Opinion Bharat Jodo Yatra: Reaching the journey

Peter Ronald deSouza writes: The Congress's yatra has much to learn from the previous yatras

Peter Ronald deSouza writes: The Bharat Jodo Yatra has much to learn from the previous yatras.

Peter Ronald deSouza writes: The Bharat Jodo Yatra has much to learn from the previous yatras. Tour the length and breadth of the country, “with eyes and ears open, but mouth shut”, was the advice given to Gandhiji by Gopal Krishna Gokhale. This is how he would learn about India, its peoples, cultures, challenges, and aspirations on his return from South Africa – by going on a yatra. Gokhale was making the obvious point that seeing and hearing are two of the primary ways to know the world. But when he advised Gandhiji to keep his “mouth shut” he was making a subtler point. Let the people speak, he seemed to be counseling. Do not lecture them, for you do not have all the answers. They have something to tell you. Gandhiji followed this sage advice, and as a result India got a new vocabulary of politics.

Jawaharlal Nehru also undertook a yatra, but of a different kind. It was a mental yatra through Indian history as he wrote, in five months, while in prison in Ahmednagar jail from 1942-46, his voluminous 700-page book, The Discovery of India. He marvelled not just at India’s ancient land but also at its culture and philosophy. People have criticised him for the word “discovery” in the title, saying that no Indian needs to discover India, only outsiders do. Indians know India. This is a superficial and vacuous criticism for it has no understanding of the philosophical complexity of India, its cultural diversity, geographical variety, and long history. India’s layered reality can, in fact, only be known through many lifetimes of continuous discovery. That is what makes it so magical. Try understanding the significance of the 300 Ramayanas that AK Ramanujan mentioned and you will see how complex and how delightful India is. A regular yatra of the mind is certainly required in India.

Closer to our time, Chandra Shekhar undertook a 4,260 km six-month padayatra, later called Bharat Yatra, from Kanyakumari to Rajghat in 1983. In the Commemorative Volume published by Parliament, he says of his yatra: “When we started, it was doubtful whether people would react positively to Bharat Yatra or would take it as a political drama. But all through the yatra, the villagers who were illiterate, who were ignorant, who were helpless, lined up in large numbers to receive the volunteers who were walking. In almost all the villages, even the poor people managed to offer the best welcome that they could afford. There might have been difficulty of language, but the language of the heart, which was more powerful, helped to communicate the feelings. We ourselves understood that the people are willing to cooperate if we go to them. In this respect, it was Mahatma Gandhi who put his finger on the pulse of the people. It was an adventure in self, it was an adventure of self-education.”

Chandra Shekhar was anxious that the yatra would be seen as a political drama but it grew, instead, into the “language of the heart” as people lined up to connect with the leader. For Chandra Shekhar, the yatra turned out to be “self-education”. It raised his political profile, gave him moral authority. The power of the yatra as a tool of political mobilisation was later successfully used by NT Rama Rao, who launched the Telugu Desam Party after his yatra across Andhra Pradesh, and YSR Reddy who walked nearly 1,500 km across AP. Both won the assembly elections that followed. From a different political perspective, LK Advani embarked on a Rath Yatra that converted the demand to build a Ram temple in Ayodhya into the dominant discourse of contemporary India. Now, three decades later, it remains the pivotal idea of the NDA regime’s politics of mobilisation.

“Yatra” is one of the key ideas that India has contributed to the global democratic lexicon. It is a unique instrument of political mobilisation. Few leaders across the world have undertaken yatras, preferring air and road-hopping trips instead. The yatra is a powerful strategy to build a counter discourse on all things concerning the nation. Because it is peaceful, and because it is slow, it allows a prolonged engagement with the concerns of the political. It reduces the gap between the leader and the citizen, since its spatial and temporal attributes — one has to travel through remote villages and ignored habitations — bring it closer to the people. This can serve to produce a political excitement that change is coming, that better times lie ahead.

