The notice, sent on January 25 through the Commissioner for Indus Waters, gives Pakistan 90 days to consider entering into intergovernmental negotiations to rectify the material breach of the treaty.

“This process would also update the IWT to incorporate the lessons learned over the last 62 years,” a source said.

The notice has invoked Article XII (3) of the treaty which says: The provisions of this Treaty may from time to time be modified by a duly ratified treaty concluded for that purpose between the two Governments.

Sources said India was initiating the process to make changes to the 1960 treaty.

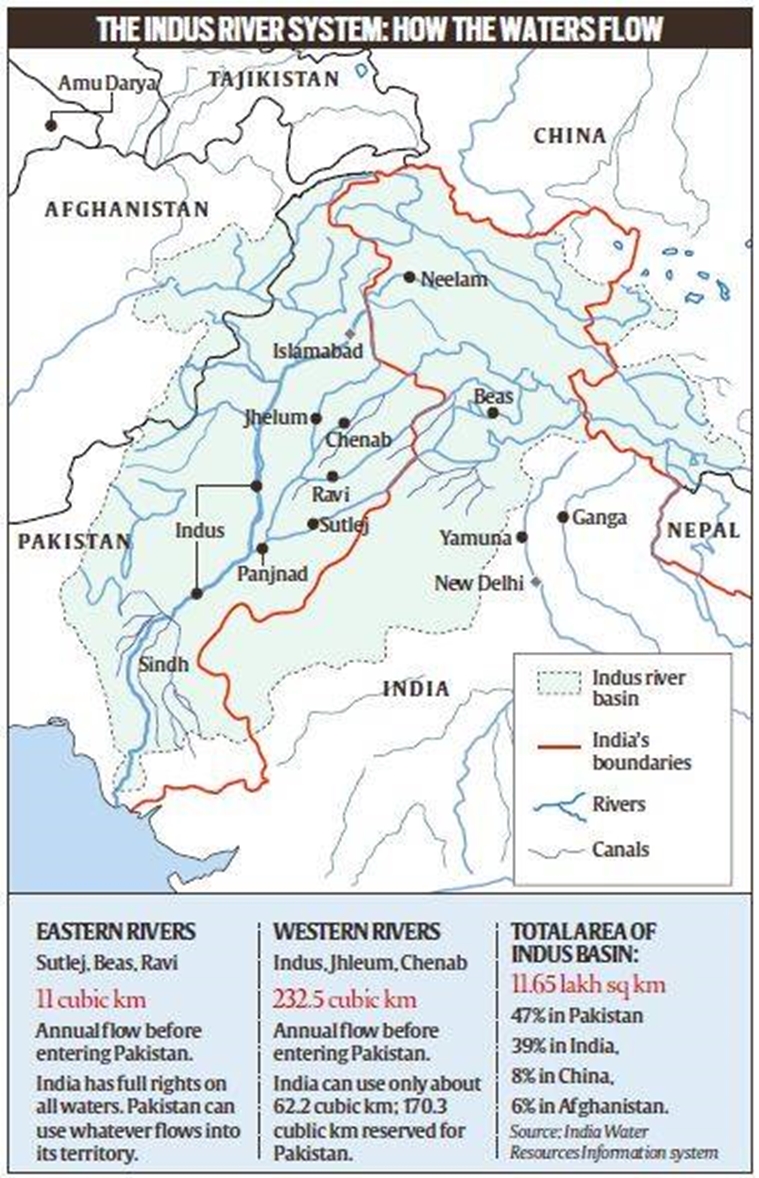

Map showing the Indus water system that is crucial for both Pakistan and Northern India. (Express Graphic)

Map showing the Indus water system that is crucial for both Pakistan and Northern India. (Express Graphic)

What is the history of the dispute over the hydel projects?

The notice appears to be a fallout of a longstanding dispute over two hydroelectric power projects that India is constructing – one on the Kishanganga river, a tributary of Jhelum, and the other on the Chenab.

Pakistan has raised objections to these projects, and dispute resolution mechanisms under the Treaty have been invoked multiple times. But a full resolution has not been reached.

Story continues below this ad

In 2015, Pakistan asked that a Neutral Expert should be appointed to examine its technical objections to the Kishanganga and Ratle HEPs. But the following year, Pakistan unilaterally retracted this request, and proposed that a Court of Arbitration should adjudicate on its objections.

In August 2016, Pakistan had approached the World Bank, which had brokered the 1960 Treaty, seeking the constitution of a Court of Arbitration under the relevant dispute redressal provisions of the Treaty.

Instead of responding to Pakistan’s request for a Court of Arbitration, India moved a separate application asking for the appointment of a Neutral Expert, which is a lower level of dispute resolution provided in the Treaty. India had argued that Pakistan’s request for a Court of Arbitration violated the graded mechanism of dispute resolution in the Treaty.

