It feels like the end of the world. We deserve a little treat.

Gen Z is coping through the little treat culture. These tiny hits of dopamine keep up the hypernormalisation in these times of chaos and uncertainty.

The Lababu-matcha-treat trend speaks to the chaos of our times. (Photo credits: Instagram/Labubu Shop/Canva)

The Lababu-matcha-treat trend speaks to the chaos of our times. (Photo credits: Instagram/Labubu Shop/Canva)The world may not have ended, but it’s certainly coming apart at the edges. Every headline feels like a countdown: the planet’s on fire, AI is advancing, democracies are slipping, and to top it all, everything costs more and is worth less.

Everyone I know feels it — that creeping sense that the party’s over, so we might as well just pack it up. The feeling festers as we consume half-baked dystopian headlines and lose ourselves in scrolling-induced apathy. In this fever dream, my feed alternates between get-ready-with-me videos, footage from a war-torn country, and absurd AI-generated slop.

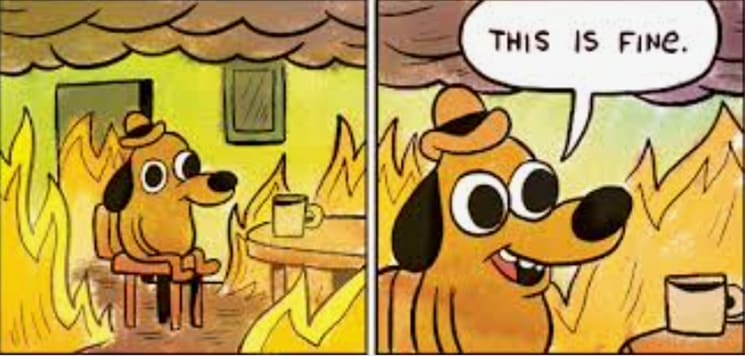

These are what we call hypernormal times — where a critical event might inspire feelings of worry and defeat, but a simple scroll can snap you out of it just as quickly. We go about our lives despite the painful awareness of our broken world. And so, with our backs against the wall and the end of the world inching closer, we choose to arm ourselves with the sweetest ammunition there is. What else is there to do but get yourself a little treat?

The little treat trend reflection of the cultural times (and algorithms)

The little treat trend reflection of the cultural times (and algorithms)Behind the ‘little treat culture’

‘Hypernormalisation’ was recently brought to the spotlight by digital anthropologist Rahaf Harfoush, who credited its origins to Alexei Yurchak, an anthropologist who used it to describe the atmosphere in Soviet Russia during the 1970s-80s. The concept, also adopted as a BBC documentary by British filmmaker Adam Curtis, suggests that when institutions fail and people in power carry on normally, the rest of us follow suit, maintaining the status quo and the illusion.

This distraction and despair make us feel like we are past the point of no return. And so, despite most conversations having a dull sense of doom colouring them, we just go right back to our daily lives. There’s a general desensitisation towards the real world — almost like we are too far removed to touch it, and our collective consciousness has been rewired to just quickly patch up any real emotion with an easier bait and switch.

In the age of hypernormalisation, we go about our lives despite the painful awareness of our broken world. (Screenshot)

In the age of hypernormalisation, we go about our lives despite the painful awareness of our broken world. (Screenshot)When I read about this, my relief at finally finding the correct words to describe the feeling was quickly overcome with the uneasy thought that so many of us felt the same way that it warranted an explanation. Unable to sit with the feeling any longer, I texted my friend to go have a coffee, to which she quickly replied, “A little treat for us.”

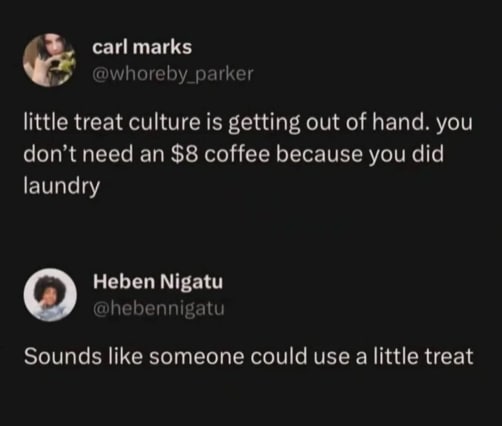

Little treat culture, the internet will tell you, is all about rediscovering joy in everyday life. Have you had a terrible day? A difficult appointment? Or successfully got through your to-do list? You may now indulge in a small treat.

The trend initially wasn’t all about purchasing treats but rather focusing on taking a break and living more intentionally, or any form of self-care that speaks to you. But in true internet fashion, the current trend looks a lot like an extra-large coffee, a baked goodie, a lip gloss, or a new plushie.

When we reward ourselves, the brain obliges, and we get our release of dopamine. Funny enough, the anticipation of joy is enough to trigger its release as well. That fleeting moment — a psychological carrot waiting for us — keeps us hooked. In this daily ritual of ‘dopamine dosing’, we are only refining the ancient mechanism of self-motivation. We humans have always required reinforcement to propel forward.

Uncertainty fuels treatonomics

The ‘little treat’ trend has catapulted itself into our vocabulary and has become a reflection of the cultural times (and algorithms). Naturally, when everything is amplified through a screen but never real or tactile, these little treats have a way of grounding us. If we are in the cycle of grief, I am afraid we are stuck at bargaining, hoping for a trade-off to cope with an unknowable and uncertain future.

