Explained: The birthright citizenship debate in the US

Here is a look at the history of birthright citizenship in the US, how it has evolved over the years, and if India automatically grants citizenship to those born on its soil

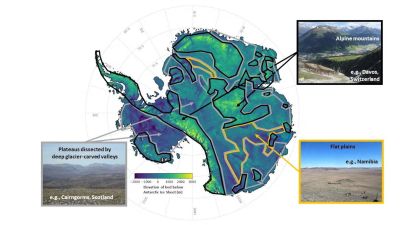

President Donald Trump holds up a signed executive order relating to science and technology in the Oval Office of the White House, on Thursday, in Washington. (Photo: AP/PTI)

President Donald Trump holds up a signed executive order relating to science and technology in the Oval Office of the White House, on Thursday, in Washington. (Photo: AP/PTI)A federal judge on Thursday (January 23) temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at curtailing the right to birthright citizenship in the United States.

The development came while Seattle-based US District Judge John Coughenour was hearing a suit filed by four Democratic-led states — Washington, Arizona, Illinois, and Oregon — which had sought to block the order before it could take effect in late February. The states argued that the order was a blatant violation of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment, which guarantees citizenship to all children born on US soil “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

Here is a look at the history of birthright citizenship in the US, how it has evolved over the years, and if India automatically grants citizenship to those born on its soil.

Origin of birthright citizenship in the US

In 1776, when the US gained independence, citizenship was largely governed by the laws of individual states. However, there was a common understanding that citizenship could be extended to all born within US territory. The original US Constitution (ratified in 1788) recognised the concept of “natural born citizens” in Article 2. Although this term was not defined, the Constitution framers likely meant it to include both “jus soli — for persons born within the country — and jus sanguinis — for persons born outside the country to American fathers,” according to Thomas H Lee, professor at Fordham Law School (US) (‘Natural Born Citizen’, 2017).

However, this right was not available equally to everyone. In Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), the US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) ruled that slaves brought to the US and their descendants could not be considered citizens.

The Dred Scott decision was rectified in 1866 when Congress passed the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, after the American Civil War (1861-1865) ended. The Amendment said, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” However, the Amendment did not end the debate on birthright citizenship as the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction” of the US led to some uncertainty. The SCOTUS stepped in to address this in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898).

Interpretations of the 14th Amendment

The case involved Wong Kim Ark who was born in the US to Chinese parents and visited China on occasion. However, upon his return from one of these visits in 1890, he was denied entry under the Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882, which prohibited Chinese immigration into the US.

In its ruling, SCOTUS held that laws passed by Congress, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, “cannot exclude Chinese persons born in this country from the operation of the broad and clear words of the Constitution”. The court also said regardless of the citizenship status of Wong’s parents, he was “subject to the jurisdiction” of the US and qualified for citizenship as a child born in the country. The court concluded that “the American citizenship which Wong Kim Ark acquired by birth within the United States has not been lost or taken away by anything happening since his birth”.

This verdict has remained the law of the land in the US ever since and will likely act as the biggest obstacle for Trump in his efforts to end birthright citizenship. The verdict has also been reaffirmed by the SCOTUS in future decisions.

For instance, in Plyler v. Doe (1982), the court affirmed citizenship rights for children of undocumented immigrants, ruling that they have a right to education. It said that according to the 14th Amendment, there was “no plausible distinction” between immigrants who entered lawfully and those who entered unlawfully as both were subject to the civil and criminal laws of the State they resided in.

Birthright citizenship in India

One of the main challenges that the framers of the Indian Constitution faced was deciding whether citizenship should be based on birth or descent. Some members of the Constituent Assembly such as P S Deshmukh (Indian National Congress Member from Maharashtra) argued against birthright citizenship, stating that it would make “Indian citizenship the cheapest on earth.”

However, other members such as B R Ambedkar and Sardar Vallabhai Patel favoured birthright citizenship, and it was ultimately recognised in the Constitution. Article 5 of the Constitution states that every person who was born in the territory before the commencement of the Constitution shall be a citizen of India.

Subsequently, Parliament enacted the Citizenship Act, 1955, which provided birthright citizenship under Section 3 to every person born in India on or after January 26, 1950. There was an exception only for children born to “an envoy of a foreign sovereign power” who is not a citizen and children of an “enemy alien” when the birth takes place in an area under enemy occupation.

However, in 1986, Parliament amended the Act to address the entry of migrants from “Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and some African Countries”. All children born after the Amendment came into force would only become citizens if either of the parents were Indian citizens, marking the end of birthright citizenship in India.

In 2003, the Act was amended again to effectively state that a child would not become a citizen at birth if one of her parents was an illegal immigrant when she was born.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05