are brought manuscript books from Barbary, which are sold at greater profit than any other merchandise,” wrote the 16th century Moorish traveller, Leo Africanus, in his definitive Descrittione dell’Africa (Description of Africa). Africanus reportedly made the journey around 1510, when the city was at its peak.

Historical accounts suggest that there have been settlements in Timbuktu since the early 12th century, when it was a local Tuareg outpost. But it soon established itself as an important serai or pit stop for camel caravans on the Saharan trade routes. According to legends, Timbuktu’s fame also spread across Europe when news of the 14th century king Mansa Musa’s opulence reached the Western world. On a holy pilgrimage to Mecca, Musa passed through the Egyptian capital, Cairo, where his largesse in distributing alms in gold coins reportedly crashed the price of gold in the land.

Timbuktu came to signify a kind of El Dorado to the outside world, a place brimming with treasures, that revealed itself only to those who were lucky enough to reach its realm. The city would reach its pinnacle under the Songhai empire, one of Africa’s most influential ruling states in the 15th and 16th century.

How Timbuktu got its name

Story continues below this ad

In the Catalan Atlas (1375), Timbuktu is referred to as “Tenbuch”. Official French documents (Mali was colonised by France between 1892 and 1960) refers to it as “Tombouctou”. While there is no definitive account of how Timbuktu got its name, in his book, Around the World in 80 Words: Journey Through the English Language (2018, University of Chicago Press), writer Paul Anthony Jones writes, “One theory claims the name might mean ‘wall’ or ‘hollow’ in the local Songhai language, while another suggests it derives from a Berber word meaning ‘sand dune’, or, ‘hidden place’.

But, perhaps, most likely of all is the theory that it derives from the name of an aged Tuareg slave woman, who was routinely tasked with guarding the Tuaregs’ camp while they roamed the surrounding desert. The woman’s name Tomboutou, is said to have meant ‘mother with a large navel’.”

A Seat of Learning

King Musa is also credited with paving the way for establishing Timbuktu as a seat of intellectual resonance. During his time in Mecca, Musa is believed to have invited religious scholars to Timbuktu to bring to fruition his plan for a new centre of Islamic scholarship.

The noted Sankore mosque in Timbuktu. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The noted Sankore mosque in Timbuktu. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Over the next several decades, it became a dynamic centre of learning and discourse, producing about 70,000 manuscripts on a wide range of topics, including Sufism, Arabic grammar, Islamic jurisprudence, philology, lexicography, astronomy and arithmetic. These manuscripts were produced in African scripts ranging from Saharan, Maghreb, Sudanese to Essouk. Mosques were built, libraries, madrasas and universities such as the noted Sankore Madrasa set up to accommodate this prodigious output.

Timbuktu in the Western imagination

Story continues below this ad

“…and thou wert then/ A centred glory-circled memory,/ Divinest Atalantis, whom the waves/ Have buried deep, and thou of later name,/ Imperial Eldorado, roofed with gold:/ Shadows to which, despite all shocks of change,/All onset of capricious accident,/ Men clung with yearning hope which would not die…” wrote Alfred Tennyson in his poem Timbuctoo in 1829.

Only a year earlier, the French explorer Rene Caillie had finally reached Timbuktu, winning a grant of 10,000 francs from the Parisian Society de Geographie, as the first non-Islamic person to reach the city and report back to the West what it really was like.

Also Read | Explained: Why we can’t easily wipe out China from India’s silk weaving industry

The Timbuktu that Caillie found was nothing like its image in the Western imagination. Once a hub of Arab-African trade, it was now a shadow of its former self. Other African cities, with far more strategic locations, had come up, and its importance as a trading post had waned.

Story continues below this ad

Even then, it would take a while for the aura surrounding it to lose its sheen. A century later, DH Lawrence would still be writing about Timbuktu in Nettles (1930): “And the world it didn’t give a hoot/ If his blood was British or Timbuctoot.”

From travel writing to fiction, Timbuktu has continued to fascinate writers. In his 1999 novella, Timbuktu, Paul Auster sets it up as an afterlife that Mr Bones, the canine protagonist, is afraid of never reaching, and, thereby, missing out the opportunity of ever being united with his dying master. Volumes have been written on the heroic efforts of its librarians to save its treasure trove of manuscripts during recent terror attacks that destroyed many of them.

Timbuktu today

But, as Auster writes in his novella, “Not all stories have happy endings”. Timbuktu today is a distant cry from what it used to be in its golden age. Still relatively inaccessible, it has been plagued by poverty, corruption, war and terrorism, following its years as a French colony.

📣 Express Explained is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay updated with the latest

Story continues below this ad

The Sahara desert has been fast breaching its boundaries, the silting of the Niger River impacting its water supply.

From 2008, acts of terrorism had impacted its fledgling tourism industry, prompting several nations to issue advisories against visiting the place. In 2012, first Tuareg-led rebels, and then, terror outfit al-Qaeda took hold of parts of northern Mali, including Timbuktu. The latter was neutralised by a French-led military operation in 2013. Peace was finally brokered in 2015 at the intervention of Algeria when the Tuareg rebels signed a peace agreement, but the region continues to remain impoverished and politically turbulent.

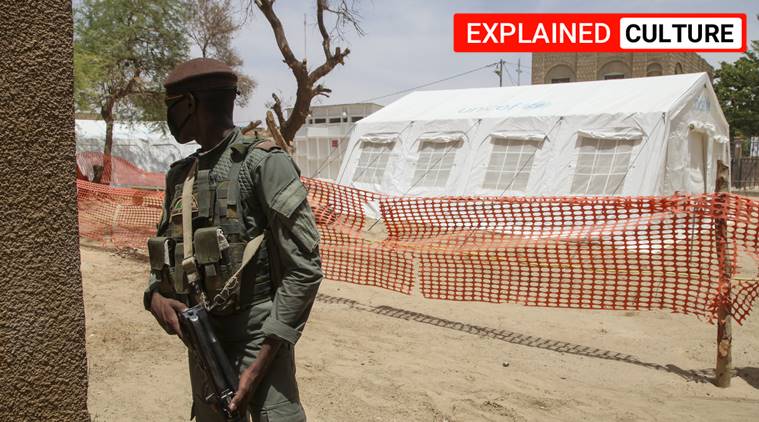

A Malian soldier stands near the isolation tent for patients with the coronavirus in Timbuktu, Mali. (AP Photo: Baba Ahmed)

A Malian soldier stands near the isolation tent for patients with the coronavirus in Timbuktu, Mali. (AP Photo: Baba Ahmed)

The noted Sankore mosque in Timbuktu. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The noted Sankore mosque in Timbuktu. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)