In ongoing churn in AIADMK, echoes from the past and lessons for the future

The dominant narratives of Tamil politics, with its legacy of anti-Brahmin ideology, regional and linguistic (read anti-Hindi) subnationalism, make it difficult for the BJP to grow on its own in the state.

Tamil Nadu Former Chief Minister O Panneerselvam

Tamil Nadu Former Chief Minister O Panneerselvam

Nearly four months after drifting apart and triggering a change of leadership in the Tamil Nadu government, the 2 AIADMK factions, AIADMK (Amma) and AIADMK (Puratchi Thalaivi Amma), seem ready for a reunion. Leaders are reportedly negotiating terms and conditions, and there is speculation about another change of leadership in the government. At the core of the reunion talks is the status of the Sasikala family, a clan within the larger party clan. The AIADMK (Puratchi Thalaivi Amma) faction, led by former Chief Minister O Panneerselvam (OPS), seems to have made the expulsion of the Sasikala clan a precondition for the merger. Reports suggest that a majority of the MLAs, including Chief Minister Edappadi Palaniswamy and most ministers, of the AIADMK (Amma) are willing — ironically, Sasikala is the general secretary of this faction and her nephew, TTV Dhinakaran, the deputy general secretary. The AIADMK (Amma) has the support of 122 of the 134 MLAs elected on the AIADMK’s 2 leaves symbol in 2016.

Two factors may have triggered the rethink among the AIADMK factions. One, the continued public perception that the Sasikala clan is a usurper of J Jayalalithaa’s legacy; two, the hostile response of the Centre to the developments in the AIADMK. Neither faction wants an early election, but the faction in power is unsure whether its majority would last until 2021, when elections are due. The Election Commission’s decision to freeze the 2 leaves symbol ahead of the aborted R K Nagar byelection was a big blow to the official faction. The EC took this step a few weeks after the official faction had won the floor test in the Assembly with an overwhelming majority — the Commission explained that it needed time to study the claims of the rival factions, which could not be done before the byelection. The Commission then cancelled the bypoll after allegations that the candidate of the official faction, Dhinakaran, had tried to bribe voters. The accusations followed raids by the Income-Tax department on a senior Tamil Nadu minister. The official faction complained that these “motivated” decisions were made at the behest of the BJP, but received no support from the public or from other parties. The official faction now seems to have decided that it is in its interest to dump both the jailed general secretary and her deputy.

***

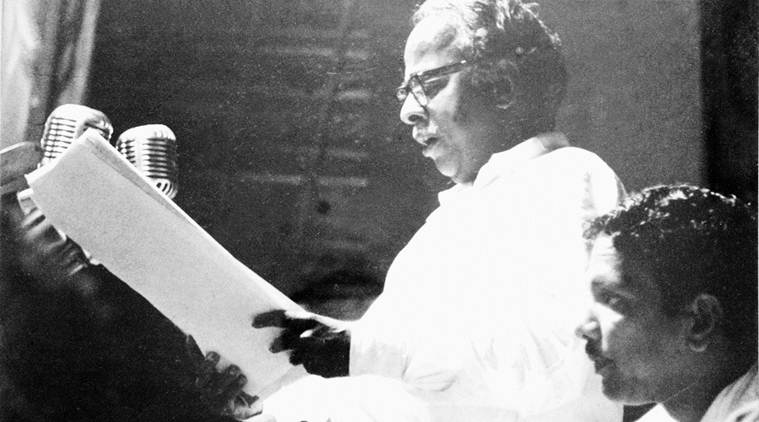

C N Annadurai seen with M Karunanidhi(PTI/Express Archives)

C N Annadurai seen with M Karunanidhi(PTI/Express Archives)

Intrigue and drama have, in fact, been a part of the history of the century-old Dravidian Movement, to which the AIADMK too traces its origin. Parricide and fratricide are par for politics, of course — the history of many political movements and parties can be written as episodes of expulsions, splits and mergers.

The first shoot of the Dravidian Movement emerged in December 1916, as the South Indian Liberal Federation (SILF). It inaugurated a paradigm of social justice politics in the Madras Presidency with its non-Brahmin manifesto that sought proportional communal representation for non-Brahmin communities. In government in the 1920s, it turned that into state policy, and laid the foundation for a truly representative government and bureaucracy. Barring occasional departures, 1916-49 was a period of consolidation for social justice politics in the region.

The SILF had, meanwhile, mutated into the Justice Party, associated with Periyar EV Ramasami’s Self Respect Movement, and transformed into the Dravida Kazhagam (DK) in 1944. By then, the politics of representation had assumed the form of a political ideology with a critical view of the caste system, and a nationalism centred on regional and linguistic identity. The Dravidian Movement also rejected Indian nationalism, and claims to an Indian nation state as represented by the national movement under the leadership of the Indian National Congress.

The first big spilt in the Dravidian Movement took place in 1949 over the DK’s approach to the new Indian nation state. Ahead of Independence, the DK stated that August 15, 1947 was “a day of mourning”, and Periyar called it “British-Bania-Brahmin Contractual Day”. C N Annadurai, Periyar’s disciple and the DK’s popular leader, disagreed: in a statement in the party organ, he declared August 15 as a “day of joy”.

