As the BJP tries to distance itself from party MP Nishikant Dubey’s comments on the judiciary, the Jharkhand parliamentarian has set off a fresh row on the subject.

Dubey took to X on Tuesday to talk of a “funny story” about the “Congress’s Save the Constitution” narrative.

He claimed that a judge named Baharul Islam from Assam was still a part of the judiciary when he got associated with the Congress. And when he was elevated as a Supreme Court judge, Dubey added, Islam “dismissed all the corruption cases against Indira Gandhi from the time of the Emergency”.

The Congress hit back, with senior leader Pawan Khera saying that the “political exploitation of the judicial process, courts, and judges by the RSS, Jana Sangh, and BJP is recorded in the pages of history.”

Khera also claimed that BJP precursor Jana Sangh’s leader Guman Mal Lodha had held judicial appointments even as he was actively involved with the party. And that former Supreme Court justice K Subbarao resigned from his post “under pressure” from Jana Sangh leaders.

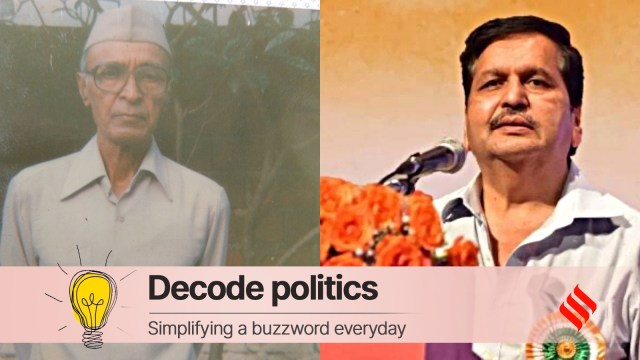

Baharul Islam, the SC judge who contested an election

Islam enrolled as an Advocate of the Assam High Court in 1951. Eight years later, he made his way to the Supreme Court for his practice.

The Congress gave him a Rajya Sabha membership in 1962, and reappointed him again in 1968. In 1972, he resigned as an RS MP and, the same year, was appointed a judge of the then Assam and Nagaland High Court, which was later renamed the Gauhati High Court.

Story continues below this ad

Subsequently, he was appointed the Chief Justice of the Gauhati High Court on July 7, 1979. He retired on March 1, 1980. Months later, he was appointed a judge of the Supreme Court. He took over on December 4, 1980, and was due to retire on March 1, 1983.

In January 1983, two months before his tenure was to end, Islam submitted his resignation as a judge of the apex court to contest a Lok Sabha seat as a Congress (I) candidate from Barpeta in Assam. This was shortly after he had decided in favour of then Bihar Chief minister Jagannath Misra of the Congress (I) in a controversial case about “misuse of office”.

In Supreme Whispers: Conversations with Judges of the Supreme Court of India (1980-89), lawyer Abhinav Chandrachud’s writes that Chief Justice Y V Chandrachud (1978-1985) had considered his decision to sign off on Islam’s appointment the “low point in the history of Supreme Court appointments”.

“(Then) Law Minister P Shiv Shankar had pressed Chandrachud hard on Islam’s appointment and said that there would be ‘no harm’ in appointing him. Chandrachud had agreed,” the lawyer writes in his book.

Story continues below this ad

Gumanmal Lodha, a High Court judge who became a three-time MP

Lodha, from the Nagaur district in Rajasthan, was a dedicated RSS worker who went on to become the state chief of the Jana Sangh between 1969 and 1971. He was also an MLA from Rajasthan in the 1972-77 Assembly session.

Between 1978 and 1988, Lodha served as a judge of the Rajasthan High Court. He became the Chief Justice of the Gauhati High Court but served in the position for just 15 days. He resigned on March 15, 1988.

In 1989, a year after his resignation and eight years after the BJP was formed, he was elected to the Lok Sabha from Pali in Rajasthan. He became a member of the BJP National Executive the same year. In 1991, Lodha was re-elected to the Lok Sabha and won Pali again in 1996.

His son Mangal Prabhat Lodha, the industrialist, is currently the MLA from the upscale Malabar Hill constituency in South Mumbai.

Story continues below this ad

K Subba Rao, the CJI who resigned in protest

Rao took charge as the CJI on June 30, 1966. He resigned within just a year of assuming office and the circumstances under which he left office generated a lot of talk at the time.

In February 1967, Rao led the majority in “handing the (then Indira Gandhi) government a defeat in the Golaknath case,” writes legal scholar George H Gadbois in his book Judges of the Supreme Court of India (1950–1989).

The judgment said that Parliament had no authority to take away any fundamental rights. This, Gadbois writes, “was one of the most significant constitutional law decisions in the Court’s history up to that time”.

The same month saw the fourth parliamentary elections in which the Congress returned to power by winning 283 seats. Two months later, on April 11, came Rao’s resignation.

Story continues below this ad

Rao, considered one of the most outspoken judges on matters of fundamental rights, was invited by the United Opposition — of which the Jana Sangh was a part — to be a candidate for the presidency in 1967.

The Congress was still the dominant force even though it was seeing a challenge. Rao accepted the nomination for the presidential polls. However, he was defeated by the Congress’s Zakir Hussain.

How the current controversy started and spiralled

Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar triggered a debate on the issue last week, saying India cannot have a situation where the “judiciary directs the President”.

Dhankhar’s comments were criticised by several in the Opposition.

Story continues below this ad

On Saturday, Dubey said current CJI Sanjiv Khanna was responsible for “all civil wars in the country”.

BJP MP Dinesh Sharma also added to the chatter and said that the judiciary “cannot direct the President”. The BJP was quick to distance itself from the remarks.

On Tuesday, Dhankhar said Parliament was supreme, with elected representatives being the final arbiters of the Constitution.