In between, a significant event had happened which had consequences for the Treaty. A Pakistan-backed terror attack on Uri in September 2016 had prompted calls within India to walk out of the Indus Waters Treaty, which allots a significantly bigger share of the six river waters to Pakistan. The Prime Minister had famously said that blood and water could not flow together, and India had suspended routine bi-annual talks between the Indus Commissioners of the two countries.

Story continues below this ad

And what happened with the two applications moved by Pakistan and India?

The World Bank, the third party to the Treaty and the acknowledged arbiter of disputes was, meanwhile, faced with a unique situation of having received two separate requests for the same dispute. New Delhi feels that the World Bank is just a facilitator and has a limited role.

On December 12, 2016, the World Bank had announced a “pause” in the separate processes initiated by India and Pakistan under the Indus Waters Treaty to allow the two countries to consider alternative ways to resolve their disagreements.

The regular meetings of Indus Waters Commissioners resumed in 2017, and India tried to use these to find mutually agreeable solutions between 2017 and 2022. Pakistan, however, refused to discuss these issues at these meetings, sources said.

Story continues below this ad

At Pakistan’s continued insistence, the World Bank, in March last year, initiated actions on the requests of both India and Pakistan. On March 31, 2022, the World Bank decided to resume the process of appointing a Neutral Expert and a Chairman for the Court of Arbitration. In October last year, the Bank named Michel Lino as the Neutral Expert and Prof. Sean Murphy as Chairman of the Court of Arbitration.

“They will carry out their duties in their individual capacity as subject matter experts and independently of any other appointments they may currently hold,” the Bank said in a statement on October 17, 2022.

On October 19, 2022, the Ministry of External Affairs said, “We have noted the World Bank’s announcement to concurrently appoint a Neutral Expert and a Chair of the Court of Arbitration in the ongoing matter related to the Kishanganga and Ratle projects.” Recognising the World Bank’s admission in its announcement that “carrying out two processes concurrently poses practical and legal challenges”, India would assess the matter, the MEA said. “India believes that the implementation of the Indus Water Treaty must be in the letter and spirit of the Treaty,” the MEA statement added.

Such parallel consideration of same issues is not provided for in any provisions of the Treaty, and India has been repeatedly citing the possibility of the two processes delivering contradictory rulings, which could lead to an unprecedented and legally untenable situation, which is unforeseen in Treaty provisions.

Story continues below this ad

What exactly is the dispute redressal mechanism laid down under the Treaty?

The dispute redressal mechanism provided under Article IX of the IWT is a graded mechanism. It’s a 3-level mechanism. So, whenever India plans to start a project, under the Indus Water Treaty, it has to inform Pakistan that it is planning to build a project.

Pakistan might oppose it and ask for more details. That would mean there is a question — and in case there is a question, that question has to be clarified between the two sides at the level of the Indus Commissioners.

If that difference is not resolved by them, then the level is raised. The question then becomes a difference. That difference is to be resolved by another set mechanism, which is the Neutral Expert. It is at this stage that the World Bank comes into picture.

In case the Neutral Expert says that they are not able to resolve the difference, or that the issue needs an interpretation of the Treaty, then that difference becomes a dispute. It then goes to the third stage — the Court of Arbitration.

Story continues below this ad

To sum up, it’s a very graded and sequential mechanism — first Commissioner, then Neutral Expert, and only then the Court of Arbitration.

What is India’s notice about, and what are its implications here onward?

While the immediate provocation for the modification is to address the issue of two parallel mechanisms, at this point, the implications of India’s notice for modifying the treaty are not very clear.

Article XII (3) of the Treaty that India has invoked is not a dispute redressal mechanism. It is in effect, a provision to amend the Treaty.

However, an amendment or modification can happen only through a “duly ratified Treaty concluded for that purpose between the two governments”. Pakistan is under no obligation to agree to India’s proposal.

Story continues below this ad

As of now, it is not clear what happens if Pakistan does not respond to India’s notice within the 90-day period.

The next provision in the Treaty, Article XII (4), provides for the termination of the Treaty through a similar process — “a duly ratified Treaty concluded for that purpose between the two governments”.

India has not spelled out exactly what it wants modified in the Treaty. But over the last few years, especially since the Uri attack, there has been a growing demand in India to use the Indus Waters Treaty as a strategic tool, considering that India has a natural advantage being the upper riparian state.

India has not fully utilized its rights over the waters of the three east-flowing rivers — Ravi, Beas and Sutlej — over which India has full control under the Treaty. It has also not adequately utilized the limited rights over the three west flowing rivers — Indus, Chenab and Jhelum — which are meant for Pakistan.

Story continues below this ad

Following the Uri attack, India had established a high-level task force to exploit the full potential of the Indus Waters Treaty. Accordingly, India has been working to start several big and small hydroelectric projects that had either been stalled or were in the planning stages.

Map showing the Indus water system that is crucial for both Pakistan and Northern India. (Express Graphic)

Map showing the Indus water system that is crucial for both Pakistan and Northern India. (Express Graphic)