Treacle puddings, Turkish Delights, with a side of nostalgia: foods from beloved children’s books, explained

Puddings can be savoury, and 'pastries' in the West don't mean sponge cake and cream. Here are more food items you may have read about in Enid Blyton and other books, decoded.

'When I look back at my childhood reading, I realise just how much there was that puzzled me when it came to the food.' (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

'When I look back at my childhood reading, I realise just how much there was that puzzled me when it came to the food.' (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)When I was in my late twenties, an Australian friend gifted me a copy of a book he’d adored as a child: Norman Lindsay’s The Magic Pudding, about a pudding that never diminishes, no matter how much you eat of it. What’s more, it can be whatever pudding you want. Steak-and-kidney, jam, apple dumpling.

The Magic Pudding, while ostensibly for children, is one of those books adults too can enjoy, especially as some of the humour is quite sophisticated. What’s more, at least for the average Indian reader, the adult might know more about old-fashioned British-style food than most children.

Even as I read it, I knew that if I had read this book as a ten-year-old, I would have been quite baffled by some of the food mentioned. Steak-and-kidney pudding, for one. Thanks to a mother who was fond of cooking even ‘English’ food, as it was generally dubbed back then, I wasn’t a complete ignoramus. I knew that steak and kidney were meat, and that my all-time favourite children’s author, Enid Blyton, often had her characters feasting off a steak-and-kidney pie.

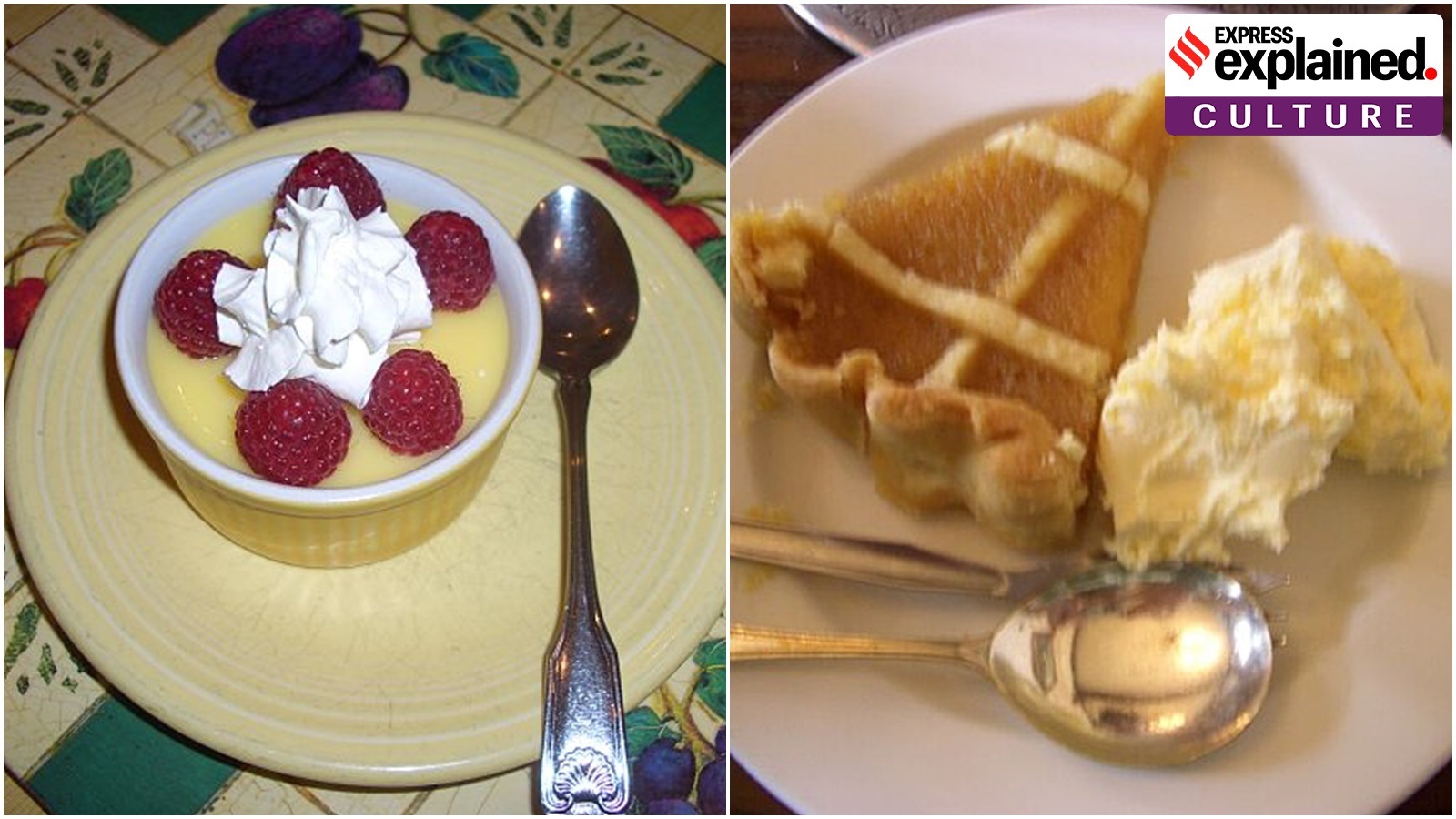

Fruit and custard, cake and jelly, all make for puddings. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Fruit and custard, cake and jelly, all make for puddings. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

