Sheikh Hasina sentenced to death: what happens now

Sheikh Hasina Verdict: Former Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been sentenced to death for “crimes against humanity” for her role in repressing the anti-government protests last year. What happens now?

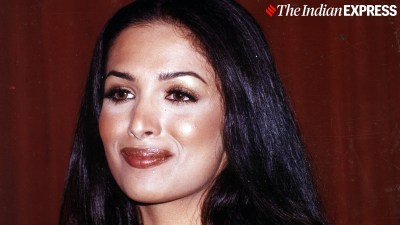

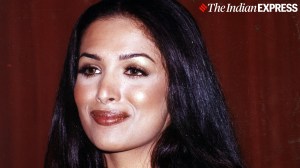

Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina speaks during a press conference in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on Jan. 6, 2014. (AP Photo/Rajesh Kumar Singh, File)

Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina speaks during a press conference in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on Jan. 6, 2014. (AP Photo/Rajesh Kumar Singh, File)Sheikh Hasina Death Sentence Explained: Former Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been convicted of “crimes against humanity” and sentenced to death by a tribunal that she herself set up in 2009 to allegedly go after political enemies.

In a 453-page judgment delivered Monday (November 17), the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) found Hasina, 78, and two co-accused guilty of allowing the use of lethal force against protesters and failing to prevent atrocities against them during last July’s protests.

Hasina’s 15-year-long rule over Bangladesh came to an abrupt end last July following months of protests against her over allegations of corruption and a deeply unpopular quota system for government jobs. She has since been living in exile in India.

Charges against former PM

The protests that rocked Bangladesh last year left as many as 1,400 people dead over a 46-day period, a report released by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in February found. Thousands more were injured.

“There are reasonable grounds to believe that officials of the former government, its security and intelligence apparatus, together with violent elements associated with the former ruling party, committed serious and systematic human rights violations,” the report stated.

After Hasina’s ouster, the incumbent government led by Muhammad Yunus promised to deliver “justice” for the crimes committed by the previous regime.

Hasina was put on trial in absentia, and five charges were brought against her (and other accused):

* Delivering inciting speeches;

* Ordering the use of lethal weapons to suppress and eliminate protesters;

* Shooting and killing Abu Sayed, a student of Begum Rokeya University in Rangpur;

* Shooting and killing six protesters in Dhaka’s Chankharpul area; and

* Burning six people to death in Ashulia.

Hasina has been convicted on all charges, The Daily Star reported; she was handed the death penalty on Count 4, concerning the shooting and killing of six unarmed protesters in Chankharpul on August 5 last year.

Hasina denies all of the charges against her. In an exclusive interview to The Indian Express last week, she blamed the current ruling dispensation in Bangladesh for the protests.

“In the early days of the protests, my government allowed the students to demonstrate freely and safely… However, matters escalated when radical elements led the crowds into violence… foreign mercenaries were present and acted as provocateurs… I have no doubt that Yunus and his followers were involved in fomenting the uprising,” she said.

Hasina’s creation turns on her

During the 2008 general election, Hasina’s Awami League pledged to try “war criminals” who collaborated with Pakistan during the 1971 Liberation War. After coming to power with two-thirds majority, Hasina established the ICT in 2009.

The tribunal went after alleged war criminals with gusto, having the full support of the public: opinion polls in Bangladesh in the early 2010s regularly ranked the setting up of the tribunal as one of the most “positive” steps taken by Hasina.

Many people were convicted in absentia; others were brought into custody and sentenced. The tribunal handed out life imprisonment and death sentences to multiple people, mostly associated with the Jamaat-e-Islami, Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party, and a major political opponent to Hasina.

While the Jamaat had undoubtedly been sympathetic to the Pakistani cause and likely participated in war crimes, critics allege that the ICT was effectively deployed as a tool by Hasina to go after political opponents.

Even neutral foreign observers questioned the legitimacy of the tribunal’s trials. For instance, Brad Adams, director of the Asia branch of Human Rights Watch, said in November 2012: “The trials against the alleged war criminals are deeply problematic, riddled with questions about the independence and impartiality of the judges and fairness of the process”.

After Hasina’s ouster last year, the very tribunal she set up — and her political opponents said was “compromised” — was quickly turned against her. Ten days after the former Prime Minister escaped Dhaka, the ICT started an investigation against 10 people, including Hasina, on charges of crimes against humanity, including murder, genocide and torture.

The prosecution submitted a 135-page charge sheet, accompanied by 8,747 pages of documents and evidence; the tribunal heard testimonies for months before giving its verdict.

Nothing changes for Hasina, for now

While significant, the verdict does not have any immediate repercussions for the former Bangladesh PM.

Hasina, who since last year has been living in an undisclosed location in Delhi, will remain in India unless New Delhi decides to agree to Dhaka’s extradition request. And that is unlikely to happen any time soon, if at all.

Hasina was an all-weather ally to India. Under her leadership, New Delhi and Dhaka saw economic, cultural, and human exchanges blossom. Moreover, unlike her predecessor Khaleda Zia, Hasina was strongly aligned to India’s security interests, going after all militant outfits who were operating in the North East from safe havens in Bangladesh.

Article 8 of the India-Bangladesh extradition treaty lists out multiple grounds for refusal of an extradition request, including cases in which an accusation has not been “made in good faith in the interests of justice” or in case of military offences which are not “an offence under the general criminal law”.

While India is yet to officially respond to Dhaka’s request, the treaty allows it enough wiggle room to issue a denial. And with a formal successor government still not in place in Dhaka — Bangladesh goes to elections early next year — New Delhi is unlikely to give in to any Bangladeshi pressure to hand Hasina back

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05