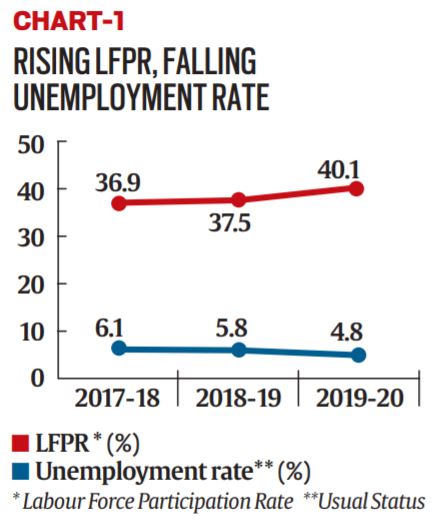

On Friday, the government released the latest annual report of the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS). The data was for the 12 months (or four quarters) between July 2019 and June 2020. It showed two surprising trends. One, India’s unemployment rate (UER) had declined over this period. Two, the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) had increased.

Over the last one decade, two of the biggest worries for Indian policymakers have been the high levels of UER and the low levels of LFPR in the economy.

The LFPR is the proportion of Indians who seek to participate in the economy. In the recent past, India’s LFPR has been less than 40% — far below the global norm (around 60%) or even the norm in most Asian counterparts such as China (76%) and Indonesia (69%). In other words, of every 100, only 40 come forward to seek work in India, while the comparable number elsewhere is around 60.

The UER is the percentage of people in the labour force who do not get employment. Again, in the last few years, India’s UER has hovered around 6% (or higher) — far more than the global or regional norm. In other words, of those 40 who chose to participate in the economy, at least 6% did not get any job.

Source: PLFS 2019-20

Source: PLFS 2019-20A combination of low LFPR and high UER then implies two things. One, India is using a much smaller proportion of its population for productive purposes. Two, the state of the economy is such that it cannot provide jobs to this relatively smaller proportion of the labour force.

The results are surprising because they correspond to a period when India’s GDP growth rate decelerated sharply; it came down to 4.2% in 2019-20. After that, the Covid-induced lockdowns further ruined the growth and employment prospects.

The context of this result is also important. The first edition of PLFS — for the year 2017-18 — had created much controversy when it showed that India’s unemployment rate had touched a 45-year high. The government tried to run down those findings as it was facing a national election in 2019, but eventually accepted the data after the elections.

Story continues below this ad

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

How did labour force participation and unemployment rates improve in a year when growth decelerated so sharply?

To unpack this, one must first understand how the PLFS collects data.

The PLFS is an annual survey conducted by the National Statistical Office (NSO). It was started in 2017 and it essentially maps the state of employment. In doing so, it collects data on variables such as the level of unemployment, the types of employment and their respective shares, the wages earned from different types of jobs, etc. Earlier, this job was done by Employment-Unemployment Surveys, but these were conducted once every five years.

Story continues below this ad

How does the PLFS calculate unemployment?

There are two ways, and they differ in terms of the reference period over which respondents have to recall whether they were working or not.

Source: PLFS 2019-20

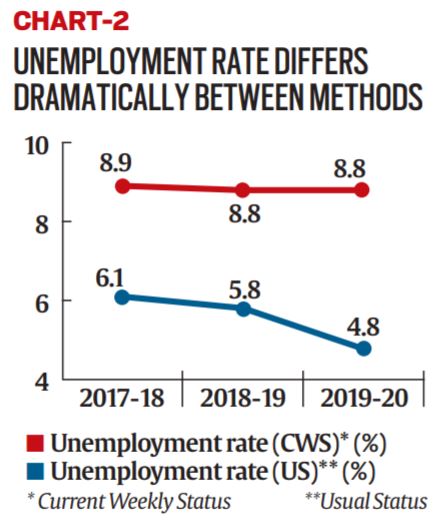

Source: PLFS 2019-20One is called the Usual Status (US). In this approach, the survey ascertains whether a person had been employed for enough days in the 365 days preceding the survey. The second approach is called the Current Weekly Status (CWS). In this, the survey tries to figure out whether a person was adequately employed in the 7 days preceding the survey.

Typically, the NSO unemployment number most routinely quoted is the one based on Usual Status. But this approach is not comparable with either the global norm (say the one followed by International Labour Organization) or the private sector practice (such as the surveys done by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy or CMIE). The CWS is closer to the global norm.

How does this help solve the riddle?

Santosh Mehrotra, who is associated with the Centre for Development in the University of Bath (UK) and has closely studied the latest data, provides two ways to reconcile these trends.

Story continues below this ad

One, with reference to the Usual Status-based data, he says the rise in LFPR and fall in UER are both explained “by the rise in distress”. Mehrotra said that if one looks at the other tables in the annual report, one finds that increased LFPR is happening because work opportunities have shrunk and incomes have fallen. He said people are being forced to take up self-employment — often of the kind designated as “helper in household enterprise” — even as the relative share of wage (or salaried) employment falls.

Two, Mehrotra pointed to the unemployment data based on CWS. “It shows no decline,” he said (Chart 2). The CWS method shows that unemployment didn’t really fall.

“Different surveys have different metrics and so a CMIE data is not comparable to the PLFS data. But still, while the magnitude may differ across surveys [that is, one survey finds higher unemployment than the other] the direction remains the same. The [UER based on] Usual Status [in the latest PLFS] is the only one that is showing a reversal in the unemployment trend,” he said.

Source: PLFS 2019-20

Source: PLFS 2019-20

But is it advisable to focus on CWS as against US?

Mehrotra said there are several reasons why India should give more importance to unemployment numbers derived from CWS.

Story continues below this ad

“For one, the memory recall is much better in CWS,” he said. The recall is less reliable over longer periods. Moreover, the nature of the Indian economy has changed. The year-long reference period of Usual Status made more sense when the economy was predominantly agrarian. Today it is not. More and more people are into jobs that do not follow a year-long schedule. The CWS is also more relevant because it is this approach NSO uses for understanding quarterly changes in unemployment.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

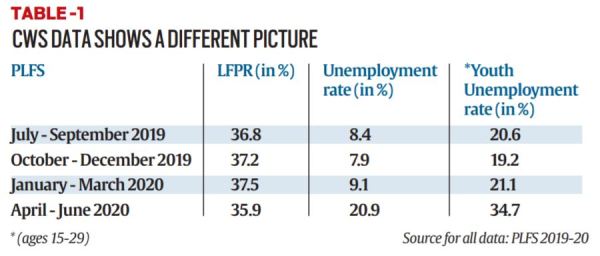

How does the picture change if we look at CWS data?

The UER and LFPR trends compiled using the CWS approach present a picture more in sync with either the data from CMIE or, indeed, from all the other indicators of the broader economy (Table 3).

We find that through the year, as GDP growth faltered, LFPR was falling further even as the unemployment rate worsened. This is particularly true for the April to June quarter of 2020 when the Indian economy was hamstrung by one of the strictest lockdowns anywhere in the world. The last column is particularly noteworthy since it shows unemployment levels among India’s youth. One in five youth failed to get a job — and this was before the pandemic.

Write to the author at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Source: PLFS 2019-20

Source: PLFS 2019-20 Source: PLFS 2019-20

Source: PLFS 2019-20 Source: PLFS 2019-20

Source: PLFS 2019-20