Sweet Nothings: Searching for a Diwali staple in Delhi’s Gali Batashe Wali

As children, Diwali meant a world of rituals. In our home, it began with extinguishing all the lights as soon as evening fell. In the darkness, a single diya was lit in the puja room, following which the whole house was lit up to draw in Goddess Lakshmi. As with every ritual, there were rewards. […]

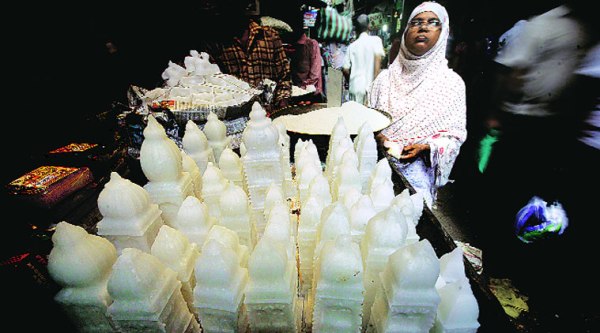

Sweet Tooth: A shop at Gali Batashe Wali

Sweet Tooth: A shop at Gali Batashe Wali

As children, Diwali meant a world of rituals. In our home, it began with extinguishing all the lights as soon as evening fell. In the darkness, a single diya was lit in the puja room, following which the whole house was lit up to draw in Goddess Lakshmi.

As with every ritual, there were rewards. For Diwali, it was batasha. We needed an incentive to scamper around the house, hang marigold garlands and design the rangoli. In Delhi, for several generations, that reward was sourced from a small bylane in Purani Dilli, fittingly named “Gali Batashe Wali”.

An offshoot of the famed spice market, Khali Baori, Batashe Wali Gali is a small twisting bylane populated mainly by soap stores (stocking washables ranging from coarse to fine, gritty to surf-like excellence). At one time, it was home to “at least 25-30 batasha shops”, according to Sumit Goyal, scion of Surendar Goyal and Sons, an establishment which has been dispensing the crystalline sweet for the last 50 years. Dwindling business now has seen many shops switch from batasha to other sweetmeats. “We still retail batasha round the year, but the peak season is Diwali,” he says. This time, demand precludes variations such as Khilone (shaped like animals) and Hathri (tower-shaped and styled sugar confections ranging from six inches to two feet), apart from the conventional drop-shaped batasha.

While earlier batasha was bought in large quantity, it is now just a small part to be used as prasad. “Earlier, we didn’t even attempt to quantify the amount of sugar used, but at a rough estimate, we would easily sell about 10,000-15,000 kilos during Diwali. Now that number has shrunk to about a 1,000-1,200 kilos,” says Vinod Kumar of Vinod Kumar and Sons sweet shop. “Because of health concerns, such as diabetes, people buy limited amounts. Earlier, people used to buy by the kilo, now they just pick by the pao (250 gms), or even lesser,” he says.

These calorific concerns have, literally, bitten into the profits earlier enjoyed by the vendors, prompting them to take up alternate businesses. While Kumar has been retailing different varieties of sugar crystals, Surender Goyal and Sons have been dealing in biscuits, petha and other sweetmeats. Many others have diversified into spices. Both vendors, among the largest in their category in the lane, have not much hope for the future. “Batasha ka demand toh girta hi jaaega, yeh hum sabko pata hai. Woh healthy bhi nahin hai aur log apni parampara toh waise hi bhool rahen hain,” says one vendor, now operating out of a small alcove. It probably doesn’t help that now batasha is available readily at all neighbourhoods.

For us, the memory of childhood trumped reason. Half a kilo batasha and an immeasurable amount of happiness later, Batasha Wali Gali transmuted into a treasure-drove to be plundered again and again. Cavities be damned.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05