Five or Six Mangoes: How does one remember a tree without fruit?

How does one remember a tree without fruit? Aamer pallab — that beautiful phrase for the collective of mango leaves; our mango tree became its supplier in the neighbourhood.

In our old house in Siliguri’s Ashrampara was a mango tree. It was the first fruit tree that I encountered as a child.

In our old house in Siliguri’s Ashrampara was a mango tree. It was the first fruit tree that I encountered as a child.

The mango — and not the apple — was the first fruit I learnt to draw. The apple, with dimpled scalp and a perfect roundness in drawing books, sat like a statue, without any fear of being moved. The mango was unstable — it couldn’t stand without support, preferring to recline instead. And yet we drew it standing, an imaginary position, one of the first choices made by a child’s imagination. The truth is that I did not learn to draw a mango first. I learnt how to write it. The Bangla numeral for 5 resembles a child’s drawing of a mango — ৫.

My mother tells me that I’d leave the mouth of the ৫ open. It harassed her, because without the “lid”, 5 became 6 in Bangla ৬ — just the opposite of the sequence of its closing in English, where a tiny arc closes the mouth of 5 to turn it into 6. Why did I do this? my mother would ask. It turned out that I was looking for the stone — the seed — of the mango inside the ৫.

In our old house in Siliguri’s Ashrampara — the house that continues to appear in my dreams, even when the people in them are those who have never seen the house — was a mango tree. It was the first fruit tree that I encountered as a child. There were jackfruit and plum and coconut and Indian gooseberry trees in our neighbours’ backyards, and a few houses away, in Baruadadu’s plot of land, a majestic and slightly self-obsessed jaam tree whose fruit, splattered from falling around it, had turned the soil violet. My playmates and I competed not with each other but with birds for its fruits. It was a game — the person whose tongue was stained the darkest purple returned feeling superior from the playground.

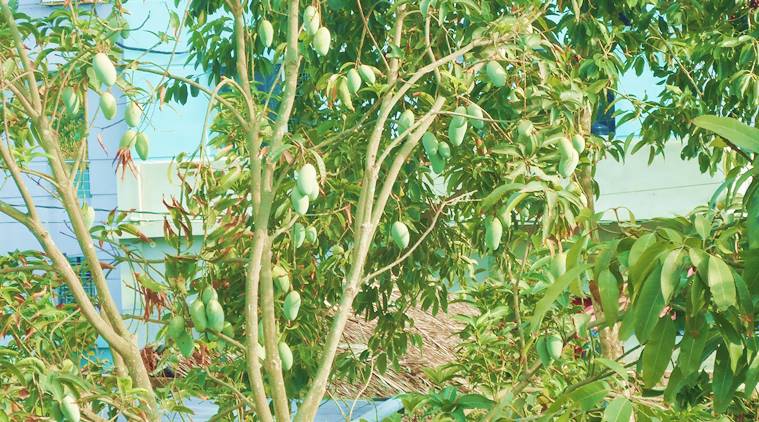

Our mango tree was its opposite. Skinny, the way the aged lose fat and flesh, but strong, it hadn’t stopped growing, piercing the air above it a little every day, so that its head, the youngest part of its body, moved like the neighbouring coconut tree in the wind. We saw its flowers after every spring — my mother noticed its mukul every day, the pale green clots that she hoped would distil the sweetness of spring and summer light into its flesh. But every year there would be a nor’wester — its giant breath would cause all the mango flowers to fall, like a bully blowing on a shy child’s birthday candles. “Next year,” my mother would say, in the tone of the schoolteacher she was, as if consoling a child repeating a class.

My playmates mocked it. They gave it new names — a footballer who’d failed to score a goal the entire season, an opener who’d had a bad run, even a classmate who’d failed class. Perhaps, because it had failed to fulfill what had been ascribed as its primary function, it performed other tasks. It was the Buri, the old woman we would have to touch to save ourselves during a game of chasing and catching each other; it held one end of my mother’s clothes-string; it was a rough and resistant board to our chalk drawings; it offered restful support to the pumpkin stems that, boneless, failed to keep themselves erect. And when my grandmother would visit us, every Thursday morning, a stem with a whorl of five leaves — sometimes seven, just in case a hand-like stem with five finger-leaves wasn’t found — would be pulled and plucked from the tree: it would be washed and tucked into a brass urn. No puja would be complete without such an arrangement. Aamer pallab — that beautiful phrase for the collective of mango leaves; our mango tree became its supplier in the neighbourhood.

It was a member of our family, the way fans and furniture are — only, it lived outside the house. And, as in our relationship with our family, we barely noticed it. We took it for a wall that, in spite of dampness and insects, survives corrosion. I see all of this only in retrospect, how we paid its health no attention — whoever thinks of the health of treesWhen we wanted a swing, my father hung a rope from a branch and my mother put an old towel on it — our excitement, and the penumbra of sounds that accompanied it, did not allow us to register the pain we were causing it. Pain is, in any case, subsonic. So when Bappa — whom the neighbourhood called “mota”, to distinguish him from the other Bappa, who was called “matha-mota”, fathead — sat on the swing, his legs, which he’d expected to go up in the air, landed cruelly on the ground. The branch broke. Angry with the mango tree for not keeping what he had thought was a natural promise, Bappa, insulted by it, kicked its trunk with his little feet. Aged bark, rough, bristly, unpleasant, fell on him, as dust, and in pieces. We waited for this strange battle to reach a climax, for some kind of retaliation from either side.

Apart from my mother’s mumbling about bad behaviour, there were no sounds. Only my brother asked Debu, then his closest companion, in a whisper, whether the mango tree had behaved badly, too.

Then, in 1987, a year after Bappa’s fall, and a year before my father would sell this house — already old when he’d bought it, with batik-like cracks on its red floors, a florescence of mushrooms and toadstools on its large wooden trellis-structured gate that we scraped with our nails — the mango tree surprised us.

The names didn’t matter to us, though I heard my parents argue about lyangra and himsagar as if they were East Bengal and Mohun Bagan. Its sweetness — as natural a piece of knowledge as the saltiness of blood — hypnotised us as its smell did flies, I suppose. But what I remember loving most about mangoes was the easy availability of the magic of life that it offered as a possibility — I could eat a mango and plant its seed immediately. I couldn’t plant chicken bones and expect a chicken to rise out of the ground. No other thing that I’d eaten had offered me such proximity to an afterlife of a living thing.

In that summer of 1987, just after our annual examination report cards had been distributed and I found myself imagining what Class VII would be like and whether the crow that sat outside the window in my classroom would appear outside the new one, the mango tree produced a mango, what was, for us, its first ever mango. A tiny mango, cryptic and self-contained in its smallness, for it showed no sign of growing or yellowing. Ajay Sir, who taught us English, compared it to the last leaf in O’ Henry’s story, my mother to a statue that’d come to life. All of us looked at it with affection, not greed. Everyone except Bappa, who said he’d have a go at it with his slingshot.

No one still knows what happened to the tiny mango. Had we all imagined it.

I looked askance at the mango tree yesterday. The gate was locked. The new owners, who spend most of the year in Darjeeling, were not there. I didn’t want to be caught staring at it. It seemed shorter now, the way humans shrink too, as if it were part of the journey towards gravity, to the soil of the earth.

I wasn’t wearing my glasses, but I thought I saw a tiny mango hanging from a low branch. As if to be sure that I hadn’t seen wrong, I checked inside my cloth bag — inside were kancha-meetha mangoes that I’d bought to have with kasundi and green chillies. Six of them.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05