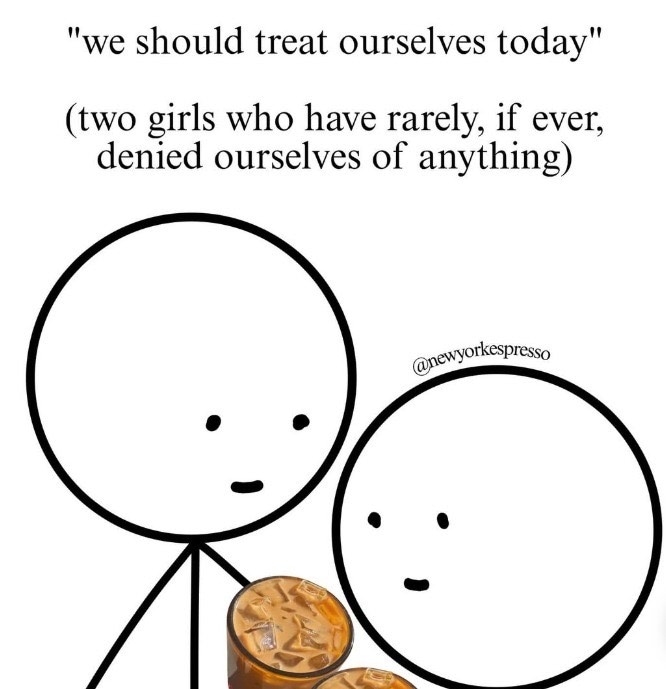

For Gen Zers, this uncertainty also stems from economic and job market troubles that have taken away their financial security. In an increasingly chaotic world, the hyper-luxuries one may dream of seem to be moving further out of reach. My generation has taken it upon ourselves to instead indulge in what makes us “feel” luxurious instead.

The little treat trend was initially about self-care, but it has quickly transformed into an extra-large coffee or a new plushie. (Screenshot)

The little treat trend was initially about self-care, but it has quickly transformed into an extra-large coffee or a new plushie. (Screenshot)

Leading the ‘Treatonomics’ trend was the Labubu — far from just a collector’s cause, it was a gold rush of its own kind. A Labubu doll is in no way synonymous with the luxurious aftertaste of an expensive purchase, but it fills our cup of excitement, novelty, and community.

The Labubu and matcha craze hit jointly, and soon became more about the lifestyle signalling than the products themselves. For a lot of modern trends, the desire for the product is detached from its utility. The Labubu had the silliness and nostalgia going for it, while matcha was selling a daily ritual, gratification through experience.

This phenomenon mirrors ‘The Lipstick Index’, popularised by Leonard Lauder of Estée Lauder, suggesting that in times of economic uncertainty, people may not make big purchases but still go for mood-bursting, inexpensive items like lipstick. The lipstick may not be expensive, but it can make you feel that way.

Chasing affordable affluence

The root of our discomfort, however, may originate from the slow realisation in times like these that greater reward doesn’t always come from greater effort. When predictable paths to progress go out the window (for example, unemployment despite a college degree), we seek comfort in simpler, easily obtainable things.

In the UK, younger generations are talking about “milestone anxiety”. The timelines of the traditional stages our parents followed no longer fit. Instead, Gen Z is redefining what fulfilment looks like for them: walking out of an unhappy job, micro-retirement, and a stronger work-life balance.

When the systems we trusted to deliver stability start to wobble, the urge to seek control elsewhere becomes irresistible. In a speculative economy, any hint of predictability can feel like comfort.

The Labubu-matcha-treat trend rides this wave with precision. Companies like Pop Mart wasted no time capitalising on this reflex. It cracked the code: it promised us a treat, but with the thrill of a gamble. The success of the Labubu is partly because of its blind-box mechanism, where, until you unbox it, you don’t know which of its many avatars you have acquired. They keep the dopamine loop intact through limited drops, celebrity endorsements, and community building.

A recent PwC report also notes a pivot towards “affordable affluence” — where hyped-up, trendy items can provide “social currency”. We are a generation used to projecting our identities through careful curation. Our consumption has become a means to obtain not only psychological equilibrium but also to signal our identities and find community. And despite these hypernormal times, we are living exceedingly sheltered lives, causing cognitive dissonance. These tendencies are only fuelled by Big Tech’s rapid advancements to create frictionless experiences —the “social trend to shelf” timeline is also accelerated by delivery apps, which get us whatever we want in under 10 minutes (It’s never really 10 minutes, is it?).

This strain of desire for treats disperses the serious doom, making room for cheaper solutions to symptoms, never the problem itself. It invokes momentary happiness, one that we keep chasing through a series of similar, treat-induced highs, hoping their cumulative effect pays off. The stakes of indulgence are low, the joy immediate, and the commitment minimal.

A sign of the times — my friend sends me this image on the day I write this essay.

Let’s get a little treat — shall we? (Screenshot)

Let’s get a little treat — shall we? (Screenshot)

So for now, we brace for the next wave of news and signals, but rest assured, if it all becomes too much, we could always go get a little treat later.

The writer works in Behavioural Science and enjoys exploring how technology and human behaviour shape one another.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05