Anna’s biographer, R Kannan, writes that he prepared the historic statement after discussions with his associates, V R Nedunchezhian, Sezhian, N V Natarajan and Periyar’s nephew, EVK Sampath. Periyar and Anna had started to move apart also because of the former’s decision to marry a much younger woman and anoint her as his successor. The DK split over the nationalism question, and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) emerged under Anna to use electoral democracy to further the goal of social justice and Tamil identity.

***

The DMK had its first hiccup in 1961, when Sampath and his associates, among them the popular lyricist Kannadasan, rebelled against Anna and left the party. Sampath had raised the issue of Anna giving undue importance to filmstars in the party, and argued against the DMK’s demand for an independent Dravidian nation. The split did not dent the DMK — Anna led the party to power in the state in the 1967 election. Fifty years on, Tamil Nadu has always had a government led by parties that claim the legacy of Periyar and Anna.

The next big split in the DMK came after screen idol and the party’s chief campaigner, M G Ramachandran, took on Anna’s successor, M Karunanidhi. In 1972, MGR formed the Anna DMK, later All India Anna DMK or AIADMK. The AIADMK too claimed Anna’s legacy, but the party was essentially built around the cult of MGR — with his fan clubs providing the cadres.

MGR successfully petitioned Indira Gandhi during the Emergency to dismiss the DMK government for corruption. Nedunchezhian, a close aide of Anna, too had walked out of the DMK in this period, first floating Makkal DMK and thereafter joining the AIADMK. He remained the respected Number 2 in the ministries of both MGR and Jayalalithaa until his death in 2000.

***

M G Ramachandran, seen with his protege J Jayalalithaa

M G Ramachandran, seen with his protege J Jayalalithaa

In the AIADMK, there was no scope for rebellion — since MGR was the party. His fans ran the show, and he built up a pro-poor persona modelled on, and enriched, by carefully chosen roles in films. He ushered in a centralised, authoritarian model of governance that was complemented by a politics of patronage and welfarism. His death in December 1987 led to power struggle between his wife, Janaki Ramachandran, and protege and actress Jayalalithaa. Janaki became CM but had to resign after the party spilt, which was followed by a spell of Governor’s Rule. Following the rout of the AIADMK factions in 1989, they rejoined under the leadership of Jayalalithaa, who ran the party and government in the same way as MGR, demanding total allegiance from her followers and officials. MGR initiated the idea of the political party as cult, Jayalalithaa perfected it.

Jayalalithaa’s tenure too was marked by many expulsions and inductions, but each one was at her sole discretion. The most significant of these had to do with Sasikala, who without even being an AIADMK member, wielded enormous clout over the party and government by virtue of her closeness to Jayalalithaa. She was twice expelled from Poes Garden, Jayalaithaa’s residence, and while she did manage to get back into Jaya’s good books, her clan was kept out — which added to the public perception that the party chief saw Sasikala’s extended family as being detrimental to both the AIADMK and its government. Jaya’s choice of OPS as CM when she had to step down also encouraged the impression that he was her chosen successor, not Sasikala.

***

These perceptions have to an extent shaped the public debate about the rumble in the AIADMK. OPS has been exceptionally smart to channelise them to his advantage, while the Sasikala clan perhaps revealed its ambitions too soon. After Jaya’s death, both OPS and Sasikala employed high drama, especially at Marina where she was buried, to lay claim to her legacy. However, Sasikala’s conviction and imprisonment for corruption, the EC freeze on the 2 leaves symbol, the cancellation of the bypoll on the ground of malpractice by Dhinakaran, and the IT raids may have turned the tide against the clan. The AIADMK’s political assets are the legacy of MGR and Jayalalithaa, and the 2 leaves symbol. The Sasikala clan may be in control of the party’s economic assets, but it seems to have lost its political inheritance. Leaders of the Sasikala faction are seen as appointees of Sasikala, whereas OPS claims to be Jaya’s chosen person. Since Amma’s death, OPS has come into his own as a politician with an extraordinary sense of timing while positioning himself as a down-to-earth and accessible administrator during his tenure as CM. He recognises the futility of imitating MGR or Jayalalithaa, and has instead deployed a political language that is quasi-mystical and reverential to the party’s 2 deities. That seems to have a resonance with the public, at least for now.

There is widespread suspicion that the BJP — which sees the AIADMK as a potential ally — has a hand in the ongoing developments. The dominant narratives of Tamil politics, with its legacy of anti-Brahmin ideology, regional and linguistic (read anti-Hindi) subnationalism, make it difficult for the BJP to grow on its own in the state. The AIADMK, unlike the DMK, has been receptive to religion — Jayalalithaa was openly religious, visiting temples and making substantial offerings to Hindu shrines. An AIADMK under OPS that derives its legitimacy from Amma’s politics is the perfect ally for the BJP in the short run.

In the 1970s, the Congress, the main opposition in Tamil Nadu, had encouraged MGR to corner the DMK. MGR took the cue, supported the Emergency and won in the state during the 1977 general election with Congress support. Once he established his party, MGR dumped the Congress. The AIADMK grew in strength and won consecutive elections in the 1980s. The Congress, meanwhile, lost its position as the main opposition in the state to the DMK, and faded into irrelevance. Therein, perhaps, lies a lesson for the BJP.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05