Opinion UGC guidelines for PhD, predatory journals, university rankings: Why we need to ring the alarm bell

The tendency to equate research quality with a number of citations and further connect it to the reputation of a scholar is a matter of concern. The real challenge is how to strengthen the research culture in Indian universities

While publications and citations are relevant for evaluating the quality of research, their numbers are by no means a direct measure of quality. (Wikimedia Commons)

While publications and citations are relevant for evaluating the quality of research, their numbers are by no means a direct measure of quality. (Wikimedia Commons) Written by Bhushan Patwardhan and K P Mohanan

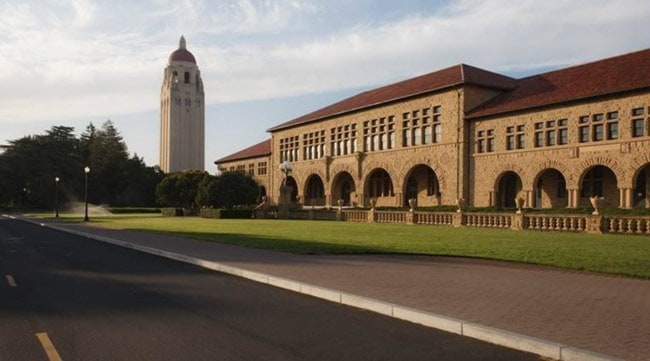

There has been a sudden surge of self-congratulation among scientists belonging to the top 2 per cent of the Stanford University Rankings 2022. The rankings are based on the project “Updated science-wide author databases of standardised citation indicators” by John Ioannidis, Kevin Boyack, and Jeroen Baas from Stanford University, which offers a valuable database of citations. However, data is not the same as a conclusion or judgement. This exercise is part of data analysis and cannot be taken as a statement of the ranking of the scientist’s quality of research in the world. Another danger of the viral hype of the top 2 per cent of scientists is its over-emphasis on STEM excluding the other domains of knowledge. This too is detrimental to the idea of holistic education recommended by the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

The citation data is certainly important; however, it should not be considered a measure of the research quality. The citation number simply indicates how many times peers have cited a particular article. The tendency to equate research quality with a number of citations and further connect it to the reputation of a scientist is a matter of concern. Since one of the two authors of this article (Patwardhan), features in the top 2 per cent according to the list, we feel entitled to ring alarm bells about that conflation.

Why are we alarmed? Because citation index data, like any data, need to be properly interpreted. The number we extract from the data is by no means a measure of the quality of the research. This has become extremely important in today’s research world where predatory journals have become a global menace. The Consortium for Academic Research Ethics (CARE) established by the University Grants Commission (UGC) states, “Increased incidence of compromised publication ethics and deteriorating academic integrity is a growing problem contaminating all domains of research. It has been observed that unethical / deceptive practices in publishing are leading to an increased number of dubious/ predatory journals worldwide. It has been reported that the percentage of research articles published in predatory journals is high in Indian Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs). Unethical practices leading to ‘pay and publish trash’ culture in India needs to be thwarted immediately.” The UGC’s notification with new guidelines for PhD this week addresses only a small part of the big problem. The real challenge is how to strengthen the research culture in Indian universities. It is expected that any good doctoral research should be a quest for truth, adding to the existing body of knowledge. It should not be done just for the sake of a degree like a PhD to get a job, promotion, recognition, prestige, publications, patents, etc., although these may emerge as natural outcomes. It is also important to distinguish between regulations that prevent lowering of quality, which often become forms of policing, and initiatives like CARE that help improve quality, becoming agents of empowerment.

Any interpretation of the quality of research that uses data on the number of publications and citations must be grounded in an awareness of Beall’s List of potential predatory journals and publishers. Mamidala Jagadesh Kumar, Chair of UGC and ex-vice chancellor of Jawaharlal Nehru University in a recent article points out that focusing on publications instead of the quality of research is equally dangerous in PhD programmes. In a recent study at a top university, it was observed that because of the mandatory condition by the UGC to publish a paper before PhD thesis submission, nearly 75 per cent of the students were tempted to publish in poor quality / predatory journals.

Going beyond predatory journals, it is also well-known that the reviewers of refereed journals use their position to increase the number of citations to their own work. Retractionwatch.com has over 30,000 retractions in its database. This indicates the prevailing trend of rampant violations and compromised research integrity in the community of funders, sponsors, supervisors and others in positions of power who use those working under them to boost their own business, CV, citations, and popularity.

This situation is not very different from the relation between student feedback scores and quality of teaching. The student feedback scores are a measure of the popularity of a teacher, not a measure of the quality of teaching. Likewise, the score in the UGC National Eligibility Test (NET) used for admission to PhD programmes or eligibility to become academic faculty is a measure of hard work and exam-cracking skills, not a measure of research or teaching capability.

These examples show that while publications and citations are relevant for evaluating the quality of research, their numbers are by no means a direct measure of quality. Ultimately, a judgement of the quality of research is subjective. Whether a dissertation deserves a PhD is a matter of the informed judgement shared by the members of an expert committee who are assumed to be competent. Whether an article submitted for publication should be published is a matter of similar judgements of editorial board members. In both cases, it is assumed that the experts not only have adequate expertise but also adequate ethical integrity. However, when assumptions of the jury’s expertise and integrity turn out to be dubious, or when incompetence and corruption are rampant, we need to set up a system of checks and balances to ensure the credibility of experts’ judgments. Thus, any system of assessment and accreditation for higher education institutions is bound to fail if only numbers are used as measures of quality. This concern motivated us to write the recent Whitepaper, “Reimagining Assessment and Accreditation” (Whitepaper 2022) published by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC).

The very purpose of research and also education is compromised when the NAAC accreditation letter grades or world university rankings by THE or QS are used as marketing tools to project an institution’s image linked to the quality of education. Using the databases of standardised citation indicators as a measure of the quality of research, that too linked to the reputation or ranking of scientists, whether done by Stanford or some other university, would compromise the drive — initiated by the Whitepaper 2022 — to raise the quality of research, education, and student learning.

The best measure of the quality of higher education is its long-term effects on the future of learners. The best measure of the quality of research is its long-term effects on the future of knowledge and relevance to society. A rat race to get to the top rungs of world ranking is neither good for universities nor scientists, unless the basic purposes of both are served.

Patwardhan is National Research Professor, currently Chairman NAAC Executive Committee and former Vice Chairman, UGC. Mohanan is a founding member of THINQ who taught at MIT, Stanford, NUS and IISER Pune

(Disclaimer: The views in the article are personal)