But a steak-and-kidney pudding? Pudding, to me, implied dessert, or ‘sweet-dish’ (pronounced with the words running together, rather like ‘Swedish’). Something didn’t seem right here; to my mind, you couldn’t have steak and kidneys in a pudding. Fruit and custard, cake and jelly were pudding, not meat.

However, as British food historian Neil Buttery explains, ‘pudding’ is a word that’s been used in Britain since at least the 16th century, when it was essentially a sausage: a combination of meat, spices, etc. stuffed into an intestine and boiled. As time went by, puddings evolved in different ways, most importantly into steamed or baked items that were cooked in a dish. Also, while some (that steak-and-kidney pudding!) stayed savoury, a large number of sweet puddings came into being. The aforementioned jam pudding, for example; or apple pudding; or that (again seen in Blyton, to the extent of being part of the title of one of her stories), treacle pudding. If, like me, you wondered what treacle was: a thick, sweet-bitter uncrystallised syrup, which is incorporated into a sponge batter and steamed to make the pudding.

When I look back at my childhood reading, I realise just how much there was that puzzled me when it came to the food. Enid Blyton, whose books constituted about ninety-five percent of my reading before I graduated to The Three Investigators or Nancy Drew, gave a very prominent place to food in her books. Like Norman Lindsay (of The Magic Pudding, above) she too probably believed that children enjoyed reading about food; and food invariably appeared in at least one lovingly described scene in each of her books. People went picnicking; they gathered together for meals. Schoolgirls defied matrons and had midnight feasts.

And what they ate!

Here’s a glimpse, from Blyton’s Five Go Down to the Sea:

‘The larder was so crammed with food that it was difficult to get into it. Meat-pies, fruit-pies, hams, a great round tongue, pickles, sauces, jam tarts, stewed and fresh fruit, jellies, a great trifle, jugs of cream…’

The cream, fruit, jellies, the hams and even the pies, I could visualise. But pickles? For me, pickles were our local achaars, heavily spiced and liberally soaked in oil, not at all the sort of accompaniment I’d have expected to a typically British meal as this. It was only many years later that I realised that Western pickles were staid ones, basically vinegar and salt, perhaps some sugar; if adventurous, mustard seeds, peppercorns, or possibly dill. No chillies, no masala.

And tongue. I was sure this was something else; it couldn’t literally be a tongue. But it is: beef tongue or ox tongue is offal, a cut of beef that is cooked and sliced and used like ham.

Scrumptious: a jam tart. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Scrumptious: a jam tart. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

I was lucky that my mother actually made trifle and jam tarts at home, otherwise those, too, would have been a mystery to me. As it was, the scones flummoxed me. I pronounced them to rhyme with cones, not realising that they might properly be rhyming with cons (the verdict is out on this, though; even in England, there are regional variations in pronunciation). And I had no idea what these were supposed to be. Given that all the stories had people eating them with cream and jam, I assumed they were a type of cake. No; more like biscuits, puffy discs of light, crumbly pastry. Also, I discovered that what we regarded as ‘pastry’—pineapple pastry, chocolate pastry, et al—was not at all what Blyton and her ilk referred to as pastry. To the West, what a pie is encased in is pastry: a rich, fat-laden, dense baked dough. Sponge cake and cream do not a pastry make.

Children’s literature threw other googlies at me in food terms. The Turkish delight of The Chronicles of Narnia? Also known as lokum, this is a chewy, vividly coloured confection from the Mediterranean (not just Turkey), typically flavoured with rosewater.

Turkish Delight is a chewy, vividly coloured confection from the Mediterranean. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Turkish Delight is a chewy, vividly coloured confection from the Mediterranean. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

There’s potted meat (canned, cooked meat, often preserved in a thick layer of fat) and ginger beer (a fermented, fizzy ginger-flavoured drink, with fairly negligible alcohol levels) from The Wind in the Willows. From Alice in Wonderland, liquorice comfits: candied bits of aniseed-flavoured liquorice root, coated in sugar, startlingly similar to the multicoloured aniseed that is still so popular here in India as a mouth freshener.

The list goes on and on: of foods encountered in foreign literature, some even now unknown here. Some that have gradually become familiar (mince pies, which I always thought were the English equivalent of keema samosas and which actually turned out to be sweet, spiced mixes of Christmassy dried fruit and nuts, are now available at fancy bakeries). Some that will perhaps never make their way here. Some that will always remain enticing only on paper, making young readers salivate even though they don’t really know what they’re hankering after.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05