Udit Misra is Senior Associate Editor. Follow him on Twitter @ieuditmisra ... Read More

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

Argentina's Lionel Messi celebrates with the trophy in front of the fans after winning the World Cup final soccer match between Argentina and France at the Lusail Stadium in Lusail, Qatar, Sunday, Dec. 18, 2022. (AP)

Argentina's Lionel Messi celebrates with the trophy in front of the fans after winning the World Cup final soccer match between Argentina and France at the Lusail Stadium in Lusail, Qatar, Sunday, Dec. 18, 2022. (AP) ExplainSpeaking-Economy is a weekly newsletter by Udit Misra, delivered in your inbox every Monday morning. Click here to subscribe

Dear Readers,

Lionel Messi has finally won the World Cup. One can only hope that it is the last instalment of whatever debt his genius seemed to have owed to his fans (and detractors) all over the world. Before the final match, many were of the view that it was going to be Messi against the defending champions. As it turned out, it looked more like Mbappé versus an Argentine team that seemed convinced of its date with destiny.

Anyway, with one of the longest waits in international sports over, perhaps now both Messi and the footballing world can move on. But before moving on, it matters to put on record what Messi and his team’s achievement means, especially for the Argentine people.

In one of the preview podcasts on the BBC about the FIFA World Cup, the reporter stationed in Buenos Aires said something quite remarkable as he was trying to describe the atmosphere on the streets and people’s expectations from the final on Sunday. He said the Argentinians want nothing more than Messi lifting the World Cup; in fact, the intensity of people’s wishes was so much that when asked whether they want zero inflation or Messi to win the cup, they wanted the latter.

To understand the burning desire for Messi’s win one needs to know the inflation rate in Argentina: It was more than 92 per cent in November. In other words, prices in November were 92 per cent higher than what they were in November last year. That’s close to doubling of prices. Not surprisingly, it is the highest inflation rate in 30 years.

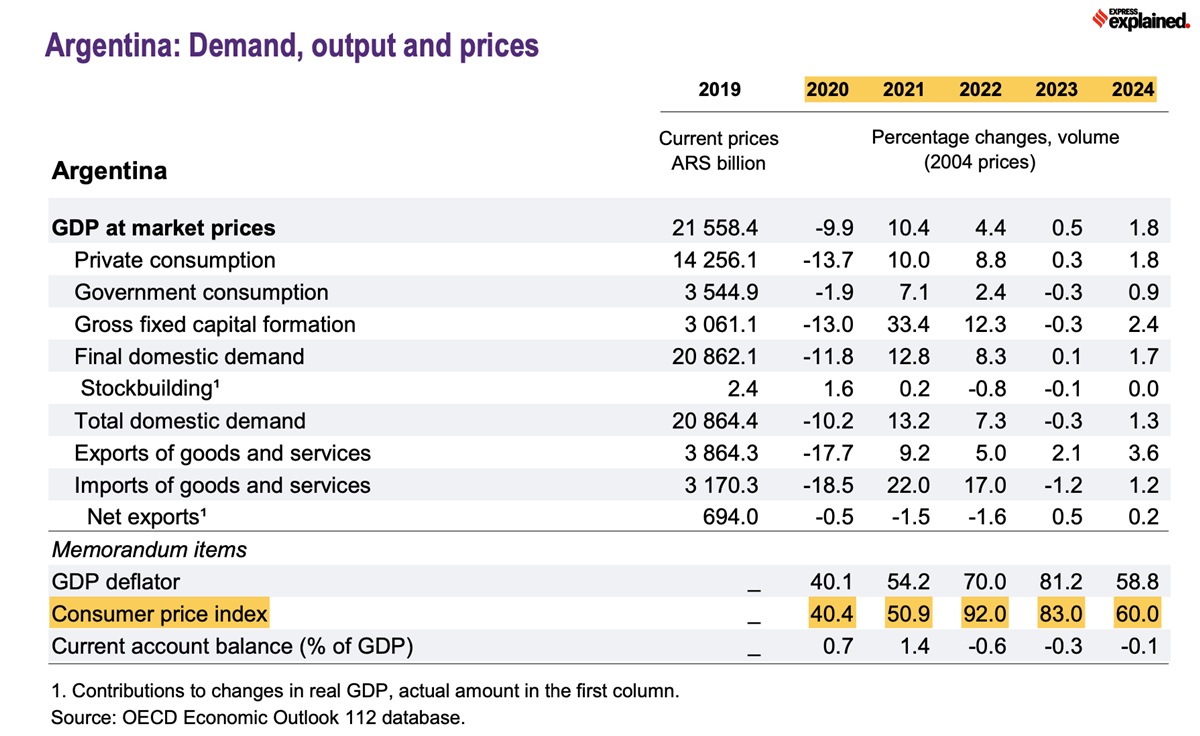

However, it is by no means just a one-off spike. The 92% inflation in 2022 was preceded by 50% inflation in 2021 and 40% inflation in 2020. Further, according to an estimate published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) last month, Argentina will continue to face an inflation rate of 83% in 2023 and 60% in 2024 (see Table 1 below).

