Explained: The method to Turkey’s mad shootdown of a Russian jet

Turkish air force F16 jets shot down a Russian Su24 bomber 3 km inside Syrian territory after it had travelled, by Istanbul’s own official account, for less than seven seconds over Turkish territory.

Turkey shot down a Russian warplane Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2015, claiming it had violated Turkish airspace and ignored repeated warnings. Russia denied that the plane crossed the Syrian border into Turkish skies. (AP Photo)

Turkey shot down a Russian warplane Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2015, claiming it had violated Turkish airspace and ignored repeated warnings. Russia denied that the plane crossed the Syrian border into Turkish skies. (AP Photo)

Late in the night of February 21, Turkish troops launched what must rank among the most bizarre missions in military history: to remove the remains of man who had died 779 years ago. Five hundred troops, backed by tanks, tore into Syria to snatch the mausoleum of the medieval warlord Shah Suleiman, the grandfather of the first Uthmanid emperor Osman Gazi ben Ertugrul, and bring it back to safe ground.

Tuesday saw Turkey’s second military incursion into Syria — and to many around the world, it seemed just as bizarre.

Turkish air force F16 jets shot down a Russian Su24 bomber 3 km inside Syrian territory after it had travelled, by Istanbul’s own official account, for less than seven seconds over Turkish territory.

[related-post]

Furious Russian leaders have warned the incident — the first direct confrontation between a North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) member and Russia since a US U2 spy plane was shot down by the Soviet Union in 1960 — could lead to escalation.

Though world leaders are calling for calm, knowing a war between the two nuclear-armed blocs might end in apocalypse, there’s a method to Turkey’s apparent madness. Precipitating a wider crisis will draw NATO in on Istanbul’s side, giving Turkey an outside chance of saving jihadist proxies it believes could still let it reshape the region.

Though world leaders are calling for calm, knowing a war between the two nuclear-armed blocs might end in apocalypse, there’s a method to Turkey’s apparent madness. Precipitating a wider crisis will draw NATO in on Istanbul’s side, giving Turkey an outside chance of saving jihadist proxies it believes could still let it reshape the region.

Ever since the Paris massacre earlier this month, the global consensus has moved away from Turkey’s claim that handing power to the Syrian Islamists it backs is the sole way of fighting against an even bigger evil, the Islamic State. France, and even the US, seem prepared to tolerate a dispensation that includes President Bashar al-Assad — even if that means allowing Turkish proxies to be bombed.

The ghost of Shah Suleiman has, though, seized Turkish policy for years — and Istanbul isn’t ready to have it exorcised just yet.

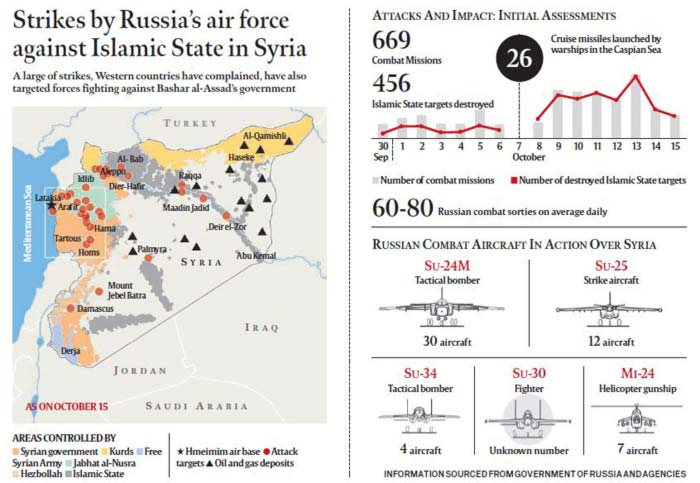

Ever since Russia began its military campaign in Syria, its airstrikes have helped the country’s military push north through the province of Latakia, to the Zahia heights, a strategic mountain complex just kilometres from the Turkish border. Helped by thousands of troops from the Iranian-backed group Hezbollah, the Syrian government has also taken control of Jisr al-Shughour, which had fallen to jihadists in April.

