Opinion EWS reservation: Recognising the poor

Dr Ashwani Kumar writes: Economic deprivation, with its attendant consequences, must be addressed as part of the government's affirmative action policies for empowerment of the poor, not covered by caste-based reservation. The verdict in the EWS case is in keeping with the vision of a dynamic Constitution with equity at its heart.

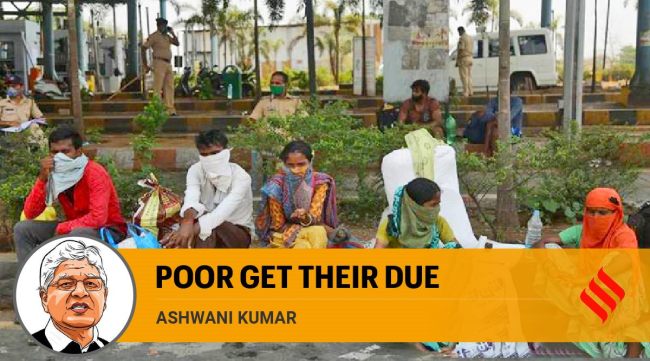

The defining logic of the majority view, also accepted in principle by the minority, is that the debasing impact of poverty on human dignity is caste neutral. (Express Photo: Prashant Nadkar, File)

The defining logic of the majority view, also accepted in principle by the minority, is that the debasing impact of poverty on human dignity is caste neutral. (Express Photo: Prashant Nadkar, File) The Supreme Court’s majority judgment in Janhit Abhiyan is a watershed moment in the nation’s endeavour to advance inter-generational justice. It views reservation in government employment and educational institutions as a tool of affirmative action and reparative justice, beyond identity and representation. Endorsing the 103rd constitutional amendment, the Court has expanded the sweep of affirmative action by extending the benefit of quotas to the hitherto excluded economically weaker sections (EWS) of the “forward classes”. It repelled the legal challenge to the amendment, mounted principally on the ground that reservation on the basis of economic backwardness alone was a species of class discrimination constitutionally impermissible and violative of the Constitution”s basic structure (Kesavanand Bharti, 1973). The Court also rejected the argument that the exclusion of SCs, STs and the non-creamy layer of OBC’s from the 10 per cent reservation was discriminatory and that the amendment breached the judicially-mandated 50 per cent cap on reservation. The majority thus endorsed the central premise of the amendment — economic deprivation, with its attendant consequences, must be addressed as part of the government’s affirmative action policies for empowerment of the poor, not covered by caste based reservation.

The defining logic of the majority view, also accepted in principle by the minority, is that the debasing impact of poverty on human dignity is caste neutral. Indeed, the ravages of history and histories of marginalisation including our own experience as an oppressed colonial nation tell us that “calculated oppression” is a function of economic deprivation that scars the soul in a dehumanising perpetuation of poverty. An acute awareness of the social and economic inequities that have inspired the Constitution’s preambular promise, elaborated in the inter-play of Directive Principles (Articles 38, 39A, 46) and Fundamental Rights provide the edifice for the Court’s majority judgment. In upholding the challenged amendment, the majority reasoned that reservation was an exception to the equality principle and therefore, not a part of the basic structure of the Constitution. It could thus be modulated for the benefit of those not already availing of the benefits of affirmative action. It held that the new beneficiaries could be treated as a distinct and separate category for the purpose of reservation with reference to the twin constitutional tests of rational differentiation and the object sought to be achieved. Breaching of the 50 per cent cap on reservation has been justified on the basis that it was judicially conceived only in respect of the backward classes and is not “inflexible and immovable for all times to come”.

Recalling its judgment in N M Thomas (1976) and logic of the Punjab and Haryana High Court in Jagdish Rai (1977), as also the dissenting judgment of Chief justice of Patna High Court in Sudarshan Thakur (1957) endorsing the State’s power to provide reservation in case of “undeserved want”, the Court rejected “the tying (of) substantive equality to a fixed category of backwardness”. It recognised “a constantly evolving situation where groups that are the sites of social and institutional disadvantages can change over time and even new groups can be added as times change”.

In a compelling construct of the nation’s democratic arrangement enshrined in a dynamic Constitution, the Court affirmed that each generation must invest the document with new content to make it a “living organic thing”; “not bound to be understood or acceptable to the original understanding of the constitutional economics…” (Association of United Tele services Providers, 2014). The majority view builds upon a stated deference to Living Tree Constitutionalism and unfolds an expansive judicial gaze upon the Constitution, not frozen in time, to ensure its continuing relevance in the advancement of national goals. The majority decision affirms that in a parliamentary democracy, policy choices representing the harmonising of conflicting interests through pragmatic adjustments is essentially a legislative function that ought not to be overridden by judicial fiats, unless plainly offensive to the Constitution.

However, in a never-ending process of justice, the split verdict in the case will keep the competing arguments alive on complex questions at the intersection of law and politics. For the moment, the majority view with its precedential value must hold the field. Legal finesse apart, the distinction of the majority view rests upon its exposition of an idea of constitutional justice consistent with current popular sensitivities and aspirations and is grounded in “reasoned engagement”. It addresses the disquiet amongst the economically disadvantaged sections at being excluded so far from the orbit of the state’s empowering policies, validating thereby the Constitution’s stabilising function through the redressal of remedial injustices.

Political parties, reportedly having politically expedient second thoughts on the validity of the amendment, even after unreservedly supporting its passage in Parliament, must know that politics based on compromised principles inevitably fails. And only those who appealed to “the brooding spirit of the law, to the intelligence of a future day…” post Indra Sawhney (1992), can now claim vindication.

However, for the new architecture of “compensatory discrimination” scripted by the majority in Janhit to endure, it is necessary to ensure that reverse discrimination is not stretched to a point where it “eat(s) up the rule of equality”. This is a burden of statesmanship and of the quality of our democratic politics. In the final analysis, constitutional doctrines and changes in the temper of intellectual speculations reflect the fluctuating conditions of social, economic and political life. B R Ambedkar’s reminder that “the spirit of the Constitution is the spirit of the age”, is the unmistakable message of the majority judgment in the Janhit case.

The writer is Senior Advocate, Supreme Court and former Union Minister for Law & Justice. Views are personal