Argentina’s GDP and Consumer Price Index (Organisation for Economic Co-operation data).

Argentina’s GDP and Consumer Price Index (Organisation for Economic Co-operation data).

In the absence of official estimates, different estimates are being used. The International Monetary Fund (see CHART 1) projects similarly high inflation rates.

High inflation rates in Argentina (IMF data).

High inflation rates in Argentina (IMF data).

To put these inflation rates in further perspective, note that the central banks of the United States and most other developed countries are effectively pushing their economies into recessions by furiously raising interest just so that they may contain inflation rates that are barely into double digits. India’a RBI has had to write an explanation to the government why it allowed inflation to spike above 6% for nine months on the trot.

In contrast, while other central banks raise interest rates “by” 75 basis points — 100 basis points make a percentage point — Argentina’s central bank has raised interest rates nine times during 2022, pushing it up “to” 75%. To be sure, RBI and US Fed talk in terms of interest rates reaching a terminal rate of 5.5%-6% levels.

If an economy grows fast, it provides some consolation for high inflation. But in Argentina’s case, high inflation is happening even when the economy’s GDP (read total output measured in $ terms) has contracted for three straight years — 2018, 2019, and 2020. In fact, Argentina’s economy contracted in four of the nine year before 2018.

CHART 2, sourced from World Bank, tells that Argentina has had a quite a chequered history when it comes to GDP growth rates. The red line highlights the zero growth rate.

Annual GDP growth rate for Argentina (World Bank data).

Annual GDP growth rate for Argentina (World Bank data).

Unsurprisingly, Argentina’s GDP has effectively stagnated, especially the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. It was $533 billion in 2008 as against $568 billion in 2021 (see CHART 3)

Argentina’s GDP from 1960 to 2021.

Argentina’s GDP from 1960 to 2021.

The economy grew by over 10 percent in 2021, thanks to a low base effect especially in the wake of the pandemic, but in 2022, it is expected to grow by just 4.5% and by just 2% odd in each of 2023 and 2024.

With population increasing each passing year, even as the economic output remains stagnant, it is only natural to find that per capita GDP will fall. CHART 4 shows exactly that. Per capita incomes have fallen to levels last seen almost 15 years ago.

Argentina’s GDP per capita from 1960 to 2021.

Argentina’s GDP per capita from 1960 to 2021.

“Poverty incidence continues above pre-pandemic levels as high inflation counteracts the effects of the relatively positive performance of the labor market,” states the World Bank’s Macro Poverty Outlook published in October 2022.

“Despite lower unemployment over the last year, economic opportunities for youth are limited—particularly among young women with low levels of education,” it further clarifies.

Currency exchange rate and foreign exchanges reserves go for a toss

High inflation, uncertain growth outlook, high fiscal deficits — all lead to investors staying away from a country’s economy.

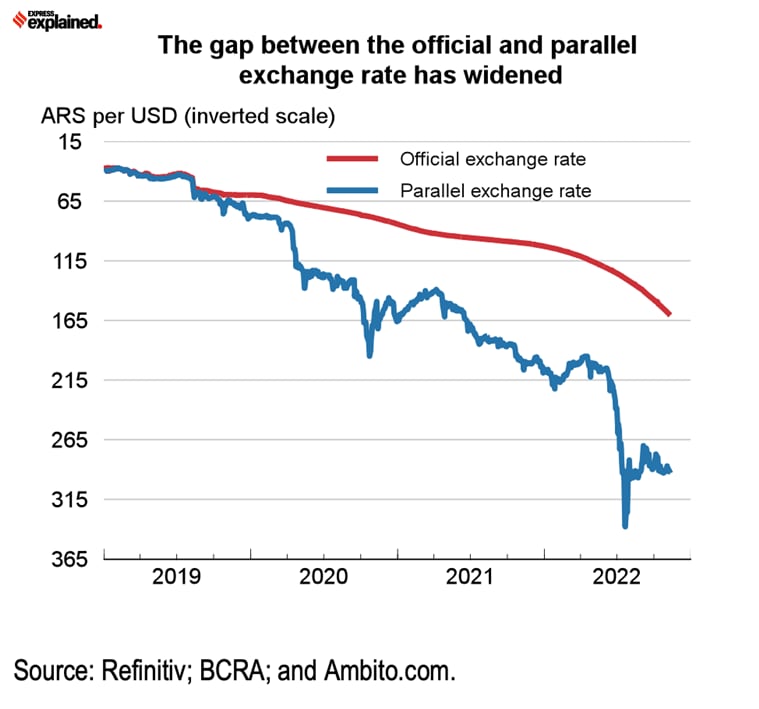

CHART 5 shows how Peso’s actual exchange rate has diverged wildly from the one mandated by the authorities. This happens when the demand for pesos on the street is so low that it cannot command the artificially set exchange rate.