The Bharat Jodo Yatra has much to learn from the previous yatras. Build a new imagination for India, as was achieved by Gandhiji’s yatra. Learn about India’s rich history and cultural diversity, as bequeathed by Nehru’s yatra. Listen to the people with humility (shut up and listen), was the lesson of Chandra Shekhar’s yatra. And produce a counter mobilisation to the power of the entrenched regime, as was done by the yatras of NTR, YSR, and Advani.

Of course, there will be adverse comment. This is legitimate in a democracy. The NDA and its formidable media cell will employ every trick in the book to mock the Bharat Jodo Yatra, ridiculing its leaders, obstructing its progress, and belittling its goals. This has already begun. It will get more intense as the power of the digital world will be harnessed to diminish its possibilities. But India needs an alternative discourse to that of the politics of othering, which, in its best version, is what the yatra offers. The yatra is potent because it will show how far the rulers have moved from the people, and how dismissive they are of the people’s concerns. It carries the seeds of change which have to be carefully nurtured, if it is to win the support of the people. We live in a digital world and therefore capturing the symbolic high ground, in visuals and text, is vital. Like the farmers’ protests did in 2021.

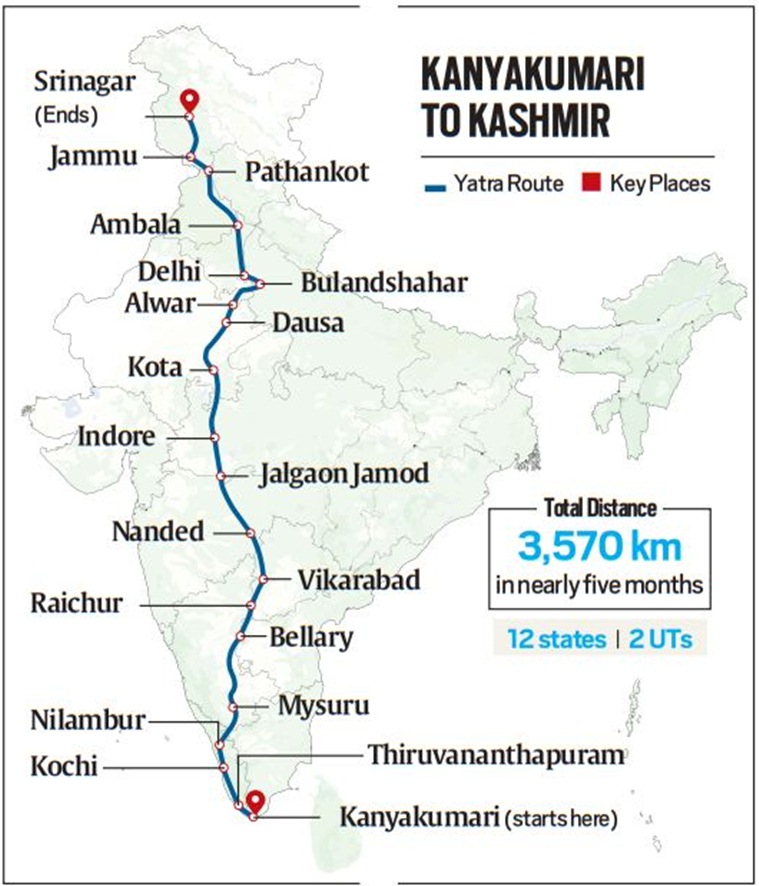

The route that the yatra will cover.

The route that the yatra will cover.

In India, a yatra has at least four meanings. It is a physical “journey” where the traveller moves from one place to another. It is an internal “discovery” where causes long overlooked, both personal and public, acquire new political significance, especially when one shuts up and listens. It is a “pilgrimage” — as in the “char dham” yatra — when the pilgrim travels to different hallowed sites to receive blessings from the people. And it is a “signal” of change that another India is possible. To succeed, the Bharat Jodo Yatra will have to be all four things simultaneously.

Peter Ronald deSouza is the DD Kosambi Visiting Professor at Goa University. He has recently co-edited the book Companion to Indian Democracy: Resilience, Fragility and Ambivalence, Routledge, 2022. Views are personal