The advances threaten the annihilation of pro-Turkish jihadists — the welter of so-called “moderate-Islamist” militia grouped together into the Free Syrian Army.

From early in the Russian campaign, which began on September 30, Turkey began complaining that bombs were hitting Turkmen villages — a community that lives within Syria, but is allied by ties of ethnicity and language to its northern neighbour. Thousands of civilians fled the area along the border, giving credence to these claims.

This month, Turkey warned that it would shoot down Russian warjets that strayed into its territory — but few took the threat seriously, and the crisis seemed to have been defused after Moscow apologised, saying that the incidents had been the result of navigation errors.

The story was, however, more complex than it seemed. Some 10,000 Turkmen are serving in anti-regime militia, most directly funded by Turkey. The most prominent ones, the Abdulhamid I Brigade, and the Fatihin Torunlari Brigade, are involved in the insurgent siege of Aleppo; the Golden Brigade battles government troops around Damascus, while the Hak Bayragi is positioned in the Islamic State’s headquarters, Raqqa.

Istanbul hoped the ethnic Turkmen jihadists would act as a counterweight to its historic adversaries, the Kurds — the big winners of Iraq’s war, after they emerged as the cutting-edge resistance to the Islamic State.

Ethnic Turkmen, though, weren’t all Turkey was worried about: the Russian offensive threatened to snatch away a much larger prize.

From 2009, when a rebellion against President Bashar al-Assad’s military-backed regime exploded in Syria’s cities, Istanbul sensed an opportunity to expand its geopolitical reach. Neo-Ottoman fantasies took a growing grip on Turkish policymakers’ imaginations, leading them to see the Arab Spring as an opportunity to rebuild the region with Istanbul at its centre — rivalling the great power blocs of the east and west.

The idea, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said, was to build a kind of born-again Ottoman Empire, in which Istanbul would “reintegrate the Balkan region, Middle East and Caucasus”.

Inside three years, Turkey’s religious-right government had succeeded in imposing an Islamist leadership on the insurgents fighting Bashar al-Assad. Like it had elsewhere in the region, Turkey looked to the Muslim Brotherhood — the key Islamist organisation across West Asia.

Brigadier Selim Idris, a lightweight, was appointed to head the unified military command set up by Syrian insurgents at a Turkish-sponsored meeting in Antalya three years ago, but two-thirds of its membership came from Islamist groups. His deputies, Abdelbasset Tawil and Abdelqader Saleh, were both Salafists, linked to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Colonel Riad al-Asaad, founder of the Free Syrian Army, and Brigadier Mustafa al-Sheikh, both secularists known for their opposition to the Muslim Brotherhood, were excluded from the meeting, with Turkish backing.

Helped by Turkish power, the Brotherhood’s leader, Riad al-Shaqfa, dominated the political body that represented the armed groups, the Syrian National Council.

The Brotherhood also set up its own fighting units: the Body for Protection of Civilians, the Tawhid Brigades, the Farouq Brigades, Ansar al-Islam, the Euphrates Shield, the Aqsa Mosque Shield.

Frequently, the organisations allied with jihadist organisations, al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate, Jabhat al-Nusra, and the powerful Harakat Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya.

From 1963 to 1968, the Brotherhood led a dogged campaign of resistance against the secularising, Arab-nationalist Ba’ath. In 1975, it sought to capitalise on protests provoked by high prices and housing shortages — setting off a cycle of violence which ended in the regime’s destruction-by-massacre of the Brotherhood in a 1980 carnage which claimed over 25,000 lives.

Liberals were left complaining, bitterly, that the Brotherhood had hijacked their revolution. The truth was that the organisation had deep networks on the ground and in the diaspora, which it leveraged with skill.

For the West, the ongoing crisis marks a moment of decision. Ever since 2009, United States and European policies in West Asia have chased after the “moderate jihadist”, a unicorn-like beast.

But now, they must choose between continuing this strange hunt or accepting that Bashar al-Assad’s often brutal but secularist regime is the best of a set of bad options.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05