ARS per USD and the gap between official and parallel exchange rate.

ARS per USD and the gap between official and parallel exchange rate.

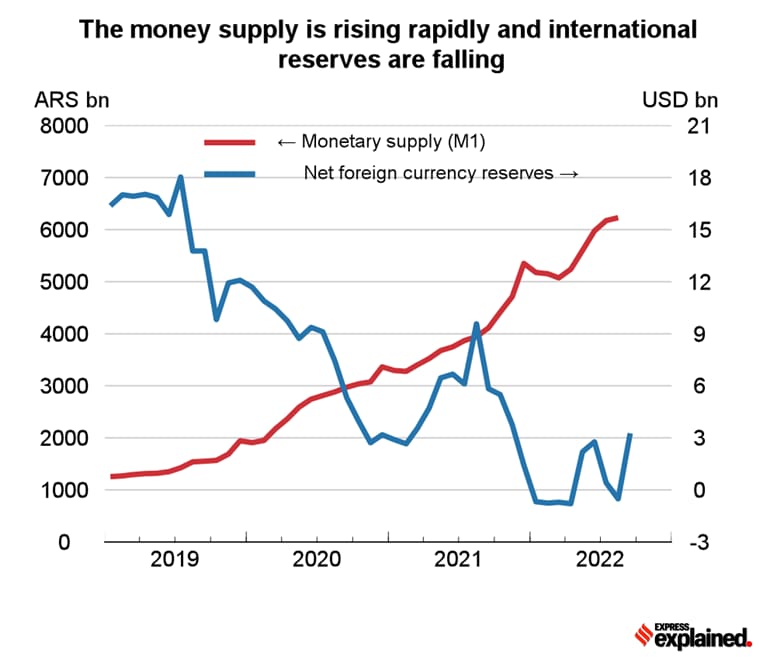

CHART 6 shows the fall in foreign exchange reserves.

Foreign exchange reserves in Argentina.

Foreign exchange reserves in Argentina.

Argentina has a long history of economic mismanagement.

But here’s what the World Bank’s latest MPO states:

“Argentina is struggling with large macroeconomic imbalances, which are slowing the pace of economic growth,” it states. “Economic activity recovered quickly from the COVID crisis and returned to pre-pandemic levels in 2021. However, output is still two percent below its previous cyclical peak and growth has slowed since early 2022,” states the OECD report.

“Budgetary rigidities and discretionary transfers contribute to fiscal deficits and their monetization, fueling inflation,” it states.

In other words, if a government doesn’t respect the budget constraint, and simply spends money (even if it has to print it), then it will simply fuel inflation; as indeed, is happening.

“Tight capital controls are leading to large gaps between official and alternative FX (foreign exchange) markets, preventing the Central Bank from accumulating international reserves, despite historically high terms of trade,” it states.

What needs to be done?

According to the OECD document, Argentina needs to usher in structural reforms to boost productivity and reduce imbalances. It points out two main issues: improving competition among private players and streamlining spending by the government.

“Improving the business environment for the private sector and strengthening competition could open up new opportunities for raising productivity and exports,” states the OECD report.

“Current attempts to improve the targeting of utility subsidies will enhance public spending efficiency, but further progress is needed to ease fiscal imbalances. Better targeting of social transfers, including reviewing tax and pension regimes, would reduce poverty and inequity while improving fiscal accounts,” the OECD assessment.

In an academic paper published in September 2022, Marco Mello of University of Surrey used OECD data, starting from 1961, to examine whether winning the FIFA World Cup boosts GDP growth.

Mello’s analysis showed that winning the FIFA World Cup increases GDP growth by at least 0.25 percentage points in the two subsequent quarters.

Why does this happen?

According to Mello, this happens “primarily driven by enhanced exports growth, which is consistent with a greater appeal enjoyed by national products and services on the global market after the victory of a major sport event”.

Instead, there are no significant effects on GDP growth for the host country.

Of course, there is no set rule about how World Cup victory will affect an economy but ask yourself a question: Which country’s jersey will be more in demand among the fans around the world? The answer will likely leave a clue.

That brings us to the close of the second last ExplainSpeaking for 2022. Watch out for the next one — the last one for 2022 — as it recaps India’s economy.

Lastly, don’t miss the latest episode of The Express Economist interviews Prof Mukesh Anand of NIPFP, where he explains why reforming the Old Pension Scheme may be India’s best bet.

Until next week,

Udit